Equation aids early estimation of gas field production potential

Natural gas is the world’s fastest growing fossil energy source, contributing 287 bcfd or roughly 50 million b/d of oil equivalent oil. Natural gas liquids and condensate contribute another 10.5 million b/d of liquids to the oil supply stream.

Global supply-demand of natural gas has grown a sizzling 30% in the last 10 years, and according to the latest IEA outlook is expected to further increase 50% to 425 bcfd by 2030. Over the last decade, new discoveries of natural gas have averaged 103 tcf/year; in contrast, production-depletion of existing reserves averaged 79 tcf/year.

Since 2000, 521 gas and gas-condensate fields have been discovered worldwide with reserves totaling 897 tcf.

The top 29 “fields,” with reserves varying from 265 tcf—supergiant Osman-South Yolotan (Iolotan) field in southern Turkmenistan—to 3.5 tcf, account for three-quarters of the total discoveries. Thirteen of these giant fields are offshore (Table 1).

This select list also includes five US unconventional shale gas plays—Haynesville, Marcellus, Fayetteville, Woodford, and Deep Bossier--with combined reserves of 185 tcf. Although they were not technically discovered during the 2000s, field-scale development did begin during this period.

Globally, there is a vast potential of unconventionals–tight sands gas, coalbed methane, and shale gas–waiting to be tapped. Together these represent an estimated in-place volume of nearly 12 qcf (quadrillion cu ft) worldwide versus 18.4 qcf of conventional resources discovered so far.1

Unconventionals have always been considered second-rate targets because current production technologies permit only modest recoveries on the order of 1-10%. Conventionals on the other hand have recoveries of 75% and higher.

The US is the only country that has implemented large-scale production of unconventionals. These plays provided 24 bcfd or 47% of total US gas supply and 43% of ultimate recovery as of 2006.

Production of unconventionals in the US has grown 71% in the last decade. Worldwide, unconventionals presently account for barely 9% of the total natural gas output, but their contribution is expected to grow sharply in the future.

New discoveries always require a comprehensive production evaluation before a development plan for the field can be made. The evaluation period can take 2 to 5 years or more from the time of discovery. Just 20% of the 521 new fields discovered during the 2000s are now on production.

Consequently, it is of paramount interest to have available an early estimate of the production capacity a new field discovery can put forward. This threshold is vital to supply analysts and for the design of production facilities.

The objective of this article is to develop an algorithm that would provide an early estimate of the production potential of new undeveloped gas fields. Due to the growing importance of unconventionals, the analysis looks into the feasibility of application of the algorithm-model to estimate their production capacity, also.

The model

Reserves are the foundation for determining the production capacity of any oil or gas field.

In a previous article,2 it was established for oil fields that the correlation between production potential and ultimate recoverable reserves is one of a power relationship

qmax = a.Kb (1)

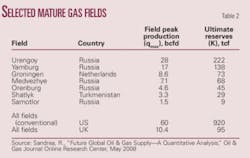

where qmax is the production capacity, K the estimated ultimate recoverable reserves (EUR), a and b are constants. This basic model was applied to a suite of seven mature giant gas fields and two countries, the US and UK, for which we have reliable data on their field peak production and ultimate reserves (Table 2). Specifically, their ultimate reserves were determined by decline analysis of their historic production data.1

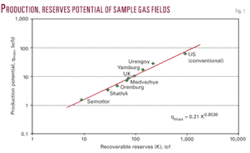

The fields were chosen to cover a wide spectrum of K-values ranging from 9 to 920 tcf. The resulting algorithm for gas fields is

qmax = 0.21 K0.8536 (2)

This has a correlation coefficient (r2) of 0.980. The units for q and K are bcfd and tcf, respectively. The correlation is shown in Fig. 1. The K-value used to determine the production capacity of a new field would normally be a volumetric estimate of its reserves.

Additionally, we analyzed the validity of the algorithm for unconventionals, which are a special case. As a new unconventional field is being developed, determination of its in-place volumes and reserves is complex because classical volumetric formulas are not applicable.

For example, current estimates3 of eventual recovery from the Barnett shale—the first of six major shale gas plays in the US to go on large-scale development—range from 35 to 50 tcf. Based on these estimates, Equation 2 establishes that the Barnett’s production potential would be between 4.4 and 5.9 bcfd. Recent published production forecasts for the Barnett assume peak values of 4.5 or 6.5 bcfd. Recent actual Barnett production is 3.8 bcfd.

The production potential model was applied to the 29 giant gas fields discovered during the 2000s. Almost all of these fields are in the development planning stage. The exceptions are Sulige, Homa, and the five US shale gas plays under development. Table 1 summarizes the published estimates of reserves for the 29 giants and their corresponding production capacities as determined by the model. Overall, the combined production potential of the 29 fields is 81 bcfd.

Final comments

A production potential model was developed to provide an early estimate of the production capacity of newly discovered gas fields.

The model is intended to be applied as soon as a wildcat is confirmed to be a gas discovery. Establishing the real potential of a gas field may take several years after discovery, following a costly appraisal drilling program.

The predictive algorithm, Equation 2, is simple and only requires a geologic approximation of the recoverable reserves of the target field at the time of discovery. It covers a wide range of field sizes and is applicable to conventional and unconventional gas fields.

References

- Sandrea, R., “Future Global Oil & Gas Supply—A Quantitative Analysis,” Oil & Gas Journal Online Research Center, May 2008.

- Sandrea, R., “Estimating new field production potential could assist in quantifying supply trends,” OGJ, May 22, 2006, p. 30.

- “Study analyzes nine US, Canada gas plays,” OGJ, Nov. 10, 2008, p. 45.

The author

Rafael Sandrea ([email protected]) is president of IPC, a Tulsa international petroleum consulting firm. He was formerly president and chief executive of ITS Servicios Tecnicos, a Caracas engineering company he founded in 1974. He has a PhD in petroleum engineering from Penn State University.

TanzaniaMaurel & Prom, Paris, and Dominion Petroleum Ltd. spudded Mihambia-1, first commitment well on the onshore Mandawa PSA in Tanzania.

The vertical well is projected to 2,300-2,800 m or Middle to Lower Jurassic.

VietnamExploratory drilling has demonstrated the existence of several hundred million barrels of oil in the Gulf of Tonkin off northernmost Vietnam, said ATI Petroleum, Oak Ridge, Tenn.

A group led by operator Petronas Carigali of Malaysia is reentering to flow test the Yen Tu-1X well, a 2004 discovery that found hydrocarbon bearing zones in two Miocene formations and the carbonate basement. It was the first oil discovery off northern Vietnam, the company said.

The group holds blocks 102 and 106 totaling 3.5 million acres off Hai Phong and has drilled the Yen Tu, Ha Long, Thai Binh, and Ham Rong wells since 2000, three of which are oil and gas field discoveries in the Song Hong basin.

The Ham Rong discovery is in 25-30 m of water on Block 106 about 75 km south of Hai Phong. Drilled to 3,700 m, it found oil in karstified carbonate basement and flowed at commercial but unspecified rates. TD is 3,700 m.

Thai Binh is a 2006 Miocene gas-condensate discovery on nearshore Block 102. It drillstem tested at 23 MMcfd in Middle Miocene at 1,200 m and 24 MMcfd in Lower Miocene at 1,600 m. TD is 2,900 m.

Other group members are PetroVietnam and Singapore Petroleum Co.

British ColumbiaImperial Oil Ltd., Calgary, began drilling the first of four planned exploration wells in the Horn River basin of northeast British Columbia in the quarter ended Dec. 31, 2008.

Imperial and ExxonMobil Canada each have 50% interest in the gas prospect. The companies hold 152,000 net acres in the area, including 16,000 acres acquired in the quarter.

AlaskaBald Eagle Energy Inc., The Woodlands, Tex., completed the acquisition of six oil and gas leases on the Alaska North Slope.

The leases, totaling 18,418 acres with 100% working interest and 78.33% net revenue interest, expire Jan. 31, 2012. The seller was not disclosed.

The leases are east of the Arctic Fortitude Unit and south of the Prudhoe Bay Unit.

KansasTeam Resources Inc., Los Angeles, purchased majority ownership in 300 miles of interstate natural gas pipelines in four counties in Kansas and Oklahoma. Seller was not disclosed.

The main line runs from Ponca City, Okla., to El Dorado, Kan. Team Resources, which has a field office in Yates Center, Kan., and plans to develop gas production in the area, will manage day-to-day operation of the system.

PennsylvaniaChief Oil & Gas LLC, private Dallas operator, expects to drill 40-45 wells and keep four to five rigs busy this year in multiple Pennsylvania counties in the Devonian Marcellus shale gas play.

The company has leased more than 500,000 acres for natural gas drilling in the Marcellus, which it noted is present from New York’s southern tier through much of Pennsylvania, Ohio’s eastern half, and through Maryland and West Virginia. In Pennsylvania, the formation extends from the Appalachian plateau into the western Valley and Ridge Province, the company noted.

West VirginiaGeoMet Inc., Houston, set a $24 million budget for 2009, down from an estimated $57 million in 2008.

Outlays include $10.1 million for Pond Creek field in West Virginia and Virginia, $7.7 million for Gurnee field in the Cahaba basin and the Garden City Chattanooga shale prospect in Alabama, and $4.8 million to the Peace River area in British Columbia.

The company expects daily net sales to grow 10-12% in 2009 from an estimated 20.4 MMcfd in 2008.