India walks pragmatic oil, gas policy line

Manish Vaid

Observer Research Foundation

New Delhi

India’s energy journey is at a critical crossroads. Evolving US-Venezuela relations underscore the risks of overdependence on a single energy source. India's ongoing oil-focused statecraft, reintegrating Venezuelan crude while diversifying imports, reflects a strategy rooted in autonomy and sustainability.

For India, energy security has always been a delicate balancing act, a tightrope walk between ensuring stable imports and navigating the complexities of global geopolitics. Recent developments under US President Donald Trump’s second term have introduced new uncertainties that threaten to disrupt this balance, forcing India to rethink its energy strategy.

Trump’s aggressive push for US shale oil dominance, coupled with his decision to withdraw the country from the Paris Agreement through the 2025 executive order “Putting America First In International Environmental Agreements,” has significantly reshaped the global energy landscape.1 These moves not only destabilize oil markets but also challenge international climate commitments, posing substantial hurdles for India’s renewable energy transition and its broader energy security goals.

Compounding these issues is the resurgence of US sanctions on Venezuela, a country historically crucial to India’s energy imports. Before sanctions were first imposed in 2019, India’s Reliance Industries Ltd (RIL). was the second largest buyer of Venezuela’s crude after China National Petroleum Corp.2 The ongoing isolation of the Maduro regime under US pressure forces India into a delicate diplomatic balancing act, continuing to rely on Venezuelan crude while simultaneously strengthening its strategic partnership with the US, particularly in clean energy cooperation. At the intersection of these geopolitical shifts, India faces a daunting array of difficulties: rising volatility in oil prices, the need for diplomatic recalibrations, and the urgency to accelerate its renewable energy transition.3

This article delves into the impact of Trump-era energy policies on India’s energy security, exploring how India is recalibrating its diplomatic strategies to maintain energy independence. It will also highlight India’s ongoing efforts to achieve a sustainable energy future. The argument put forth is clear: India must respond with agility, forging new international partnerships while navigating the complexities of an increasingly volatile energy landscape. In the face of geopolitical uncertainties, the path forward to energy security lies in resilience, innovation, and a steadfast commitment to strategic autonomy.

Historical context

By the 1990s, Venezuela had solidified its position as a key supplier of crude oil to India, providing it with a stable supply and fostering economic interdependence. This partnership symbolized India’s broader strategy: maintaining energy security while navigating the volatility of global oil markets.

The imposition of economic sanctions on Venezuela from 2005 onward, however, began to strain this relationship, complicating India’s oil procurement and driving up transaction costs. These sanctions were part of a broader geopolitical strategy that sought to isolate Venezuela but unintentionally disrupted global energy supply chains.

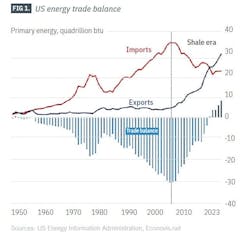

The early 21st century ushered in a new era, with the US shifting from an energy importer to a dominant exporter (Fig. 1). While this development opened new opportunities for India to source energy, it also introduced fresh complexities.

The first Trump administration’s policies targeting nations like Venezuela with sanctions further complicated India’s energy landscape, disrupting traditional supply routes and highlighting the need for greater strategic agility. Over the course of 16 years, US energy imports dropped 37% (2007–23), while exports soared 452%, transforming the energy trade balance from a 29.3-quadrillion btu deficit in 2007 to a 7.8-quadrillion btu surplus in 2023.

Diplomacy, resilience

India’s long-standing relationship with Venezuela in the oil trade epitomizes its broader energy diplomacy, which seeks to balance strategic imperatives with economic pragmatism. Over the years, Venezuela has been a key player in India’s energy strategy, supplying crude oil vital for sustaining the energy needs of its rapidly growing economy. This strong partnership, however, began to face significant challenges, particularly due to the imposition of US sanctions.

The imposition of US sanctions on Venezuela in 2019 marked a pivotal moment. Indian refiners, cautious of secondary sanctions, were forced to scale back their imports, eventually halting trade altogether. The US began to supply more hydrocarbons to India, becoming its fifth largest crude and LNG supplier.4 This shift introduced new risks, particularly as regards the political instability of the Middle East.

The landscape shifted again in 2023, when the easing of US sanctions allowed Indian refiners to cautiously reestablish trade relations with Venezuela. By October 2024, Venezuelan crude was once again flowing into Indian refineries, with Indian Oil Corp. Ltd. purchasing 1.2 million bbl and RIL resuming oil swap arrangements with Venezuela’s state-run oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA).5 These renewed engagements coincided with a resurgence in Venezuela’s oil exports, which had reached a 4-year high of nearly 950,000 b/d as of October 2024.6

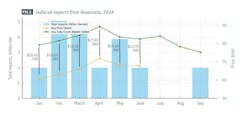

The revival of Venezuelan crude imports is not only a testament to India’s diplomatic resilience but also an economic advantage. Venezuelan crude offers a significant price benefit, with barrels averaging $15-19 cheaper than India’s typical oil import basket.7 For example, in June 2024, RIL secured Venezuelan crude at $68/bbl, $14 lower than discounted Russian crude and $20 cheaper than Saudi and US grades (Fig. 2). These savings could potentially reduce India’s annual oil import bill by $3 billion, enhancing the economic resilience of Indian refineries.

In 2024, Venezuela's crude exports averaged 705,000 b/d, the highest level since 2019. During this period, India imported approximately 22 million bbl, accounting for 1.5% of its total oil purchases. Notably, RIL brought in nearly 20 million bbl of this figure, as reported by Kpler. The return of Venezuelan crude to India’s portfolio also reduces the country’s reliance on geopolitically volatile regions, particularly the Middle East.

Sanctions and sovereignty

During Pres. Donald Trump's first term, US sanctions targeted PdVSA, aiming to dismantle Pres. Nicolás Maduro's regime by crippling Venezuela’s primary revenue stream, its crude oil exports.8 Venezuela, home to some of the world’s largest oil reserves, estimated at 303 billion bbl, experienced a dramatic contraction in oil exports.9 In 2020, under the weight of sanctions, Venezuelan exports plummeted 37.5% to just 626,534 b/d, the lowest level in 77 years.10 The revenue loss also was significant, with Venezuela losing an estimated $11 billion annually.11

For India, the sanctions posed dual problems: the immediate disruption of Venezuelan crude imports and broader volatility in oil markets. Even as Venezuelan crude exports dwindled, India, along with China, adjusted its import strategies and cautiously reengaged Venezuela following the easing of sanctions in 2023.

Trump’s policies

The first Trump administration ushered in a transformative era for US energy policy, emphasizing domestic energy dominance and retreating from multilateral climate commitments. These shifts had profound global implications, influencing oil prices, trade flows, and the strategic calculations of major energy importers, including India. Another round of the same is already underway with the start of the second term.

The withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, which became effective Nov. 4, 2020, was justified as necessary to protect American workers and industries from what the Administration viewed as unfair economic burdens.12 The move drew widespread international criticism and prompted a rollback of domestic environmental regulations, prioritizing fossil fuels over renewable energy. India found itself navigating an increasingly fragmented international landscape for clean energy funding and collaboration.

The first Administration's push for "America First" policies aimed to establish the US as the world’s leading energy producer.13 By 2019, US crude oil production exceeded 12 million b/d, positioning the country as a net energy exporter. Traditional oil producers, including Venezuela and members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), faced heightened competition from the US.

Dual realities

The new US retreat from the Paris Agreement could significantly undermine international efforts to transition toward renewable energy, including weakening key mechanisms, such as the Global Methane Pledge, which aims to reduce methane emissions by 30% from 2020 levels by 2030. For India, the US withdrawal presents dual problems. Reduced international support for clean energy could hinder progress toward India’s target of having 500 Gw of non-fossil fuel power generation in place by 2030. And India is forced to shoulder the financial and technological burdens of any progress that is to be made.

Had the US remained committed to the Paris Agreement, it could have played a pivotal role in supporting India’s clean energy ambitions. For example, the US could have facilitated access to advanced solar and wind technologies or provided critical funding through global platforms like the Green Climate Fund, attracting greater private sector investment to India’s renewable energy development and reducing the financial burden on India’s government resources.

As of December 2024, India’s renewable energy capacity had reached 209.44 Gw, year-on-year growth of 15.84%.14 But to meet the 2030 target, India must add an average of 50 Gw annually, a substantial goal that demands a combination of financial resources, technological advancements, and global partnerships.15 India continues to seek out new avenues for international collaboration, notably through partnerships with countries like Australia, and initiatives such as the International Solar Alliance.

Renewed energy synergy

Despite Pres. Trump’s emphasis on energy independence and fossil fuels, US-India collaboration continued to thrive during the first Trump Administration through initiatives like the US-India Strategic Energy Partnership (SEP), later restructured into the Strategic Clean Energy Partnership (SCEP). Established in 2018, SEP focused on enhancing energy security, expanding access, to energy, and fostering innovation.

Under Trump’s leadership, the US became a significant supplier of crude oil and LNG to India, reducing its dependence on Middle Eastern oil. By 2020, India was importing about 250,000 b/d of US-sourced crude oil.16 This partnership not only bolstered India’s energy security but also reinforced US energy markets and diversified global oil supply chains.

Looking ahead, clean energy cooperation remains viable if it aligns with both nations' economic and geopolitical interests. India’s ambitious renewable energy targets, such as achieving 500 Gw of non-fossil fuel power generation capacity by 2030, offer numerous opportunities for joint growth. The US can play a crucial role in supporting India’s green transition through technology transfer, investment, and joint research initiatives like the US-India Clean Energy Finance Task Force.17

Hydrogen’s promise

The US and India can accelerate their clean energy goals by collaborating regarding green hydrogen, a promising avenue for sustainable energy development. India has set an ambitious target of producing 5 million tonnes/year (tpy) of green hydrogen by 2030.

Green hydrogen plays a pivotal role in the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), a strategic initiative designed to enhance economic integration and clean energy development.18 IMEC plans to establish hydrogen pipelines, facilitating India’s transition to renewable energy while supporting broader geopolitical objectives. During Trump’s second term, however, green hydrogen may face resistance, as the new administration favors fossil fuels and is rolling back clean energy subsidies.

Despite these difficulties, IMEC’s potential remains compelling within the broader strategic landscape. The corridor's role in boosting trade efficiency, enhancing economic integration, and strengthening geopolitical ties makes it a valuable initiative beyond just clean energy. Framing IMEC as not only a clean energy initiative but also a geopolitical tool, positions it to remain as a cornerstone of US-India relations.

The author

Manish Vaid, a junior fellow at Observer Research Foundation, researches energy policy and geopolitics. He holds an executive post-graduate diploma in petroleum management (with a specialization in the oil and gas sector) from Pandit Deen Dayal Energy University, Gandhinagar, Gujarat.

REFERENCES

- White House, “Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements,” Presidential Actions, Executive Order, Jan. 20, 2025.

- Verna, N., “India’s Reliance gets US nod to import oil from Venezuela, source says,” Reuters, July 24, 2024.

- Fontenot, A., “A Glance at Shale Break-Even Prices Amid Declining Oil Prices, TGS, Sept. 16, 2024.

- Ghosh, A. and Srinivasan, A., “Trump or Harris—How US Election Outcomes Could Impact India’s Energy Security,” Council on Energy, Environment, and Water, Nov. 5, 2024.

- Verma, N. and Parraga, M., “Trader Vitol sells Venezuelan oil to Indian refiners, trade sources say,” Reuters, Oct. 9, 2024.

- Parraga, M. and Guanipa, M., “Venezuela’s oil exports hit a 4-year peak on higher output, sales to US, India,” Reuters, Nov. 1, 2024.

- Dinaker, S., “Crude calculations: How cheaper Venezuelan oil flows will help India,” Business Standard, Sept. 9, 2024.

- Nephew, R., “Evaluating the Trump Administration’s Approach to Sanctions: Venezuela,” Columbia SIPA, June 17, 2020.

- OPEC, “Venezuela Facts and Figures,” Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/171.htm

- Paraskova, T., “Venezuela’s 2020 Oil Exports Plunged to the Lowest Level in 77 Years,” Oil Price, Jan. 4, 2021.

- Oliveros, L., “The Impact of Financial and Oil Sanctions on the Venezuelan Economy,” Washington Office on Latin America, October 2020.

- US Department of State, “On the US Withdrawal from the Paris Agreement,” Nov. 4, 2019.

- Guliyev F., “Trump's ‘America first’ energy policy, contingency, and the reconfiguration of the global energy order,” Energy Policy, Vol. 140, Mar. 19, 2020.

- Asian News International, “India’s renewable energy capacity sees 15.84 per cent growth, reaches 209.44 GW by December 2024,” The Print, Jan. 13, 2025.

- Press Trust of India (PTI), “India adds record renewable energy capacity of about 30 Gw in 2024,” Times of India, Jan. 11, 2025.

- PTI, “India’s imports of US oil have jumped 10-fold in last few years: US Energy Secretary,” Livemint, Feb. 20, 2020.

- US Department of State, “US-India Clean Energy Finance Task Force Holds Industry Roundtable to Advance Gas-Electric Coordination Under the Flexible Resources Initiative (FRI),” Oct. 26, 2020.

- Suri, N., Ghosh, N., Taneja, K., Patil, S., and Mookherjee, P., “India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor: Towards a New Discourse in Global Connectivity,” Apr. 9, 2024, Observer Research Foundation.