Transneft holds onto key transportation role, tries to ensure reliability

Russia's crude-oil pipeline company Transneft, a state-owned monopoly joint-stock company, has so far retained its key position in the transport of Russian crude oil.

Aging of the system, however, is increasingly a serious problem. And the company is using enhanced in-line inspection and new repair methods to improve system integrity and reliability.

East-west movements

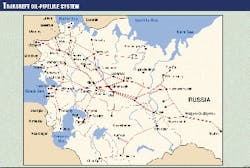

Transneft controls a vast system of crude-oil transmission pipelines throughout Russia (Fig. 1). The network transports nearly 300 million tonnes/year of oil (tpy; approximately 6 million b/d), about 99.5% of the annual Russian crude-oil production.

The Transneft network consists of more than 29,000 miles (46,800 km) of pipe, 395 pumping stations, and 868 oil-storage tanks with a total volume of 79.8 million bbl (12.7 million cu m).

The huge network of pipelines moves crude oil from central treating and storage facilities, mostly in Western Siberia's oil fields, to refineries and petrochemical plants.

In addition, this network moves oil to export terminals on the Black Sea and Baltic Sea.

When the Soviet Union disintegrated, Russia lost the essential oil ports at Ventspils, Latvia, on the Baltic Sea and Odessa, Ukraine, on the Black Sea. At present some Transneft pipelines lead not to refineries or ports, but to foreign borders.

This network of crude trunk pipelines consists of a variety of pipe sizes and capacities. The trunklines vary from 16 to 48 in. OD and include a large-diameter pipeline almost 2,900 miles long that exports oil to Western Europe.

The Ust-Balik-Kurgan-Almetievsk pipeline, 48-in. OD and 1,325 miles long, was built in 1973 to carry up to 90 million tpy (1.8 million b/d) from Samotlor oil field. But this capacity is by no means typical; some segments can move no more than 70 million tpy.

There are more than 200 river crossings and 160 miles of Urals rock segments along the pipeline route that connects Western Siberian oil fields with European Russia.

As a large holding company, Transneft incorporates at present 17 affiliates (open corporations). Among them are 11 regional pipeline operating companies, a telecommunications company, a pipeline and storage tank in-line inspection company, a pipeline design company, a pipeline river-crossing-repair company, and a pipeline insurance company.

These subsidiaries are separate legal entities with names similar to the holding company.

State control

The Transneft pipeline system currently suffers serious bottlenecks in lines moving oil to hard-currency export markets. The company intends to increase capacity at critical pipeline points and try to develop new pipeline projects.

Underlying the controversy surrounding pipeline access in Russia are the physical capacity and conditions of the pipeline system. Governmental regulations set equitable allocations of pipeline capacity for oil-producing companies to hard-currency markets.

A long-term solution of the problem of limited capacity must consider the need to upgrade and expand existing infrastructure. The company's main concern is the environmental aspect of pipeline operation, in particular the possibility of rupture and major oil spill or on-going leakage from the trunkline system.

At present, there is a lack of resources to finance major rehabilitations, upgrades, and expansions.

The Russian government retains majority shares in Transneft and maintains effective control over company activities, primarily oil exports. Transneft's oil-transportation activities fall under Russian Federal Law No. 147-FZ (Aug. 17, 1995) governing "natural" monopolies.

Governmental pipeline regulations have three targets:

- To separate oil sales and oil-transportation service.

- To provide equivalent access to pipeline transportation.

- To administer pipeline tariffs.

Basic terms of use of Russian oil pipelines were approved by the government of the Russian Federation (No. 1446) on Dec. 31, 1994. These terms encompass the export of oil and oil products beyond the customs territory of the Russian Federation after Jan. 1, 1995.

According to these terms, the system of oil pipelines shall be used to export oil, taking into account their throughput capacity and proceeding from the principle of equal access in proportion to volumes produced by individual companies.

In other words, if the export pipeline is used 100% yet incapable of satisfying total exporter demand, then the throughput capacity of this pipeline would be divided among the exporters proportional to each one's total annual oil production but not proportional to its volumes of planned export.

The Interdepartmental Commission controls the use oil pipelines and regulates issues associated with pipeline utilization. The government of the Russian Federation endorses the commission's membership.

The volumes of transported oil from each oil producer are stipulated mainly according to the volume of oil production in the quarterly schedules of transport for oil-transmission pipelines.

These schedules are approved by the Ministry of Fuel & Energy of the Russian Federation in agreement with the Interdepartmental Commission no later than 15 days before the start of each quarter. Oil producers and Transneft are duly notified.

Access to the pipeline system is crucial in any oil deal. In reality, access rights to pipeline transportation are transferred from oil producers to holding companies. There is powerful competition to use export oil pipelines, but some oil-producing companies cannot gain access to pipelines.

Payment for the services rendered by Transneft pipelines is according to tariffs approved by the Federal Energy Commission of the Russian Federation.

The Russian Federal Law on Trunk Pipelines was passed at first reading on Sept. 21, 1999, by the Russian Duma and will confirm state control over pipeline operating companies that are natural monopolies, particularly Transneft.

Oil transportation, export

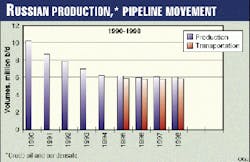

In 1998, Russia produced 304.3 million tonnes (6.1 million b/d) of oil, an increase of 6% from 1997 level. Fig. 2 presents Russian oil and condensate production for recent years. In first quarter 1999, Russia produced 74.4 million tonnes of oil, 1.5% less than production for the same period of 1998.

Since 1992, Russian oil producers have preferred to increase their hard-currency earnings by exporting oil from the former Soviet Union (FSU). Net exports to countries outside the FSU rose from 53% of produced volumes in 1992 to 89% in 1998.

Most of Russia's oil exports are destined for European customers, including Germany, France, Italy, and Spain. Oil exports (except those that pass by rail, truck, and barge) must use the Transneft pipeline network.

Total deliveries in 1998 of Russian, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan crude oil by Transneft network oil pipelines were about 296 million tonnes (5.9 million b/d), a little more than in 1997.

In 1998, Russian crude oil exports reached 135.3 million tonnes (2.7 million b/d), an increase of 9% from the 1997 level. Oil exports to outside countries that made up the FSU averaged 121 million tons (2.4 million b/d), an increase of 10% from 1997 level.

Russia has many oil fields with crude oil of different qualities. For example, Bashkirian regional oils contain sulfur from 1.3% to 4.5%, while Saratov regional oils contain sulfur only from 0.24% to 0.47%.

During transportation, various crude quality flows can mix in a pipeline and tanks and lose quality grade. Consequently, at the destination point, the customer rarely receives his specified contract shipment but is entitled to the same amount of oil of similar quality.

Technology of sequential pumping of different quality (clean and crude) oil batches was elaborated and essayed at the end of the 1970s on the Kaltasy-Ufa pipeline in Bashkiria region.

In a pipeline operation that pumps batches of different oils sequentially, the position of the respective batch heads needs to be tracked through the system. Densitomers detect changes in oil gravities, making necessary supplemental oil tanks and computerized batch-tracking programs.

Running batches of oils requires strict scheduling discipline to eliminate a large volume of oil interfacial mixture. Such technology includes:

- Determining maximum and minimum oil batch sizes and pumping cycle times.

- Planning operation and issuing schedules.

- Using computer batch-tracking programs.

- Detecting interfaces between different crude oils.

Batch-pumping technology implementation requires important upgrading of pipeline systems and resources particularly for supplemental tank construction. At present, Transneft has no resources for that upgrading and therefore usually mixes different quality oils into one grade called "Russia-Urals" that varies considerably in quality.

Transneft therefore consigns to contractors oil blends with levels of sulfur, mercaptans, or other impurities that could lower or raise the overall grade of the blend.

At the oil terminal or refinery, consignors of high-quality crude find themselves selling oil that has lost value from swilling round in pipelines with lesser blends. Consignors delivering low-grade crude into pipeline win out.

Among companies that deliver low-grade crude with high levels of sulfur is the oil production company Tatneft.

Only half of its 1998 crude production with high levels of sulfur was pumped by particular pipelines to refineries in the cities of Ufa, Samara, Nignekamsk, and Kremenchug. The other part was blended with high quality crude.

During past 5 years, Transneft has developed an oil-quality banking procedure that defines a system of financial compensation for oil-quality losses.

Producers of low-grade oils, however, particularly Baschkirian-regional oils, refuse to pay for high-quality blend after pumping.

Transneft and its clients are in dispute over an equitable oil-quality banking and compensation system. For that reason, the Russian Fuel & Energy Ministry cannot approve implementation of this oil-quality banking and compensation procedure.

Pipeline reliability

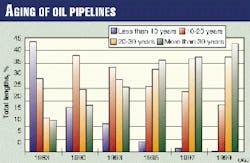

The Transneft pipeline network was developed in the 1960s and 1970s. More than 40% of the pipelines are more than 30 years old. Fig. 3 shows pipeline aging distribution.

The average age of the existing pipelines is increasing, and corrosion is an increasing concern in these pipelines.

As Transneft's pipelines age, it is increasingly important that operators be supplied with technology to inspect and assess the state of their pipelines and then rehabilitate them. .

Regulatory initiatives by the Gosgortechnadsor (the State Committee of Supervision over Russian Industry) and Goskomecology (the State Committee of Ecology) have caused pipeline operators to become more prudent in operating and maintaining their pipelines.

Transneft pipelines' safety, integrity and risk assessment, and pipeline rehabilitation programs all benefit from use of in-line and external inspection, the only method accurately to define the external and internal corrosion status of pipelines.

The increasing success of intelligent pigging, despite the cost and inherent operational difficulties, can be explained by the inherent risks to the pipeline as well as the mechanical damage to which it is subject.

Advanced in-line tools coupled with reliable interpretation of inspection data are used to evaluate the structural integrity of Transneft's oil pipelines. This evaluation now is a vital requirement for oil-pipeline operators to define necessary preventive measures and repairs required to avoid pipeline rupture or leakage.

More than 80% of the Transneft pipelines have undergone in-line inspection with intelligent pigs. Most of this inspection (about 21,000 miles) has been performed with ultrasonic pigs. Magnetic-flux-leakage pigs have been used recently.

Every year in the early 1980s, about 800 miles of oil pipelines were rehabilitated. Special machinery and about 85 crews did this rehabilitation and, if necessary, replacement.

This work was performed mainly in the ditch with the line in service. Rehabilitation involves excavation, coating removal, replacement of corroded pipeline sections, application of new coating, and quality control procedures.

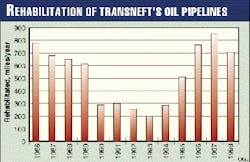

Changing economic conditions precipitated such rehabilitation dropping to 200 miles/year for oil pipelines by 1993. Fig. 4 shows rehabilitation of Russian trunk oil pipelines per year.

Beginning in 1999, rehabilitation with use of the bell-hole method and equipment has been growing.

About 54 spread and 42 bell-hole crews performed pipeline rehabilitation and replacement in 1996. Transneft has managed to create an economically effective system of pipeline rehabilitation.

Reliability of Transneft pipelines has significantly improved since the early 1990s. Pipe failures for 1990-1996 dropped from 0.27/1,000 km/year to 0.18.

The main reason was pipeline pressure and pipe-wall stress reduction caused by declining oil movements, along with in-line inspection, maintenance, repair, and rehabilitation programs.

Between pipe failures for this period, however, were isolated instances of large-volume oil spills.

For example, on Dec. 26, 1995, at the Belaya river crossing of the TON-2 oil pipeline, the underwater pipe ruptured near the city of Ufa because of mechanical failure. This pipeline had been operating 37 years; its last rehabilitation with pipe replacement was in 1972.

The river Belaya was covered with ice at that moment of pipe failure: so oil moved under the ice downstream for several kilometers. In this accident, about 1,200 tonnes of oil were spilled.

Part of this oil was recovered; the rest was burned. Cleanup of ice and river borders took more than 3 months. This work was carried out with the help of approximately 200 people, 120 machines, and various cleanup devices.

Total cost of the cleanup amounted to about 6.7 billion Russian roubles (about $1.4 million US). Total direct costs for pipeline repair was estimated at about 10.8 billion Russian roubles (about $2.3 million; conversion at the official exchange rate quoted by the Central Bank of Russia for mid-February 1996).

By 1998, improving in-line inspection and repair methods had reduced failures to 0.06/1,000 km.

Despite measures taken, however, large failures have occurred. Such a failure took place on June 13, 1999, on 334-km, 28-in. oil pipeline TON-2 in Bashkiria near the village Termenevo.

About 1,500 cu m (9,400 bbl) of oil leaked from the pipeline and 300 cu m (1,880 bbl) flowed into the rivers Uluir and Ay. The oil spill was contained, and cleanup finished by June 1999.

Because of the location, a rocky canyon of the river Ay, removal of crude oil was accomplished by burning and use of 19 river booms.

Economics

In 1996, Transneft's operating revenues from transport and storage services were more than 18.6 billion roubles earned from operations. Net income of the company was more than 5.5 billion roubles; the profitability (net income as a portion of operating revenues) was therefore about 30%.

At the same time, Transneft, as a natural monopoly, fell under the increasingly rigid control of the Russian State bodies. The Ministry of Fuel & Energy of the Russian Federation and Federal Energy Commission of the Russian Federation usually represent the interests of the oil-producing companies and political forces.

Oil-producing companies contend that the tariffs are far too high. Transneft affirms that the aging system needs large infusions of money for in-line inspection, repair, and rehabilitation of its aging pipelines.

Because of the adoption of new tariff methodologies during 1996-1998, Transneft's tariffs approved by the Federal Energy Commission of the Russian Federation increased only 4%. In 1997, Transneft's operating revenues were more than 17.6 billion roubles, but net income was only 4.3 billion roubles. Profitability, therefore, was only about 24.8%.

The currency component of the tariffs is reduced for recent years from $3.5/tonne to $1.5/tonne of exported oil in 1998. Debts of the oil producing companies to Transneft for transport services have increased.

In 1998, Transneft's operating revenues were more than 16.1 billion roubles; net incomes, more than 3.1 billion roubles. So that profitability was only about 19%.

In 1998, operating expenses decreased 12.3% over those for 1997; operating revenues decreased by about 8%.

Earlier profitability of Transneft was two to three times greater than the profitability of other oil-producing enterprises. Now, Transneft looks more like several other Russian oil and gas producing companies.

Earlier, Transneft did not use debt. Now, however, the company plans to borrow but only for construction of new oil pipelines.

Network mileage operated is shrinking, and new pipeline projects for Russian oil production have dropped for the past 10 years.

For example, at the beginning of the 1980s, annual oil production of the Samotlor field of Tumen region was more than 150 million tpy (3.0 million b/d). In 1998, Samotlor field oil production was only 16 million tpy (0.32 million b/d).

Consequently, falling oil output from producers has reduced the Transneft network for the past 3 years to only 55% of design capacity for oil transportation. Usually only part of the pipeline pumping stations operate in cases of partial charge of pipeline.

However, some pipelines, mostly for oil export, are working at full capacity; other pipelines are idle. Therefore, Transneft must idle segments, pumping stations, and storage facilities.

Such idle pipelines are usually mothballed or dismantled and removed from operation if there are no proposals from consignors to transport oil. From 1996 about 1,640 miles of pipelines and 70 pumping stations that cannot be used for export of oil have been mothballed or their facilities and equipment dismantled and removed from operation.

Lately, oil has been transported for export on Transneft oil pipelines to terminals in Novorossiysk and Tuapse on the Black Sea and to borders of Ukraine, Belarussia, and Latvia.

Pipelines to Russian terminals are full, restricting oil exports. Oil exporters prefer to use the Russian oil pipelines and terminals because those in Ukraine and Latvia levy much higher tariffs for oil export than Russia.

Transneft intends to participate in plans to build new export terminals and pipelines. The Baltic Pipeline System (BPS) should link oil fields in the Timan Pechora region to the Primorsk terminal on the Russian Baltic coast and transport at first stage 150,000 b/d.

A consortium for BPS construction includes Amoco, British Gas, Conoco, Neste, and Russian oil producing companies.

According to a Decision of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 476 of Apr. 30, 1999, financing of pipeline system in 1999 should be performed on the order of $100 million (US) by including in the tariffs the investment component of $1.37/ton of exported oil from May 1 to the end of the year.

After construction of the Baltic pipeline system, a joint-stock company will be created, 51% of which will belong to Transneft, and 49% distributed among the oil-exporting companies proportional to the level of export tariff paid by each.

The future

In the future, the exclusive rule of Transneft in oil transportation in Russia could be reduced, and Transneft's status as a "natural" monopoly lost.

According to the agreement, signed in December 1996, reorganizing the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), Russia possesses 24% of the participation in CPC, Kazakhstan 19%, and Oman 7%.

The remaining 50% is divided among American companies Chevron (15%), Mobil Oil (7.5%), and Oryx (1.75 %), the Russian-American joint venture LUKArco (12.5%), the Russian-British joint venture Rosneft-Shell Caspian Ventures (7.5%), the UK's British Gas (2%), Italy's Agip (2%), and Kazakhstan Pipeline (1.75%).

The oil pipeline will allow transportation of 28 million tpy (560,000 b/d) from Tengiz oil field (Kazakhstan) to Novorossiysk. Construction of pipeline, estimated to cost $2.236 billion, has begun and first oil should move by pipeline to tanker in 2001.

The Authors

B.V. Samoilov is a senior advisor on engineering for Sakhalin Energy Investment Co. Ltd., Moscow, a position he assumed in 1998.

Samoilov began his career in 1964 and has held numerous positions including chief of computing laboratory for the Scientific Research Institute of Automatic Control in Pipeline Construction, Moscow; senior researcher and associate professor of the Gubkin Institute of Oil & Gas; and chief of the scientific center of oil and gas transportation, National Institute of Hydrocarbons & Petrochemistry, Boumerdes, Algeria. He has also served as professor of the Gubkin Institute of Oil & Gas and department head for pipeline operating company Transnefteproduct.

Samoilov holds a Diploma Mechanical Engineer (1964) from the Ufa Petroleum Institute, Ufa, and Doctor of Science Diploma (1977) from the Gubkin Institute of Oil & Gas, Moscow.

For the past 3 years, Pavel A. Truskov has worked as a technical approvals manager at Sakhalin Energy Investment Co.'s Moscow office. He was with the gas production enterprise Sakhalinmorneftegas (Okha, Sakhalin, Russia) for 16 years after graduation in 1980 from the Far Eastern State University (Vladivostok, Russia) with a degree in oceanography. Truskov holds Doctor of Technical Science Diploma (1998) from Krylov's Institute, St-Petersburg.