Indonesia's oil, gas industry faces uncertainties

Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono becomes president of Indonesia this week with the country facing a range of energy challenges.

Widhyawan Prawiraatmadja, an analyst with FACTS Inc., Honolulu, says the challenges include declining crude oil production, the country's becoming a net importer of oil products, the burden of mounting subsidies on the government's budget, declining competitiveness in LNG trade, and delays in adopting implementation rules and regulations for the 2001 oil and gas law.

Questions also loom about how the new government will deal with the section of the 2001 law dealing with opening the domestic market.

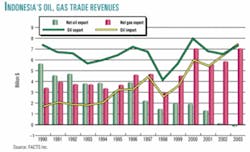

While the oil and gas industry remains important to Indonesia's economy, generating substantial government revenues, oil now has become burdensome, and gas is playing the more important role as a revenue generator, Prawiraatmadja said. By 2003, oil had become a negative trade value on a net basis, although it remained a net oil exporter in terms of volumes bought and sold (Fig. 1). This year, Indonesia probably will become a net oil importer on a volume basis.

With that new status, Indonesia will be hurt more than helped by high oil prices, and the fiscal damage will be aggravated by subsidies, which will total $6 billion this fiscal year. Subsidized prices also provide incentives for smuggling and product adulteration and hamper the development of natural gas for domestic use, FACTS said.

Inherited headaches

Because the former government did not raise Indonesian fuel prices despite high international oil prices, during the election year, Prawiraatmadja said, the new administration will have to deal with the challenge.

It is unlikely that Indonesia's domestic market prices for light products such as gasoline, kerosine, and gas oil will reflect international market prices anytime soon, and the downstream oil market will have to be opened with this constraint by yearend 2005, as mandated by the new oil and gas law.

Under this condition, the only way to attract product suppliers other than Indonesia's national oil company, Pertamina, is to adopt a regulated-margins regime similar to that applied in Malaysia, Prawiraatmadja said. This is one of many challenges for the downstream oil and gas regulator, BPH Migas, the role of which in the market opening has yet to be determined.

A final draft of implementing regulations for the 2001 law, submitted by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources to the State Secretariat for final approval, likely will be revised now that the new government is being seated. The Ministry of Energy has issued "principal licenses" to at least eight private companies, three of which are foreign firms (Royal Dutch/Shell Group, BP PLC, and Malaysia's Petronas Carigali Sdn. Bhd.). Despite still-murky regulations, therefore, there are parties interested in entering the market, Prawiraatmadja said.

Prawiraatmadja said the government would have to lure upstream oil and gas companies to invest more in Indonesia's exploration activities and increase production by enhancing the country's attractiveness through a better-managed and more-efficient energy ministry and regulator. It would also have to provide more-appropriate terms and coordinated efforts by the central and local governments to provide incentives, regulatory clarity, and safety.

Regulatory delays and lack of clarity in marketing LNG have hurt Indonesia's ability to compete with other LNG suppliers.

Improved governance

The FACTS analyst said the new government also faces the challenge of building competence in oil and gas institutions, including policymakers, regulators, and the state oil company.

The government and inexperienced downstream oil and gas regulators, unaccustomed to competition, have never issued regulations facilitating efficient and transparent market competition.

In light of Pertamina's poor image abroad, a nonpartisan political consensus is needed to support the company so it can move forward effectively without the "baggage of past sins" and without charges of political motivation, Prawiraatmadja said.