Comment: Oil and gas in energy research spending: a call for balance

This article is based on written testimony submitted by the authors in March to the US House Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Interior, and related agencies.

The US government's oil technology budget has been steadily reduced from $56.2 million in fiscal 2002 to a proposed $15 million—about 0.1% of the total US Department of Energy budget—in fiscal 2005, and the natural gas technology budget has been reduced from $44.1 million in fiscal 2002 to a proposed $26 million in fiscal 2005. The administration's proposed fiscal 2005 energy research budget is directed almost exclusively toward the long-term aspects of energy research, notably energy efficiency, renewable energy, and fuel cell and hydrogen technologies. We believe that federal energy research budgets should be more balanced and directed toward three critical time scales:

- Long-term to support higher-risk research that currently receives only limited private sector investment in areas such as renewables, nuclear, and clean coal.

- Mid-term to facilitate creation of unconventional natural gas resources to serve as a bridge to the hydrogen future.

- Near-term to facilitate the transfer of advanced oil technology developed by major oil companies to smaller independent producers to extend the slow decline of US oil production.

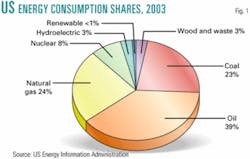

These energy research categories mimic to some degree the current US energy consumption percentages and trends for coal (23% stable); nuclear, hydro, and renewables (15% stable); natural gas (24% rising); and oil (39% falling) and represent a balanced federal approach to energy research in order to facilitate a smooth transition to a hydrogen future (Fig. 1).

Energy's impact

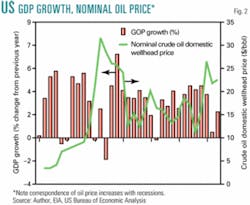

Nobel laureate Richard Smalley believes that energy tops the list of problems facing humanity today because it impacts all other major problems, including water, food, environment, poverty, war, disease, education, democracy, and population.1 Energy impacts everything that occurs in modern society. The US was built on the shoulders of reliable and affordable energy. For the past 50 years, oil has been the primary source of energy in the country, and the price of oil is closely tied to economic growth. The four US recessions in the past 35 years were each related in time to an oil price spike (Fig. 2).

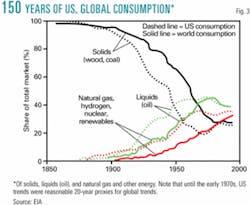

For well over a century, the global transition away from solid fuels (wood and coal) to liquid fuels (oil and natural gas liquids) to gas fuels (natural gas and hydrogen) and other energy sources (predominantly nuclear and hydroelectric) has been quite predictable and will most likely continue. As an aside, it is important to recognize that during the coming global transition away from carbon to hydrogen, industrialization will be powered largely by fossil fuels. The global energy consumption trend toward natural gas and other energy sources will most likely be good for both the economy (macroeconomic price volatility stabilization) and the environment (reduced atmospheric emissions and decreased land use).

Whereas US energy consumption trends once served as a 20-year proxy for global trends (Fig. 3), since the early 1970s US trends have run counter to global trends and shown increases in the use of coal and have been essentially flat in oil and natural gas, nuclear, and renewables (Fig. 4). The federal government has an opportunity via the strategic use of policy to help keep the US in step with global trends and support a smooth transition toward natural gas, hydrogen, and renewables. The alternative is to support policy that runs counter to global trends.

The administration's budgetary focus on long-term energy efficiency and renewable energy ($1.25 billion) and fuel cell and hydrogen technologies (approaching $500 million) is forward-looking and laudable. However, the proposed budget is dangerously out of balance in its underfunding of oil and gas research for the near and mid-term ($41 million combined). Federal energy research budgets should be directed toward the aforementioned time scales, elaborations of which follow:

- Long term (>50 years). Federal recommendations to support research and technology to investigate efficiency, and also long-term, large-scale, future sources of energy including hydrogen (from methane and other feedstock), nuclear, and solar (large-scale, improved efficiency) that will not otherwise be developed in the private sector are reasonable. Other "renewable" sources such as wind, hydrothermal, biomass, tidal, and the like will provide good supplemental regional sources but are unlikely to provide the scale of energy needed in a modern society. Although heavy investments have been made historically in such renewable energy sources, for more than 4 decades their contribution to US energy consumption has been less than 1%. Moreover, they are geographically constrained and limited in their use in the transportation sector. Nuclear and hydroelectric power plants combined currently constitute approximately 10% of US energy consumption, but because of environmental concerns, no new plants or dams have been constructed recently. Consequently, their role as a future energy source is diminishing.

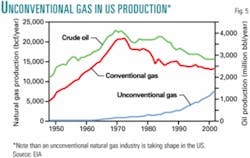

- Midterm (10-50 years). The federal government should support a smooth transition away from solid and liquid fossil fuels over the next 50 years toward other energy sources. A global natural gas industry is likely to be established during the next half-century that will serve as a bridge to the hydrogen future because natural gas represents a reasonably clean transition fuel, as well as a feedstock for hydrogen. Federal investment should include broad support for research and technology development in conventional natural gas but should expressly focus on the identification, characterization, production, and transportation of unconventional natural gas resources. The unconventional gas sources are rarely associated with oil. The unconventional natural gas industry that is being built in the US represents the natural gas future (Fig. 5).

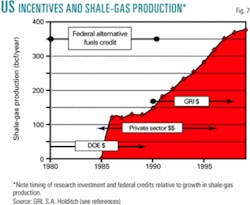

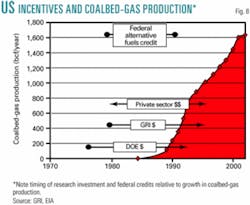

Unconventional natural gas, such as tight gas, coalbed methane, and shale gas, represents on the order of 30% of total US natural gas production today and is virtually untapped as a global resource. In the last 20 years, data show that federal and private investment in research and technology, private sector investment in exploration and development, and federal and state incentives combined to create new unconventional natural gas resources in tight formations, shale, and coal (Figs. 6-8). Complex geologic and engineering problems remain to be solved that will promote the discovery of unconventional natural gas and maximize recovery efficiency and production from unconventional resources.

This resource-creation model could be taking shape today in the deep shelf play in the shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico, where federal and state drilling incentives, combined with private and federal investments in research, technology, and exploration, could lead to the discovery of significant natural gas resources in depths ranging from 15,000 ft to 30,000 ft. In the more distant future, federal and private investments being made today in understanding and characterizing such sources as methane hydrates, very deep natural gas below-salt formations, natural gas disseminated in saltwater brines, and coal gasification could show similar results and have a significant impact on production of natural gas. Federal support should encourage private sector-university-federal partnerships and target creation and enhancement of these unconventional gas resources.

Because unconventional natural gas is often not associated with oil, it can and will be discovered and developed in places having little to no oil production, thus adding several producing countries to the more geographically limited oil production scene. This could have a stabilizing effect on energy markets and by association on economic markets (see Fig. 2 for the historical impact of volatile oil price on US gross domestic product).

A global natural gas industry requires an ability to transport natural gas. The major oil and gas companies have recognized this need, as is reflected in the number of permits for LNG terminals worldwide. US federal policy and natural gas producers large and small should support the developing LNG industry and help facilitate the industry through ease of permitting and participation in public education.

Demographic realities

Employment in the oil and gas industry in the US peaked in 1982 and has decreased steadily to a point today that is about one third of what it was at peak. The number of US oil and gas jobs lost approaches 1 million. Some of this reduction is related to the technology advancements that make scientists more efficient today than ever before, and some is related to mergers and downsizing. There is most certainly an efficiency floor to this trend.

Age demographics in the industry are perhaps more critical. More than 60% of geoscientists in the oil and gas industry today are over 45 years of age, and fewer than 18% are younger than 35.2

We are facing an interesting dilemma in the coming decade. Oil and gas companies recognize this, but have been slow to respond. Young people today are well-informed. They know where the jobs are, and they know where the federal government is investing, so it is no coincidence that enrollment in geoscience and petroleum engineering departments at universities across the US peaked in the early 1980s and has decreased by approximately 70% to a point equivalent to mid-1960s enrollments.3

For the next 50 years as we transition from a global coal and oil economy to a natural gas and hydrogen economy, it is vital that we have trained scientists and engineers in our universities because all phases of the energy business—exploration and production, environmental management, and carbon sequestration—rely on trained and educated students. Federal investment in energy research will send a critical signal to young people regarding the importance of energy research—a message that needs to resonate and that in combination with the logical floor in industry employment could help to stabilize university enrollment levels in science and engineering.

Corporate welfare

Government assistance to corporations is controversial. The words "corporate welfare" are often used in Washington, DC, as a convenient way to lobby against federal support for the oil and gas industry. The federal government supports countless industries that are critical to the general well-being of the country: banking, farming, and airlines, to name a few. We must help the informed public recognize that banks, food, transportation, and the energy that powers them are critically important to our country and that federal investment in the oil and gas industry is not only necessary but in fact wise.

Consider an energy example: the large-scale federal investment in renewable energy over the past few decades, which has been generally accepted by the voting public as an investment in "cleaner" energy. In a thoughtful presentation at a Resources for the Future conference on Jan. 21, then Under Sec. of Energy Robert Card reported that "R&D (research and development) spending in the area of renewables and energy efficiency is more than 20 times that for oil and gas."4 Important, however, is the fact that oil and gas provide 60 times the amount energy to our country than the renewable sources of wind, solar, biomass, and geothermal do combined. In other words, a federal investment of $1 in oil and gas research equates to the same energy output as $1,200 invested in renewables and has for the past 20 years. Investment in renewables and energy efficiency is warranted, but on any measurement scale—dollars invested, time to fruition, energy output, and return on federal investment—the fiscal 2005 proposed budget in oil and gas research is too low. Moreover, the investment that the federal government makes to support ongoing oil and gas research is returned via taxes and royalties at significant multipliers. Instead of "corporate welfare," perhaps it should be called a wise federal investment.

Balance, industry role

(CORRECTION: The footnote in Fig. 9 in the article "Oil and gas in energy research spending: a call for balance" contained an error (OGJ, Sept. 27, 2004, p. 22). The number for proposed federal spending on energy research in fiscal 2005 should have been $766 million.)

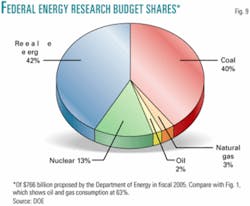

Oil and gas research programs across federal agencies have been targeted for budget cuts each year for the past several years. The administration's proposed fiscal 2005 budget for research directed at major US energy is $766 million, which represents only 3% of the total DOE budget. Of that 3%, only 2% ($15 million) is for oil, and 3% ($26 million) is for natural gas (Fig. 9). The remainder is for coal (40%; $306 million), renewables (42%; $322 million), and nuclear (13%; $100 million). Clearly, this is not a balanced approach in that oil and gas account for 63% of total US energy consumption (Fig. 1), and vital research and technology transfer remain to be done. Federal energy research budgets should be directed toward the three critical time scales described earlier.

Although the major oil and gas companies have in the past ignored, and at times even lobbied against, funding for DOE oil and gas budgets, that position needs to change and in some ways may already be changing. Informed major companies now recognize that the federal government can play a positive role in supporting students, faculty, and research scientists at universities through DOE oil and gas research budgets. Petroleum engineering and geoscience departments across the country rely on DOE oil and gas budgets to provide critical competitive funding of programs. Other federal sources, such as the National Science Foundation (NSF), do not yet fund this type of applied research. A strong federal investment in oil and gas research would send a signal to young people that energy research is important and would maintain critical federal-private-university partnerships.

The independent oil and gas community to date has played only a limited role in the oil and gas research discussion. Again, that needs to change. The production advisory groups (PAGs) for PTTC's regional lead organizations (RLOs) have made strides to become more involved in the federal discussion. Representatives of these groups visited Washington, DC, at the end of March. The message was clear. Federally supported oil and gas research and technology transfer to independents is important for the community and needs to increase, not decrease.

The road to a hydrogen future is long. Fossil energy will be prominent along that road for many decades. It is important that the US oil and gas community, from small shops to supermajors, recognize the evolving and important role of the federal government in energy research and make themselves heard in strong support.

References

1. Tinker, S. W., chair, workshop summary, National Academy of Sciences, Committee on US Natural Gas Demand and Supply Projections: A Workshop, Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2003.

2. American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Exploring member attitudes: results of a quantitative member survey, 2003.

3. American Geological Institute, 2001 report on the status of academic geoscience departments: http://www.agiweb.org/career/rsad2001.pdf.

4. Card, R., Hans Landsberg Memorial Lecture to Resources for the Future, Jan. 21, 2004.

Data sources for figures:

Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), http://www.bea.doc.gov/bea/dn/home/gdp.htm.

US Energy Information Administration (EIA), International Energy Review 2001, DOE/EIA-0219 (2001).

EIA, Annual Energy Review 2002, DOE/EIA-0384 (2002).

EIA, US crude oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids reserves: 2002 Annual Report, DOE/EIA-0216 (2002).

Gas Research Institute (GRI), GRI gas resource base: unconventional natural gas and gas composition databases, GRI-98/0364.3, digital CD-ROM.

Holditch, S.A., The increasing role of unconventional reservoirs in the future of the oil and gas business: presentation downloaded from the web site of the Society of Petroleum Engineers-Gulf Coast Section, http://www.spegcs.org/attachments/studygroups/6/Holditch2001.pdf.

Tinker, S. W., 2001, Hearing on Department of Energy Fiscal Year 2002 Budget Request, Apr. 26, 2001: House Committee on Science, Hearings for the 107th Congress 1st Session, Energy Subcommittee Hearings, http://www.house.gov/science/hearings/index.htm.

The authors

Scott W. Tinker, director of the bureau of economic geology, the University of Texas at Austin, and state geologist of Texas, holds the Allday Chair in Subsurface Geology in the university's Department of Geological Sciences. Previously, he had an 18-year career in the oil industry. He has received best paper awards from AAPG and SEPM, and has been an AAPG Distinguished Lecturer and an SPE Distinguished Lecturer. Tinker has published more than 100 books, articles, and abstracts, and given more than 150 keynote, invited, and accepted lectures. He holds a PhD in geological sciences from the University of Colorado, an MS in geological sciences from the University of Michigan, an MBA from the University of Colorado at Denver, and a BS in geology and business administration from Trinity University.

Eugene M. Kim is a research associate at the Bureau of Economic Geology. He is currently involved in oil and gas reserve growth studies, play analysis, resource assessments, economic evaluations, and geologic carbon sequestration. He holds a BSE in mineral and petroleum engineering from Seoul National University, an MA in energy and mineral resources, and a PhD in geological sciences, both from the University of Texas at Austin.