Study details errors contributing to high-pressure pipeline infringement

A new case study written by Julian Williamson and Christine Daniels and published by the UK’s Health and Safety Executive details issues contributing to a third-party pipeline infringement in February 2007. In its findings, the report emphasizes that even ostensibly informed individuals will both make errors and commit violations and that effective safety policy must account for this.

Based on interviews conducted in August-September 2007 with those involved in the incident, the report breaks identified risk factors into six main categories:

- Systemic risk factors.

- Organizational change.

- Communication.

- Planning.

- Risk awareness, perception.

- Provision of risk information.

It then makes recommendations for managing risk of third-party damage in each category.

Infringement

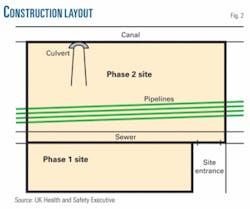

The project in which infringement on the pipelines occurred involved two phases. Phase 1 consisted of construction of a commercial building and Phase 2 construction of an accompanying car park. The work site is adjacent a canal and opposite an oil refinery and tank farm (Fig. 1). A concrete sewer pipe and four pipelines run across the site parallel to the canal.

The UK’s National Grid Gas defines a major accident hazard pipeline (MAHP) as operating at greater than 7 barg and requires cathodic protection on such lines. Two of the four pipelines crossing the site met this criterion. Fig. 2 shows the site, with the pipelines as follows (starting closest to the building and moving toward the canal):

- 32 bar (high pressure, MAHP) 16-in. steel.

- 32 bar (high pressure, MAHP) 24-in. steel.

- 7 bar (intermediate pressure) 14-in. steel.

- 7 bar (intermediate pressure) 10-in. steel.

In August 2006 the client’s chairman met with the principal contractor and NGG to determine what would be required to turn the unused portion of the lot into a car park over the pipelines. The client agreed to perform NGG-supervised trial-hole digging to find the exact position and depth of the pipelines. This marked the principal contractor’s last involvement in Phase 2 of the project.

The client directly contracted the subcontractor for Phase 2 in December 2006. The projected duration of the project (30 days) required that it be registered with HSE, but this was not done. The subcontractor began ground clearance in January 2007, without any notice being given to NGG.

An NGG inspector making a routine visit to a neighboring site noticed the work on Feb. 14, 2007, and stopped it immediately. The inspector found that the pipes themselves had not yet been damaged, but their CP cables had been uprooted during excavation and any pipeline markers had been moved to the site perimeter (Figs. 3-4). Ground preparation for Phase 2 also destabilized the shoring along the canal.

The client incurred the costs of repairing the canal, replacing the local CP apparatus, and associated delays in completing the site and securing tenants.

Risk factors

The HSE report listed a number of risk factors associated with this project in each of its six categories.

- Systemic risk factors. The system in place depended on the knowledge and competency of key individuals, relying on them to comply with defenses and procedural barriers. The system also used an overly complex series of arrangements between contractors and subcontractors, working against communication at the site level, while the lack of an effective risk-management system led to on site confusion regarding individual risk-management responsibilities.

- Organizational change. Rapid organizational change furthered this confusion in roles and responsibilities. Staff allocation did not necessarily follow an assessment of a given individual’s experience and competencies, a situation only worsened by a dominant client chairman with relatively little experience of his own in managing construction projects near MAHPs.

- Communication. A lack of formal coordination between the project designer and the client regarding communication with the NGG and acquiring proper authorizations contributed to assumptions by the client that formal approvals had been given when this was not the case. Similarly, NGG approval hinges on the knowledge of the individual making the request, without any systemic connection to any previous requests that might have been made regarding a specific site.

A lack of formal procedures for passing risk information from client to contractor to subcontractor became even more hazardous when a breakdown in the relationship between the client and the principal contractor occurred right before the project was handed to a subcontractor for the second phase of construction. - Planning. Commercial pressures for project completion led to an ad hoc approach to planning that gave productivity precedence over risk management. Other commercial pressures led the subcontractor to be on site only intermittently, weakening verification of safety procedures.

- Risk awareness, perception. Generally low awareness existed regarding both the consequences of damaging MAHPs and the role of the NGG in addressing these risks. Ongoing construction and existing car parks in the immediate vicinity of the work site further deadened any potential risk awareness.

- Provision of risk information. The subcontractor did not verify the accuracy of topographical information. Communication of risk information between the principal contractor, designer, client’s lawyer, and client chairman was abridged. The subcontractor contacted NGG (via telephone using the number found on a pipeline marker) but might not have been categorically instructed to stop construction at that time.

Recommendations

The HSE study makes several recommendations addressing the problems discovered. In addition to accounting for the fact that individuals will make errors and commit violations, a system for communicating risk information should be simple enough that the proper information reaches the site level.

Organizational change should occur in a manner preserving the clarity of individual roles and responsibilities and allowing challenges or questions, particularly regarding risk management, to move up from the construction-site level. Individuals should also be aware of their own professional responsibilities when taking on new tasks.

The person communicating regarding hazards with the pipeline operator on behalf of the project should be qualified to do so and documented procedures should exist for passing on his or her knowledge to any successors.

Communication of risks should take place at every stage from design through completion of construction.

Project timescales should not contribute to productivity taking precedence over risk management. Experience and competency should guide contracting and staffing decisions.

Company-wide awareness of MAHP hazards and the pipeline operator’s role in managing these should be established. Such awareness will help foster an environment in which the accuracy of risk information is confirmed, communication with the operator happens at the planning stage, and any required authorizations are transmitted clearly to appropriate parties.