Achieving maximum crude oil value depends on accurate evaluation

Crude oil producers can lose substantial revenues because they do not achieve maximum value from their crude oil sales. Producers, traders, and refiners must be fully aware of key issues that can influence the market and price differentials for crude oil.

Crude oil prices are affected by worldwide supply and demand, regional refining capacities and configurations, and crude composition.

It is important to understand the advantages of various crude valuation methods, which include bulk property, refining value, and distillation yield. Some methods are more appropriate than others when evaluating single crudes vs. crude blends.

Background

The price of crude oil is governed by worldwide supply and demand and is outside the control of most producers. They do control, however, how and to whom they sell their crude, and this can affect price differentials for their crude vs. marker crudes.

A producing-only company is at the mercy of crude oil markets because it is not able to process crude in its own refining system.

The value to refiners of an individual crude relative to other crudes determines long-term crude oil price differentials since refiners are the end users of crude oil. This value is often referred to as the "technical" value, a characterization that implies this value is theoretical and cannot necessarily be achieved in the marketplace.

Short-term crude oil market factors can result in prices lower than the technical value. If the technical value is not achieved in the longer term, this usually means that it was estimated incorrectly or does not take into account certain key crude oil qualities.

The technical value is also known as, perhaps more correctly, the refining value. A crude's refining value is the value a refiner expects to realize for the products, less operating costs, from processing that crude.

Subtracting the crude oil cost from the refining value gives a measure of profit or refining margin associated with processing that crude oil.

Most refiners regularly perform these calculations to provide a ranking of current margins for processing different crude oils. This information is provided to traders to assist in crude purchasing.

Differences in refinery configuration and location mean that no two refineries will achieve the same margin for a given crude oil. In major market areas such as Northwest Europe, the Mediterranean, US Gulf Coast, and Singapore, however, incremental or marginal refining capacity will tend to set crude oil price differentials just as it sets refined product prices.

It is not easy to identify marginal capacity in each region; the type of capacity changes over time. In Europe and Asia, marginal capacity is a simpler topping or topping-reforming configuration, although there is little incremental capacity of this type in Northwest Europe.

Marginal capacity for high-complexity US Gulf Coast refineries tends to be catalytic cracking. Identifying this marginal type of capacity is important in understanding the mechanisms that affect crude price differentials and estimating refining values.

Long-term refining margins for different crude oils in a price-setting refinery should be equal. At a given point in time this may not be the case.

If the margin for a particular crude is higher than for others, refiners will tend to bid up the price of that crude until the advantage is eroded. Similarly, if margins for a particular crude are lower than for others, refiners will stop buying it; its price will fall until the margin is sufficiently high to attract buyers.

New crude streams

Fully evaluating the market for a new crude oil stream and estimating its value relatively early in the field development stage is important. The expected achievable price will affect the project economics.

Market evaluation may also result in implications for capital investments. There may be a need to transport crude long distances, for example, requiring the capability to load larger tankers, which increases costs related to tanker loading facilities.

For unusual crudes, such as heavy crudes or high total acid number (TAN) crudes, early evaluation of their value and markets can be particularly important in determining if field development can progress.

If niche markets for these unusual crudes can be identified, it may be possible to achieve higher values for the crudes than those suggested by the market clearing value in the price-setting refinery.

A heavy, high-sulfur crude oil, for example, was being considered for development in the Mediterranean area. Refinery capacities and configurations were reviewed to identify those refiners most likely to process this crude. Refineries with heavy-residue upgrading capabilities and refineries producing asphalt were identified as high-potential customers.

Price relationships between the heavy, high-sulfur content crude-Souedie-and the main marker crude in the Med-Urals-were reviewed to understand the key drivers affecting differentials between regional heavy and light crude prices.

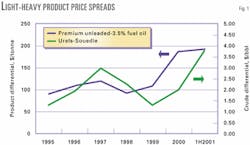

Fig. 1 shows that actual price differentials between Urals and Souedie follow the differential between light and heavy products, which is indicated by the price difference between gasoline and fuel oil.

Urals yields more light products and less fuel oil than Souedie; the movement in price differentials is therefore consistent with the refinery product yield and refining value approach.

Market volatility since 1998, however, has made it difficult for producers to adjust contract-based crude prices, such as Souedie, quickly enough to keep up with product value changes. When the light-heavy product differentials widened in 1999 and 2000, there was a lag before these differentials were fully reflected in the Urals-Souedie spread.

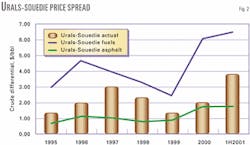

The Urals-Souedie differential also indicates that Souedie moves between its fuels-related value relative to Urals and its relative value in an asphalt-producing refinery.

Residue produced from Souedie is over 5 wt % sulfur and must be blended with low-sulfur material to produce 3.5 wt % sulfur heavy fuel oil. This results in downgraded low-sulfur material with an associated cost. Asphalt can be produced from high-sulfur residue with no associated downgrading cost, thereby eliminating the penalty for Souedie.

Fig. 2 shows actual Urals-Souedie differentials compared to predicted refining values when producing fuel oil and asphalt. Actual values lie between the predicted values. When heavier crude supplies are tighter, as they were through 1999 and early 2000 due to OPEC constraints, actual values move more closely with asphalt-based values.

The Urals-Souedie relationships were extended to a new heavy crude stream. This enabled the producer to consider a range of price differential scenarios for the crude vs. marker crudes and implied netback prices.

It also enabled the producer to assess the value of increased marketing efforts, or even a potential joint venture with asphalt-producing refineries to position the crude in this niche market.

High-TAN crude production has steadily increased in the North Sea and other areas, such as Angola. Due to metallurgy limitations and handling the highly naphthenic middle distillate produced from these crudes, many refiners can only process limited quantities. This creates a restricted market in some regions.

The producer must have a clear marketing plan and identify refiners that are able to process high-TAN crudes.

Identifying and selling crudes to refiners configured to process unusual crudes is considered a premium market compared to value obtained in a regional price-setting refinery. When production volumes are not large, producers can seek out these refiners in the premium market.

Any additional premium achieved is ultimately a function of the buyer's and seller's negotiating skills, but some mutually beneficial deal may be achieved.

Monitoring existing crude stream values

Volatility in crude oil price differentials is difficult to understand for the period since 1998. Light-heavy price spreads moved from low levels in 1998 and 1999 to the highest levels in 10 years in 2000 and early 2001.

New specifications in 2000 in Europe and the US have further complicated the market.

It is increasingly difficult for producers to understand the key factors affecting sales price differentials. It is important to understand how much crude oil price relationships are affected by crude supply changes vs. refining value changes due to product price relationships.

If a change in crude price differential results from supply changes of a particular stream, as has happened many times with Iraqi exports of Kirkuk via Ceyhan, the differential is likely to revert when normal service resumes.

If price differential changes, however, result from changes in refined product price relationships, then they may not revert quickly if driven by fundamental market changes, such as seasonality.

Fig. 3 shows that refining margins in Singapore for processing Dubai and Arabian Heavy crudes tracked each other closely through 1998 and 1999. Rapid changes in light-heavy product differentials in 2000, however, made it difficult to adjust Arabian Heavy contract prices to keep up with the market, resulting in lower margins than for Dubai.

OPEC production hit a low point at the beginning of 2000 resulting in a relatively tight heavy crude market. As OPEC production increased through 2000, the heavy crude markets weakened and Arabian Heavy margins moved back in line with Dubai by the third quarter.

It is possible to track crude values relative to one another in a range of refinery configurations using the refining value approach. Calculated crude oil differentials can be compared with actual market differentials to help understand the factors driving these differentials.

Product-price-driven effects on crude oil price differentials can then be stripped out and changes in the residual differential can be attributed to changes in crude oil supply.

Separating out the refining value change is particularly important in understanding the direction of crude oil price differentials in the recent volatile price period. Models used for tracking crude oil price differentials and refining values can be tailored to fit the producers' needs.

Blending crude oil streams

Many crude oil streams in the market are a blend of crudes from different fields. A negotiation concerning the relative value of one stream vs. others is inevitable when they differ in ownership and quality.

A producer must understand the mechanisms used to value crudes and must be comfortable that it can achieve fair value, whether blending two streams, a full pipeline quality bank, or a crude value allocation system with many inputs.

Value allocation methods

Methods commonly used in allocating value are generally the same for a simple two-crude system or a pipeline quality bank (usually referred to as a crude value allocation system in Europe). There are three widely used approaches:

- Bulk-property method. This method correlates actual crude market prices with their bulk properties to infer value. Bulk properties include: API gravity or density, sulfur content, viscosity, pour point, etc. API gravity and sulfur are widely used.

This method is relatively simple in terms of the amount of testing required and because it relates value directly to actual crude prices. It can be difficult to obtain enough reliable crude oil pricing data, covering a large enough range of crudes, to be confident enough to calculate representative bulk-property values.

Also, if there are naphthenic crudes in the blend, the quality bank system must be more complex since these crudes tend to sell for higher prices than implied by their properties.

- Refining-value method. Refinery yields and operating costs are developed for each crude stream, typically using a linear program (LP) or other model. Refinery models require detailed physical property information and distillation cuts as found in a detailed crude oil assay.

Yields and operating costs are used with appropriate product prices to calculate refining-value differentials between the crude oils.

The refining-value method simulates the process used by refiners for selecting crude oils. Detailed crude oil quality information and the need to run a refinery model to generate the yields make this method more complex than the bulk-property method.

If input-stream quality changes significantly, a new set of yields must be generated. In relatively simple systems involving only a few crudes with reasonably stable quality, the refining-value method normally provides the most accurate value allocation.

- Distillation-yield method. This is a simplified version of the refining-value method. Product yields from distilling each crude are used with product prices to calculate the relative value of each crude.

In many cases, some physical properties of the distillation cuts are used in the value-adjustment system. The quality information from each crude is relatively simple and includes distillation yields and distillation cut properties.

The distillation-yield method is more complex than the bulk-property method but less complex than the refining-value method. Because it uses product prices in the calculation, reliability of crude oil price data is not an issue.

The products being valued, however, such as naphtha, are not finished products meeting defined specifications. So, there is some uncertainty regarding the value adjustment for key properties of the distillation cuts.

Simple systems

Simple systems in which only a few crudes are blended together often use the refining-value method.

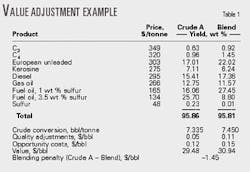

Middle East crude. A new crude with different ownership added to an existing blended stream led to the development of a Middle East system. A refinery LP model using an appropriate refinery configuration for the crude marketing region gave refinery yields and operating costs.Detailed assays provided data for the existing blend and new stream. A newly developed method calculated a value differential between the blend, with the new stream included, and the new stream itself.

The value difference was calculated monthly. Table 1 shows a simplified example. The yields were updated every 2 or 3 years to reflect the most recent stream qualities.

- North Sea crude. A new crude oil in the North Sea was to be blended with an existing stream. The existing stream's producer, an integrated multinational, proposed a value-adjustment mechanism based on a refining-value method to the new stream's producer, an upstream-only company.

The producer proposed to calculate the value differential with the refining-value method using average prices for the past year and that the differential would be fixed there for the field's life.

A review of the proposed method made clear that there was a gross error in the calculation, resulting in a $1.50/ bbl excess penalty for the new stream.

In addition, prices used in the calculation were based on a period of high light-heavy product differentials that strongly favored the lighter production stream. The new crude stream would have been penalized by almost $2/bbl.

It is not uncommon for an agreement to be reached on a fixed price differential between the owners of two streams. This represents a simple, low-administration solution.

Crude oil price differentials vary widely, as has occurred in the past few years, mainly as light-heavy differentials change. Locking in a differential can result in significant exposure if market conditions change.

Quality banks

In a more complex system, a formalized quality bank or crude value allocation system is normally put in place.

Quality bank systems are usually based on the bulk-property method or distillation-yield method. Refining-value method complexity is usually an administrative disadvantage.

There are usually a large number of parties involved in a quality bank; keeping things simple and transparent is a high priority to reach agreement between all the parties.

US systems have historically used the bulk-property method. In some cases, simple systems relying only on API gravity are used. In addition, values of bulk-property increments may stay fixed for a long time without adjusting to reflect changes in market conditions.

In the North Sea, the distillation-yield method is used in the four major pipeline systems. Some North Sea systems have been modified to reflect changes in the European refining industry.

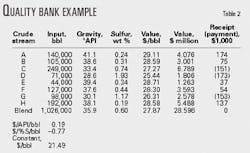

Table 2 shows a simplified example of a quality-bank calculation based on API gravity and sulfur content.

Another consideration is whether to base the settlement of value differences on a cash basis or on an equivalent volume of blended crude. Settlement on a volume basis eliminates the need for a financial transaction; the adjustment is typically made at month's end in each shipper's availabilities for the next month.

Other important factors that can affect the settlement method decision depend on where the system operates. These factors can include tax implications of financial transactions between the parties and customs issues.

Ongoing administration of the quality bank system must be well defined in an agreement that makes the exact basis for compensation clear to all parties.

Shippers normally must sign this agreement before they can ship crude through the pipeline. They need to be aware, therefore, of the likely value for their crude.

Sometimes the crude producer has alternative disposal routes. A New North field producer had the choice between routing the crude to a major North Sea pipeline system or producing the crude separately via an FPSO system.

Economics of the two options were similar, and the value achieved in the pipeline system vs. production as a segregated stream became critical to the decision.

Values were calculated for the pipeline system option using the crude value allocation procedure. An LP model gave segregated stream yields and refining values relative to Brent were then calculated.

Netback values for the segregated stream were then calculated to enable comparison with the pipeline-based values. The producer chose the segregated stream route as a result of the comparison.

The author

Colin Birch is the studies manager, industrial projects division, for Beicip-Franlab. He manages consulting activities related to markets and economics of the downstream oil and gas businesses. His area of expertise is crude oil and products pricing and markets. Birch has 23 years of experience in the downstream oil sector with Mobil and Purvin & Gertz. He holds a BSc in chemical engineering from Imperial College, London.