Planned LNG plants must consider potential permit modifications

Julia Elizabeth Sullivan Hank Terhune

Akin Gump

Washington, DC

Steve Davis

Akin Gump

Houston

Although the US Department of Energy (DOE) has so far not modified an LNG import or export permit after issuing it, it is not explicitly prohibited from doing so and the risk of future modification of DOE permits must be carefully analyzed and addressed in contract documents regarding LNG plants and terminals.

Typical political, commercial, and regulatory risks associated with the DOE approval process for LNG liquefaction plants include:

• The ongoing political debate over LNG exports' effect on domestic energy prices. While existing studies show LNG exports will create net economic benefits (OGJ Online, May 13, 2013), the impacts are not positive for all groups, and there are strong constituencies that oppose increased exports.

DOE recently announced that it intends to update its economic studies based on more current data (OGJ, June 9, 2014, p. 26). It is unclear what impact the updated studies will have on the political debate or when they will be completed.

• Timing. The order in which DOE acts on dozens of pending applications to export LNG is critical to the project developers. Given the continued development of other large LNG export projects globally, there may be a limited window of opportunity for US companies to capture market share.

There is, moreover, a lingering concern that, at some point in the future, DOE may impose cumulative limits on the total volume of LNG that can be exported from the US to countries with no relevant free trade agreement (FTA). This concern is reinforced by DOE's May 29, 2014, announcement that the "cumulative impacts" of US LNG exports "will remain a key criterion" in future public interest determinations.1

DOE has been taking at least 24 months to act on applications to export LNG to non-FTA countries and recently adopted a policy to defer action on applications until a given project has completed the environmental review process required under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). This means project developers will invest millions of dollars to complete an environmental review with no certainty DOE will grant non-FTA export authorization.

• Regulatory risk. After it issues an export authorization, DOE has statutory authority to amend or rescind the authorization as necessary or appropriate to protect the public interest. To date, DOE has never issued a "supplemental order" to revoke an existing LNG import or export authorization. The risk, however, that DOE could issue an order requires careful consideration by project developers.

This article addresses these and other project risks, as well as DOE's general regulatory framework.

DOE's authority

Under Section 3 of the Natural Gas Act (NGA), no person may export natural gas from the US to a foreign country or import natural gas from a foreign country without first having secured authorization from DOE. DOE must approve an application to export or import gas "unless, after opportunity for hearing, it finds that the proposed exportation or importation will not be consistent with the public interest."2

Under NGA Section 3(c),3 "the exportation of natural gas to a nation with which there is in effect a free trade agreement requiring national treatment for trade in natural gas, shall be deemed to be consistent with the public interest, and applications for such importation or exportation shall be granted without modification or delay." DOE typically grants applications to export LNG to FTA countries within 4-6 weeks.

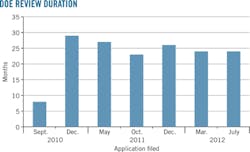

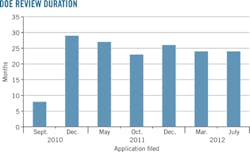

The statute creates a rebuttable presumption that LNG exports to non-FTA countries are in the public interest, and DOE must grant an application requesting authorization for such exports unless those who oppose it overcome the presumption.4 DOE has been taking about 24-30 months to act on applications for long-term authorization to export natural LNG to non-FTA countries. DOE in August 2014 adopted a new rule that will further increase the time it requires to act on some applications to export LNG to non-FTA countries.

Public-interest standard

DOE considers a range of criteria in evaluating the public interest.

Primary considerations include the domestic need for the natural gas proposed for export, the adequacy of domestic natural gas supply, and US energy security. Other considerations include the effect on the US economy, consumers, and industry, including the impact on domestic natural gas prices, job creation, US balance of trade, international (geopolitical) considerations, environmental considerations, consistency with DOE policy of promoting competition in the marketplace through free negotiation of trade arrangements, and other issues raised by commenters or interveners.5

Political and policy attention has focused increasingly on the issue of natural gas exports and, specifically, DOE's process for acting on applications to make long-term exports of LNG to non-FTA countries. Congressional representatives of various stakeholders have raised policy concerns both for and against expanded exports. Sen. Mark Begich (D-Alaska) on Mar. 6, 2014, proposed amendments to Section 3 of the NGA to expand the list of export destinations that are eligible for an expedited permitting process at the DOE. The same day Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.), chairman of the Foreign Relations Subcommittee with jurisdiction over international energy security, introduced legislation that would severely delay approval of additional exports to some destinations.6

The US House of Representatives passed subsequent legislation on June 25, 2014, by a vote of 266-150, that would expedite DOE review and approval of applications by, among other things, requiring DOE to issue a decision within 30 days following conclusion of the NEPA review. Similar legislation is pending in the Senate, though it is uncertain whether that chamber will consider the issue before adjourning later this year. These proposals, and others, highlight the continuing political interest surrounding natural gas exports.

DOE studies

DOE released two new reports on May 29, 2014, addressing the potential environmental impacts of exporting LNG to non-FTA countries (OGJ Online, May 29, 2014). The first report addresses potential environmental impacts associated with unconventional gas production in the Lower 48 states that may be induced by LNG exports.

Based on review of existing literature the report does not identify any quantifiable environmental impacts that could not be mitigated by conforming to regulatory requirements, implementing best management practices, and administering pollution prevention concepts. DOE states that it "is likely that potential impacts will be less than represented herein, as regulations and best management practices continue to improve."7 Moreover, "it is not reasonable to assume that unconventional natural gas production and the associated potential impacts will not occur if natural gas exports to non-FTA countries are prohibited."7

The second report concludes that using US LNG exports for power production in Europe and Asia will not increase GHG emissions, on a life-cycle perspective, when compared with regional coal extraction or the use of natural gas sourced from Russia and delivered to the European and Asian markets via pipeline.8

Although DOE states that it is not required to consider these potential environmental impacts under NEPA,7 it also states that the reports will be considered in its public interest determinations under Section 3 of the NGA.9 The US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit on June 6, 2014, issued an order in Delaware Riverkeeper Network v. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) that may broaden FERC's environmental review of natural gas projects, including LNG export projects.

DOE also has announced its intention to conduct updated economic studies-using more recent federal energy data-to understand how exporting up to 20 bcfd of natural gas could affect the public interest. Previous studies, analyzing lower levels of potential exports, concluded that natural gas exports would produce net economic benefits, although the economic impacts would not be positive for all groups.

Application queue

The above table shows the projects DOE has authorized to engage in long-term exports of natural gas to non-FTA countries.

As of June 17, 2014, DOE had before it 27 applications to export Lower-48 domestically produced LNG to non-FTA countries. Applications for long-term authorization to export LNG to non-FTA countries, either approved or pending as of June 17, 2014, totaled 36.02 bcfd.

Under the new rule that became effective Aug. 15, DOE will act on applications to export LNG from the Lower 48 states in the order they become ready for final action (OGJ Online, Aug. 15, 2014). An application is ready for final action when DOE has completed the pertinent NEPA review process and when DOE has sufficient information on which to base a public interest determination. DOE will use the following criteria in determining the order in which it will act on applications before it:

• Projects requiring an environmental impact statement (EIS) will be acted upon 30 days after publication of the final EIS.

• Projects for which an environmental assessment (EA) has been prepared will be acted upon following DOE's finding of no significant impact.

• Projects DOE determines to be eligible for a categorical exclusion pursuant to its regulations implementing NEPA 10 CFR 1021.410 Appendices A & B will be acted upon following this determination.

The accompanying figure shows DOE has been taking at least 2 years to act on applications to export LNG to non-FTA destinations. The processing time may be even longer under the new rule.

The lead agency for NEPA review is FERC if the LNG terminal is onshore or in state waters,10 or the US Maritime Administration within the Department of Transportation (MARAD) if the LNG terminal is offshore beyond state waters.11

Section 15 of the NGA states "For an application under Section 3 or 7 of the Natural Gas Act that requires a Federal authorization-i.e., a permit, special use authorization, certification, opinion, or other approval-from a Federal agency or officer, or State agency or officer acting pursuant to delegated Federal authority, a final decision on a request for a Federal authorization is due no later than 90 days after the Commission issues its final environmental document, unless a schedule is otherwise established by Federal law."

FERC's authority to impose a 90-day deadline on DOE has never been litigated. Assuming FERC could impose a 90-day deadline on DOE and DOE missed the deadline, the applicant could ask the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit to set "a reasonable schedule and deadline for the agency to act on remand."12 In its Aug. 15 order adopting new procedures for LNG export authorizations, DOE declined to establish a uniform deadline by which it will issue final decisions after an application's NEPA review is complete.

The practical effect of DOE's new procedures is to force project developers to commit millions of dollars and significant management resources to complete the NEPA process without any assurance that they will be able to secure the essential DOE non-FTA export authorization. DOE's new procedures may benefit projects that require only an EA rather than a full EIS because the EA projects will be able to complete the NEPA process and get their DOE permits sooner. Few projects, however, eligible to use an EA remain, and greenfield projects may now face even higher risks because they typically would require the lengthier EIS processes.

Initial reaction to the DOE rule by House Republican leaders on the Energy and Commerce Committee was negative, suggesting that the DOE proposal was expected to slow down the approval process and discourage investment in potential projects. In contrast, some key Democratic energy policy leaders in the Senate indicated initial support for the proposal.

Modification risk

DOE is authorized by Section 3(a) of the NGA, after opportunity for a hearing and for good cause shown, to make a supplemental order as necessary or appropriate to protect the public interest. DOE is also authorized by Section 16 of the NGA "to perform any and all acts and to prescribe, issue, make, amend, and rescind such orders, rules, and regulations as it may find necessary or appropriate" to carry out its responsibilities.

DOE has never issued a supplemental order to revoke an existing LNG import or export authorization based on changed economic conditions.13 A predecessor agency within DOE-the Economic Regulatory Administration (ERA)-claimed to have authority to revoke an LNG import authorization. ERA's order was appealed, but the court did not address "the nettlesome issue whether the ERA does indeed have authority to revoke a section 3 authorization, pursuant to which approximately $1 billion was invested in US facilities alone, in the absence of a violation of the terms of the authorization."

In a 1984 Policy Statement, DOE declined to revoke import authorizations although changed economic conditions were causing financial hardship for consumers of the imported gas. DOE stated that US trade policy "strongly supports contract sanctity as an important factor in international commercial transactions. Unilateral legislative or administrative action by the government to change agreements undermines this policy and the long-standing principles generally adhered to by this country in conducting trade."

DOE further held that "imports previously authorized by the ERA and FERC shall remain in full force and effect unless or until they are rescinded, amended, or superseded through appropriate regulatory proceedings. The ERA will not on its own motion initiate such proceedings unless an agreement between the United States and the government of a gas exporting country so requires."14

DOE has cited the 1984 Policy Statement in subsequent orders approving exports of Alaskan and Lower 48 gas15 and has continued to express strong support for free trade and the sanctity of contracts. In an order approving the export of Alaskan natural gas, DOE stated that "the public interest generally is best served by a free trade policy" that "promotes efficient development and consumption of energy resources, as well as lower prices."16

DOE also said that limiting exports "would send negative signals, not in the best interests of the public,...by breeding uncertainty about the reliability of the" US as a trading partner.17 There remains, however, no assurance that DOE will not exercise its power to issue supplemental orders in the future.

References

1. US Department of Energy, "A Proposed Change to the Energy Department's LNG Export Decision-Making Procedures," May 29, 2014.

2. 15 U.S.C. § 717b(a); 42 U.S.C. 7151; DOE Redelegation Order No. 00-002.04E, Apr. 29, 2011.

3. 15 U.S.C. § 717b(c).

4. Sabine Pass Liquefaction LLC, DOE Order No. 2961, May 20, 2011.

5. Presentation by John Anderson, Manager, Natural Gas Regulatory Activities, Office of Fossil Energy, US DOE, Dec. 6, 2011.

6. Freedom Through Energy Export Act, S. 2096, 113th Congress, 2014; American Natural Gas Security and Consumer Protection Act, H.R. 1189, 113th Congress, 2014.

7. US DOE, "Addendum to Environmental Review Documents Concerning Exports of Natural Gas from the United States," May 29, 2014, p. 2-3.

8. US DOE, Office of Fossil Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory, "Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Perspective on Exporting Liquefied Natural Gas from the United States," DOE/NETL-2014/1649, May 29, 2014, p. 9, 18.

9. Energy.gov, DOE LNG Exports Announcements, May 29, 2014.

10. National Environmental Policy Act, 42 U.S.C. § 4321et seq., Jan. 1, 1970.

10. Section 3(e) of the Natural Gas Act, 15 U.S.C. § 717b(e).

11. Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation Act of 2012, Pub. L. No. 112-213, § 312, 126 Stat. 1569, Dec. 20, 2012.

12. Section 19(d) of the NGA, 15 U.S.C. § 717r(d)(3).

13. Association of Businesses Advocating Tariff Equity v. Hanzlik, 779 F.2d 697, 702 n.7, D.C. Circuit Court, 1985.

14. New Policy Guidelines and Delegation Orders from Secretary of Energy to Economic Regulatory Administration and Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Relating to the Regulation of Imported Natural Gas, 49 Fed. Reg. 6,684, Feb. 22, 1984.

15. Sabine Pass Liquefaction LLC, DOE Order No. 2961, slip op. at 28, May 20, 2011.

16. Phillips Alaska Natural Gas Corp., FE Docket No. 96-99-LNG, 1999 WL 33714706, at *24, DOE, Apr. 2, 1999.

The authors

Julia Elizabeth Sullivan ([email protected]) is a partner at Akin Gump and co-chair of its energy regulation, markets, and enforcement practice. Sullivan has also served as adjunct professor at Georgetown Law Center (2001-07). She earned a BA (1985) from Texas A&M University and her JD (1988) from American University, Washington College of Law, Washington, DC. Sullivan is a member of the American Bar Association and the Energy Bar Association.

Stephen D. Davis ([email protected]) is a partner at Akin Gump with 30 years' experience. He earned a BS in chemical engineering (1979) from Louisiana State University and his JD (1981) from University of Texas School of Law.

Henry A. Terhune ([email protected]) is a partner at Akin Gump representing clients on a variety of public policy matters. Before joining Akin Gump in 1987, he was an associate staff member on the Committee on Rules, US House of Reprsentatives, working with Rep. Butler Derrick (D-SC) whom he joined in 1979. Terhune earned a BA (1980) from State University of New York-Cortland and his JD (1986) from George Washington University Law School, Washington, DC.