'Benign' era of refining represents greater profitability for best performers

The refining industry is entering a new "benign" era that reflects basic, permanent, structural changes in the market due to an improving global economy.

Those companies that manage their refining portfolios most effectively will prosper in the new era. They will be able to outperform their competitors in terms of market position and delivered value.

Understanding the key difficulties allows refiners to position themselves to avoid pitfalls that could derail the recovery. These will become the high-performing refiners.

During the last 20 years, the conventional wisdom has been that refining was capital intensive and low margin. The industry was trapped in a period of limited demand growth, overcapacity, and low profitability, coupled with repeated "boom-bust" cycles.

Refining is now viewed as more of a necessity than an attractive business in which to invest and grow.

It has been more than a decade since a new refinery has been built in the West; since then, refiners have focused on managing costs and operational stability and serving key local markets. Any investments are to satisfy increasingly stringent regulatory demands (low-sulfur fuels, MTBE, lead removal, etc.) that also have resulted in refinery divestments or closures.

Fundamental structural changes are now occurring in the refining industry that will end the era of low growth and low margins. These changes are due to:

Significant demand growth fuelled by broad-based economic growth.

The emergence of a global product market stimulated by changes in fuel specifications in developed countries.

Additional supplies of heavy, sour crudes will meet this rising demand, which will allow complex refiners to increase margins.

Steady growth and healthy margins will encourage additional investments. This investment will result in additional conversion capacity in many cases, particularly in the European Union where there is insufficient conversion capacity to meet product demand after 2005. This will transform the refining industry and, if managed properly, enable high-performers to outperform other companies.

Conventional wisdom

Since the early 1980s, world GDP has grown more than 40%. Refinery throughput, however, has grown at half that rate despite many more automobiles.

Installed refinery capacity has remained nearly unchanged, leaving the refining industry in an environment of slow demand growth and excess capacity. Contributing factors include:

- Large improvements in vehicle fuel efficiency, which has offset the rapidly rising numbers of vehicles, particularly in OECD countries.

- A major substitution for fuel oil by other fuels, such as natural gas, for power generation.

- A larger service economy vs. more hydrocarbon-intensive manufacturing.

The effect of these factors has been a long period of low returns for refiners. Return on average capital employed (ROACE) has been less than 10% most years and as low as 5%; this is substantially less than the "hurdle rates" that supermajors use to assess the viability of proposed investments.

Investments in refining, therefore, have fallen steadily as companies avoid all but essential investments to meet regulatory changes and focus on ongoing cost reductions.

The countercyclical nature of the upstream and downstream businesses has helped integrated oil companies (IOCs) deliver more consistent returns than independent exploration and production companies or refiners. IOCs, however, have invested most of their downstream capital in marketing; most IOCs now have more marketing than refining throughput.

Even national oil companies, eager to gain a larger share of crude oil revenue, have curtailed refining investments.

Refining has been a stagnant market, delivering low margins while still requiring ongoing investment to meet changing regulations; its main attraction for IOCs is its countercyclical nature. Companies have, therefore, operated refineries on a "care-and-maintenance" basis, with investment kept low.

A new era

Fortunately, the future looks bright. The refining industry is entering a new "benign era," characterized by improved margins and a basis for steady, pragmatic investments.

The impetus will be broad-based demand growth, driven by economic growth in all regions and industries. The major share will come from non-OECD countries, especially China and India, with demand rising to more than 50% of total global demand, driven by rising industrial production and higher living standards.

In the OECD, demand for refined products will also grow, but more slowly. Demand will occur due to GDP and transportation sector growth, with further efficiency improvements that are more than offset by greater product demand and increased purchases of sport utility vehicles.

During the last several years, two changes have combined to produce significant local supply-demand imbalances in refined-product demand:

- A steady shift towards the top of the barrel because demand for such heavier products as fuel oil has decreased.

- Demand switching in key regions between refined products. For example, rising US demand for low-sulfur gasoline and European demand switching from gasoline to diesel.

Refiners have sought to address these imbalances without major investments in new refining capacity, which has resulted in a substantial international products-trading market. Rising volumes and demand levels have changed these international trades from isolated, one-on-one deals to standard trades within a global market.

Information flows, logistics and transportation, contracts and settlement mechanisms now make this market self-sustaining. Local demand imbalances are rapidly identified and matched with supplies from other regions.

The international refined-products market is no longer a series of separate regional markets, which previously allowed supply bottlenecks to support high margins in specific local markets; future demand will naturally flow to where margins are out of line. Refining is, and will increasingly become, a single global market in which regional margins move in sync.

Globalization of the refined-products market will also create another criterion for refiners to satisfy when installing new capacity. Instead of a refiner justifying capacity to meet rising demand in a regional market, it will have to justify capacity based on incremental savings from meeting that demand locally vs. importing the product from other regions. This is a more-stringent global justification based on an international production-supply-demand balance.

Utilization rates will also improve in the next few years. Net demand increases of 0.5-1.0 million b/d/year during the next 3 years are likely.

No significant new capacity is to come online in this period.

In reality, impending new regulations are likely to close some marginal refineries, reducing available supply.

Existing capacity must meet this additional demand, which will increase utilization rates, now finally at attractive levels for refiners—more than 90% for many US refiners.

There is a fundamental difference between this "benign era" and previous upturns.

Light crudes will continue to command a price premium and tend to displace heavy crudes in production, with light-crude production increasing to meet rising demand. As demand continues to rise, however, incremental supplies will increasingly come from heavy sour crudes, allowing complex upgrading refineries an advantage.

Hydroskimming refineries must run light, sweet crudes to make acceptable margins, given the lack of demand for the bottom of the barrel. With healthy margins, they will increase utilization rates, bid up sweet light crudes, and widen the differential to heavy crudes. The best complex refiners will run these heavier crudes and generate higher margins, which will widen the margin gap between them and hydroskimmers; this scenario is much more significant than in the past.

In addition, the market is moving to more-stringent product specifications, which will require more product cleanup (lower sulfur, benzene, etc.). The greater differential in demand, and therefore price, between the light and heavy ends of the barrel will reward advanced complex-refinery capability.

The result will be a wider gap between hydroskimming and more-complex refineries. The complex refiners will essentially control hydroskimming profitability. And the hydroskimmers will try to postpone the inevitable invest-divest-close decision.

Refiners must be able to convert a barrel of oil into a product mix that matches demand to survive in the long term. This requires upgrading capabilities.

Leaders in the new era

Whereas the benign era will deliver strong margins for all refineries, it is ultimately an opportunity for leading refiners to fund further improvements and outperform other refiners.

The best refiners will be those that can deliver in five areas:

- Customer-led supply chain optimization.

- Aggressive portfolio management.

- Nimble, market-based manufacturing strategy.

- Operational excellence.

- Workforce motivation and management.

Supply-chain optimization

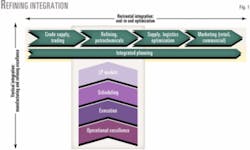

For the first time, advances in information technology (IT) allow companies to manage and optimize the entire hydrocarbon supply chain horizontally as well as vertically (Fig. 1).

Integrated IT systems, streamlined business processes, and consistent data allow optimization from crude acquisition to product delivery to consumers. IT, however, just enables delivery; success is 10% due to IT and 90% due to business practices.

Substantial organizational change is needed for this new way of working. Separate departments that commonly optimize their own operations must learn to work together to deliver the best solution for the organization as a whole, even when it is less than optimal for their own operations.

Software suppliers work with industry forums and Accenture to develop standard products for the oil industry. In addition to product development, these forums also help develop performance measures, new business processes, data definitions and industry standards to support IT solutions, and the organization and performance structures to motivate personnel to work differently.

The result will be companies that:

Are more agile and able to replan on short notice to capitalize on market opportunities.

Refiners will be able to decide which market opportunities deliver maximum additional value to the company, giving them a clear advantage over their competitors.

Currently, no company has fully implemented this complete solution. Most are working on it and all have implemented parts of the total solution. In the future, refineries that operate as an effective part of an optimized, integrated, end-to-end supply chain will have a critical competitive advantage.

Aggressive portfolio management

High-performing refiners constantly evaluate their portfolios of refining assets against their business strategy and competitors' facilities. They ensure that all their assets deliver more value to them than to a competitor, have a market advantage, and achieve attractive margins and ROACE.

The key attribute is a market advantage (process flexibility, geographic location, optimized crude supply, refinery configuration, etc.) that leads to attractive margins.

Leaders will invest to strengthen this advantage and the returns from these assets. They will also make the difficult decisions to sell or shut down those assets that do not enjoy a market advantage, whether profitable or not.

Being the best asset in a given portfolio is not good enough. High-performing refineries will be those that evaluate themselves against all other comparable assets and invest to establish an advantage in their chosen markets.

Manufacturing strategy

Refiners will increasingly follow a market-based manufacturing strategy. The refiner's key to success is having a clear knowledge of its role in supplying a market and focusing all the operations on that role.

Knowing the market better than the competition will distinguish the high-performing refiners. This market-based strategy will lead to five distinct types of refineries:

- Scale—high-demand growth. High-performing refineries that focus on high-demand growth markets will be supersites (>12 million tonnes/year [tpy]) such as Reliance Industries Ltd. in India. These relatively new refineries will be designed, built, and expanded to meet future demand growth. They will meet demand either through increased utilization or cost-effective expansions already designed into the plant.

Total AS' Mitteldeutsch refinery, for example, with an initial capacity of 7.5 million tpy 6 years ago, is now processing 10.7 million tpy. Economies of scale establish cost leadership in chosen markets, which delivers attractive margins.

- Sharing—saturated markets. High-performing refineries in saturated markets (little or no demand growth and sufficient or excess supply) will be those that achieve supersite economies of scale by collaborating with competitors.

The absence of growth prevents them from expanding to supersite capacities. Instead, their route to scale economies will be accomplished via single-site or multiple-site joint ventures.

This will reduce capital expenditures (shared investments) and operating expenditures (scale efficiencies, shared services) vs. "standalone" competing refineries. This will help refiners establish a competitive advantage in these static, mature markets.

- Niche—specialist producer. A few refineries will maintain a competitive advantage by focusing on highly specific, specialized markets. These are, by definition, comparatively small markets that do not justify new refinery investments due to their size.

BP PLC's ERE Lingen refinery is a relatively small inland plant without the benefit of scale economies and incurring high transportation costs due to its inland location. Because the plant is designed for sour feedstocks and has one of the highest conversion rates, however, it services its regional market cost-effectively.

Another example is Nynas Petroleum NV in Sweden, which has an advantage as a specialist producer of different bitumens for road use.

- Price—large dependence on third-party outlets. In some Western markets, oil companies do not own much of the downstream retail market. In France, for example, hypermarkets own more than 50% of the retail fuels market.

Leaders in these markets will be refineries that understand the market, their customers' positions, and their competitors' positions better than they do. They will continually optimize the refinery gate price on a deal-by-deal and customer-by-customer basis, knowing the margin they will make on every deal and being ready to turn demand away when it is not profitable.

Survival in these markets will require that a refiner have higher margins than its competitors. Local customer demand will guide these high-performing refineries in these markets. The refinery will base all decisions—such as crude acquisition, refinery configuration, throughput, and stock levels—on that demand they can service more profitably than their competitors.

- End-to-end—oversupply. In markets with significant excess supply, refiners will focus on optimizing the end-to-end supply chain. Leaders will be those companies that continually reoptimize the whole supply chain to service the markets most cost-effectively and focus on demand that generates acceptable overall margins.

The refinery may make a low margin, but if the overall end-to-end margin is acceptable, then the refinery has a secure position as part of this overall optimized supply chain, provided its cost base is in-line with competitors.

The high-performing refiners in these markets will be lean, low-cost producers that can rapidly replan and reoptimize, are effective at working with the other parts of the supply chain to reoptimize, and can always deliver their commitments.

Operational excellence

High-performing refineries recognize that however cost-effective and efficient their operations appear, there is always room for further improvement.

Refiners have historically used periodic benchmarking (Fig. 2) to assess themselves vs. their peers. Based on these results, refiners develop and implement action plans to address problem areas identified in the benchmarks. In the future—typically 2 years later—the benchmarking exercise is repeated and the impact of the actions becomes clear.

High-performing refineries are now starting to use profitability assessments to help them improve operations. This approach integrates benchmarking, action plans, and business performance measurements into an ongoing cycle.

Benchmarking is based on an underlying model of refinery operations that directly links performance measures to causes. Desired performance changes generate action plans and expected revised benchmarks, which show the impact of proposed changes and the actions required to deliver them.

As actions are completed, the benchmarks can be recalculated, allowing a refiner to continuously assess business performance. This allows refinery managers to continuously monitor performance changes and adjust action plans to maximize improvements in refinery operations.

Workforce motivation and management

High-performing refineries will outperform other refineries by using investments in facilities and people to improve substantially their operations and competitive position.

This will involve unprecedented changes for personnel, who will have to implement investment projects, steer improvement plans, learn new ways of working and teaming with other functions in oil companies—all while continuing to operate the business cost-effectively and efficiently.

Investment in refinery employees is crucial to these improvements. This will require:

- Honest, open, and visible leadership that sets a clear direction and actively supports the necessary changes.

- Investment in training and change management to help people to understand and support the proposed changes.

Many refinery employees are highly skilled with many years of industry experience. Substantial changes will generate uncertainty and concerns, which, if not addressed, will slow and even derail improvement programs. Leading managers understand this and will invest the time and effort to gain the support of their staff.

The author

David Mowat ([email protected]) is the global managing partner of Accenture's energy practice. He has 26 years' experience in the upstream and downstream oil and gas business. Mowat joined Accenture in 1978, was made partner in 1989, and led the UK energy practice in 1992-99. He holds a BS in civil engineering from Imperial College, London.