Natural gas, unconventional resources can assist India in meeting future energy demand

Gaurav Bhattacharya

University of Petroleum and Energy Studies

Derhadun, India

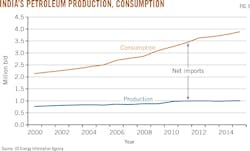

India's domestic production of crude oil is small compared to its demand. Consumption has grown 8%/year on average through 2015. Imports increased 510,000 b/d from 2010 to 2013, and further increases are expected in the coming years. Natural gas consumption increased 68% from 2005 to 2015 and has also outpaced gas production. India's energy future will likely rely on the country's untapped natural gas reserves, including shale deposits.1

India's exploration and development are uncertain following the mid-2014 drop in crude prices. Brent crude rallied to $50.05 as of Sep. 30, 2016, but growth in India's production from new sources depends on a wide range of factors.

During 2014-15 India's real gross domestic product (GDP) grew more than 6%/year. It is expected to grow at least another 7% in 2016. This growth, combined with India's increasing population, is expanding the country's energy demand. The total per capita demand now stands at 879 kw-hr, making India's total energy demand 1 trillion kw-hr.2

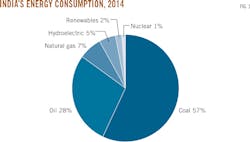

India's energy mix relies heavily on coal, oil, and natural gas. These sources will remain primary to meeting demand as the country has not made recent investments in renewable forms of energy (Fig. 1). Coal remains the largest energy source in India, but demand for petroleum and natural gas (35.5% combined) continues to increase.

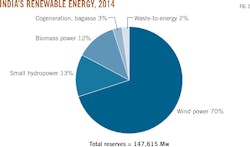

India's wind power shows potential. Wind energy harvested in Tamil Nadu accounts for 11.7% of India's entire renewable energy. The country is ranked fifth in the world in terms of exploitable hydropower, but this source supplies only 4% of the country's demand. Less than 34% of India's hydropower potential is under development. Hydropower projects, however, could supply as much as 13.9% of India's total energy demand if developed. Fig. 2 shows India's renewable energy development potential.3

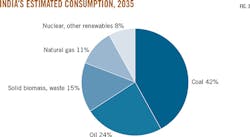

India cannot rely on renewables to meet future energy demand (Fig. 3). Renewables supply 7% of India's net energy demand. This share will only increase slightly due to the large investments required to develop renewable energy, the ease of using conventional resources, and the country's still-large coal reserves.

India consumes 3.5 million b/d of crude oil and produces only 22% of that amount. The country's refining capacity has grown by almost 20%/year since 2010. India now has the world's largest refinery at Jamnagar, Gujarat, with a capacity of 1.24 million b/d. The second largest refinery, the Paraguana refining center in Venezuela, has a capacity of 955,000 b/d.

India expects to lower its dependence on coal by 15% in the next 20 years. Crude oil use will drop by 4% in the same period. To meet the country's future demand, renewable sources would need to increase by 20% to make up for these reductions. This will not happen as renewables are projected to increase to only 8% for the same period.

Oil import dependence

India will continue to depend on imported crude as a primary energy source for the foreseeable future. Domestic exploration and production are weakened by problems with India's New Exploration Licensing Policy (NELP), the ongoing global downturn in the industry, and languishing domestic exploration.

India's government launched NELP in 1999 with the intent of awarding exploration licenses through a competitive bidding system in which national oil companies would stand on equal footing with private and foreign firms. The program has successfully increased exploration coverage of India's sedimentary basins from 11% to 52%. But only six blocks have started production in 15 years, suggesting problems finding and developing the oil.

The number of blocks awarded by India also has declined since the NELP-VI licensing round, which included blocks in India's ultra-deepwater areas (OGJ Online, Sep. 21, 2006). NELP-X awarded only 13 blocks. The shortage of bids was caused by poor exploration results over the previous 10 years and the government's failure to establish proper exploration clearance on awarded blocks from prior rounds (Fig. 4).4

Increased production in US shale formations has contributed to oversupply and lower crude oil prices. The lifting of sanctions against Iran could add further pressure to prices as the country aims to increase production by 1.5 million b/d in 2016, reaching 4.2 million b/d by yearend.

India's domestic oil production has increased 3-5%/year, due to exploration of prospective regions and introduction of directional drilling, enhanced oil recovery, and other new technologies. The country's sedimentary basins cover 1.79 million sq km onshore and in shallow water. Its deepwater area beyond the 200-m isobath accounts for 1.35 million sq km.

Only seven of India's 26 sedimentary basins are producing commercially:

• Assam-Arakhan.

• Cambay.

• Cauvery.

• Krishna-Godavari.

• Mumbai offshore.

• Rajasthan.

The offshore Mumbai basin is India's largest oil producer. These six basins make up 17% of India's total sedimentary potential. Many have matured and are now in decline. The Assam-Arakhan and Cambay basins are estimated to be the most prospective, but productive potential is low due the government's inability to provide adequate exploration clearances and the subsequent lack of interested bidders.5 The lack of viable exploration programs within India will continue to widen the gap between domestic production and energy demand (Fig. 5).

India's oil future

Even though it won't keep up with demand, India's oil production will continue to rise in absolute terms. For conventional reservoirs (2,500-3,000 m depth), the average cost of an onshore well in India is $10-$15 million. For shallow water and deepwater wells, the cost is $50-$70 million and $100-$200 million, respectively.

India's most prospective fields lie offshore in its deepwater basins. Increased investment in these fields is necessary if the country is to boost domestic oil production growth beyond 5%/year. As of 2014, 50% of the country's oil reserves (381.37 million tonnes) were offshore, with 43% in the western region and 7% in the eastern offshore area.3 Fig. 6 shows potential exploration areas both on and offshore.

Nearly 53% of India's 15 appraised and proven sedimentary basins are undeveloped. Nearly 48% of the country's sedimentary basins have yet to be appraised. Of the seven productive basins in India, at least three have further prospective acreage for exploration and development.

India's subsurface has a diverse lithology with a variety of depositional environments ranging from glaciers to deserts and lacustrine to coastal clastic and deep marine. This juxtaposition demonstrates India's potential for further exploration and development.

Natural gas demand

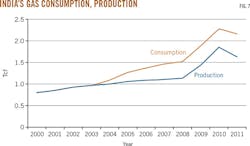

India consumed roughly 3.1 tcf of natural gas in 2015, compared to 2.3 tcf in 2010, and 1.23 tcf in 2005. Fig. 7 shows the production and consumption trends of natural gas in the past decade.

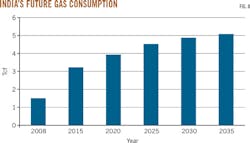

India's gas consumption outpaced domestic production after 2003 when both equaled 960 bcf of gas. The supply gap continues to widen, with demand estimated to reach 5 tcf in 2035 (Fig. 8). The country spent $306 million importing natural gas in 2015.

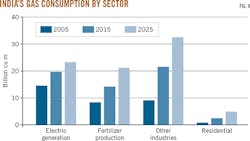

Fig. 9 shows the major sectors contributing to increased demand. Domestic and commercial power generation is expected to increase 30 billion cu m in the next decade, the same increase experienced over the last 10 years. Growth in industry consumption, notably by fertilizer plants, is expected to accelerate through 2025.

Unconventional prospects

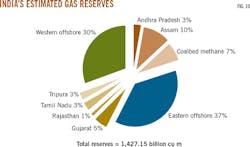

According to India's Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation, the country holds 1.42 trillion cu m (38 tcf) of conventional natural gas reserves (Fig. 10). Exploration potential for unconventional gas in shale formations and gas hydrates in India is high. The Cauvery basin shows exploration potential, and the eastern offshore and Bay of Bengal basins offer untapped reserves of gas, mainly in the form of coalbed methane off the coasts of Jharkhand and West Bengal.

Conventional resources could carry India's demand for nearly 3 decades assuming a standardized yearly production increase, but the country's shale gas reserves could last 200 years.

Shale gas

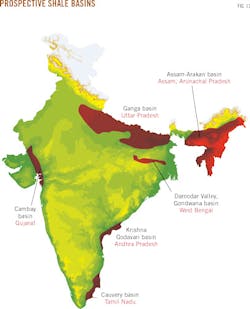

The US Energy Information Administration estimates India holds about 527 tcf of shale gas, the fourth largest shale gas reserves after China, US, and Argentina. The National Geophysical Research Institute, Hyderabad, identified 28 sedimentary basins containing shale gas in India (Fig. 11).

Unlike the US, operators in India have not experienced major success in producing shale gas. Most of India's shale prospects occur at depths of 2-5 km, which increases drilling costs. Fracing technologies exist in the country, but are not yet commercially viable due to poor implementation and the complexities of the region's shale gas basins.

The lack of a clear framework for awarding shale gas blocks has also hindered exploration and development. Most of the country's basins are in heavily populated areas, complicating development, and environmental activism has also diminished industry response. Nonetheless, the immediate need for energy may overcome these problems, leading to shale gas production by 2020.

Gas hydrates

Gas hydrates, or clathrates, are methane molecules trapped within a solid cage of ice. Gas hydrates can remain stable at about 500 m below the seafloor and occur extensively along continental shelves around the world.

India's Directorate General of Hydrocarbons launched the National Gas Hydrate Program (NGHP) in 1997 to coordinate activities related to exploration, appraisal, development, and extraction of natural gas from gas hydrates. The first NGHP expedition was carried out in 2006, with the US Geological Survey as the main technical collaborator. NGHP-1 drilled 39 wells in 21 locations, of which 16 were logged and 22 cored. The work established the presence of vast amounts of gas hydrates in India's continental shelf and river basins, most notably the Krishna-Godavari (KG) basin. India's Oil & Natural Gas Corp. Ltd. conducted a second expedition (NGHP-2) in 2015 with several technical collaborators. This project drilled 42 wells on 25 sites, and established the presence of producible gas hydrates in the deep offshore areas of the Indian Ocean and in sand reservoirs in the KG basin.6

A third expedition, NGHP-3, is scheduled to establish an efficient production plan but commercial gas-hydrate extraction technology remains in the research and development phase. India's exact gas hydrate reserves are unknown, but researchers with the National Geophysical Research Institute have estimated gas hydrates to be 1,500 times more abundant than the country's conventional gas reserves. With a 10% production rate, gas hydrates could meet India's energy needs for more than 100 years.

Coalbed methane

India contains 60.6 billion tonnes of coal. As the world's third-largest coal producer, India has potential for coalbed methan (CBM) development. According to the country's Director General of Hydrocarbons, India's major coal deposits could contain up to 4.6 trillion cu m of gas (Fig. 12).

India's CBM development has not proved successful despite the government adopting a CBM policy in July 1997. Since 2001, the government has awarded 33 CBM exploration blocks in four auction rounds yet only three of these blocks are producing.7

The lack of commercial production stems from factors including the lack of detailed reservoir characterization, the lack of professional training for domestic companies, and the lack of equipment and advanced CBM technology in the most productive basins.

References

1. Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, "Annual Statistical Bulletin," 2015, pp. 120

2. Trading Economics, "India GDP Annual Growth Rate 2015-2016," www.tradingeconomics.com.

3. Government of India, Central Statistics Office, "Energy Statistics 2015," Vol. 22, Mar. 26, 2015, pp. 1-8.

4. Inamdar, N., "NELP-X: A Primer," Business Standard, Jan. 13, 2014.

5. Dhar, D.K., Bhattacharya, S.K., "Introduction to Sedimentary Basins of India," Drilling Operations Manual, 1991, pp. 23-37.

6. Government of India, Directorate General of Hydrocarbons, "Gas Hydrates," June 2016.

7. Press Trust of India, "Govt. allows Coal India to produce gas from coal bed methane," Dec. 19, 2013.

The author

Gaurav Bhattacharya ([email protected]) is an undergraduate student at the University of Petroleum and Energy Studies, Dehradun, India. He is currently pursuing a bachelor of technology in petroleum engineering (2017). He is a member of the Society of Petroleum Engineers.