Shale gas development altering LPG demand, trade

Fernando Leija

Ronald L. Gist

IHS Energy Insight

Houston

The LPG market in the US is experiencing a remarkable transformation due to the rapid increase in supplies being produced from both tight oil and shale gas formations. This production has resulted in shifting global LPG trade patterns as the US continues to move from a net importer of LPG to a net exporter.

The successes in the US have encouraged several countries to develop their potential shale gas reserves, which would likely result in rising LPG supplies, depending on the quality of the shale reserves and the ability of these countries to develop them. Countries with shale reserves are on different development timelines, determined by such factors as infrastructure, political climate, availability of investment capital, mineral rights ownership, and market supply-demand balance.

Although international base demand for LPG will continue to grow, rising LPG supplies from shale gas may create opportunities beyond traditional markets, such as on-purpose propylene production.

LPG production

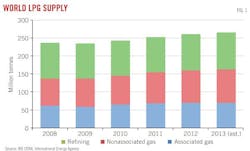

Data compiled by IHS Energy Insight shows world LPG production in 2012 rose to about 260 million tonnes, an increase from 2011 of around 8 million tonnes. The largest producers of LPG include the US and Canada, the Middle East, and Asia.

Regionally, the US and Canada have the highest LPG production at about 24% of the world total, with the Middle East only slightly less.

Worldwide, natural gas processing contributes about 60% of total LPG supply, with refining providing the remaining 40%. The range varies widely from region to region, depending on the resource base relative to the size and complexity of the refining system. For example, in the Middle East, about 92% of regional LPG supplies derive from natural gas processing and only 8% from refineries. Conversely, in Far East Asia, IHS estimates natural gas processing supplies less than 1% of LPG supply and refineries contribute about 99%.

The contribution to LPG production of tight oil and shale gas is evident in global supplies. Nonassociated gas production is the fastest growing source of global LPG supply. LPG extracted from associated gas should also rise as crude oil production rates rise. Refinery expansions are also contributing to higher LPG production, but at a slower rate (Fig. 1). Global LPG supplies will grow quickly, particularly in the Middle East, Asia, and the US.

Shale gas resources

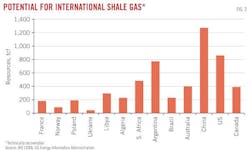

Except in the US and Canada, shale gas resources have yet to be significantly developed, but major shale gas basins have been identified in many regions (Fig. 2).

Although several countries have large shale gas reserves, many obstacles stand in the way of monetizing potential LPG supply. Geologically, the shale must be deep enough to develop reservoir pressure, but not so deep as to make drilling costs excessive.

The shale seam must be thick, contain large amounts of organic material, have low thermal maturity, be relatively uniform over a large area, and be brittle enough to make fracturing effective. Assuming the proper geological conditions, additional external constraints may impede resource development.

As a model, the US has been successful in developing NGL shale resources for several reasons, including:

• Strong demand for each NGL product.

• Advanced technology and expertise.

• Private ownership of mineral rights.

• Extensive infrastructure (processing, transportation, and storage).

• Competition among companies, which spurs innovation.

• Governmental regulatory support.

Outside the US are several impediments to the development of LPG from shales.

Primarily, in order for the shale resources to be developed, a country's domestic markets must require additional supplies of natural gas. That country must acquire the technology and have the skilled labor to develop the assets.

If unable to develop shale resources through national energy companies, the country must also be able to attract investor capital. The country should not restrict access to the natural resources or assess taxes that make investing difficult.

And, there must be adequate transportation and processing infrastructure and access to water for use in fracturing wells.

Possible development

The following discusses countries with the largest recoverable shale gas resources:

• China will likely remain a net LPG importer as its economy continues to grow and the country increases its use of LPG for a wide variety of end uses. China holds the largest amount of technically recoverable shale gas in the world at 1,275 tcf.1 China, however, must overcome complex geographical conditions and limited access to water.

Another major factor that could impede development of shale gas is the existence of relatively cheap coalbed methane that might be preferentially developed.

• Argentina is one of the major exporters of LPG in Latin America, along with Trinidad and Peru. The country has exported the most LPG in Latin America since 2005.2

According to the US Energy Information Administration, Argentina has the third largest shale gas reserves in the world, measured at 774 tcf. YPF, Argentina's recently nationalized oil company, has drilled in the Bajo del Toro block of Neuquen's Vaca Muerta—a shale formation estimated to contain more than 21 billion boe (OGJ Online, July 11, 2012; Apr. 8, 2013).3

The primary obstacles to developing LPG in Argentina are the lack of investment capital available due to the political climate, import restrictions on equipment, and water availability. Investors hesitate to invest capital in a country that in 2012 nationalized YPF from Spain's Repsol (OGJ Online, Apr. 23, 2012).

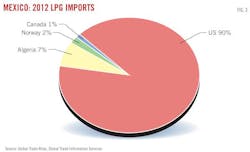

• Mexico is among the highest per-capita residential-commercial consumers of LPG in the world with about 8 out of 10 homes using LPG. Although LPG demand has decreased somewhat since 2000, IHS forecasts demand to remain flat through 2015.

Mexico currently imports nearly 30% of its total LPG demand and accounts for roughly 40% of total LPG imports into Latin America, according to the Global Trade Atlas published by the Global Trade Information Service. The country imports large quantities of LPG from the US, as well as from several other exporting countries (Fig. 3). Consequently, Mexico has an incentive to produce as much LPG domestically as possible.

Mexico holds the fourth largest shale gas reserves in the world, about 681 tcf.1 Most of Mexico's known wet shale gas assets are an extension of the Eagle Ford shale gas play in southern Texas.

Pemex, the country's national oil company, expects to be able to monetize its shale gas resources at a natural gas price of $3-$4/MMbtu. Pemex plans to drill several shale gas wells in 2013 (OGJ Online, Mar. 11, 2011).4 A major obstacle is the controlled budget of a state-owned company that may retard development in favor of existing conventional crude oil reserves. Additional concerns are security of equipment and employees.

• Australia will continue to be a major exporter of LPG to Northeast Asia (Japan, South Korea, China, and Taiwan) and Southeast Asia.

LPG consumption in Australia is roughly 1.8 million tonnes/year (tpy).2 IHS data show about 55% of LPG demand in Australia is for direct automotive use (autogas), but autogas consumption is likely to decrease due to reduced government support.

LPG production is currently stable but is likely to increase substantially beginning in 2017 in the western part of the country. New developments there by 2020 could represent more than 40% of total LPG production in Australia.5

Australia has the fifth largest shale gas reserves in the world, measured at 396 tcf by EIA. In order to develop its shale gas, Australia must overcome the high costs of building needed infrastructure, the high costs of labor, and an oversupplied domestic natural gas market.

• In Canada, declining gas production has pushed NGL production lower. Canadian gas exports are continuing to decline, as its only customer—the US—has been able to develop its own gas supplies through shale plays.

Canada exports both propane and butane to the US. Field butane is mostly blended into gasoline and used as a crude oil diluent. Natural gasoline is also marketed as a diluent.

If planned LNG export projects come to fruition in Canada, natural gas production would increase. This increased production might generate additional LPG, depending upon which plays are exploited. Since Canada already as a surplus of LPG, incremental supplies would likely need to be exported into international markets.

Canada holds the world's sixth largest technically recoverable shale gas reserves at 388 tcf,1 with a great opportunity to access wet shale gas. We believe that, as new plays become developed, LPG production will eventually stop its decline and begin to increase again.

Global demand

Rising global LPG supplies during 2012 pushed up world LPG demand by about 8 million tonnes to nearly 260 million tonnes. Asia represented the largest share of demand at nearly 35%.2

Asia and the Middle East continue to be strong growth markets for LPG. During 2002-12, Southeast Asia experienced the highest compound demand growth of more than 15%/year. Other high LPG demand regions include North America, Europe, and Latin America.

Global demand for LPG in the residential-commercial sector continues to increase, but high prices and the weak global economy have slowed growth in some countries. This large end-use sector will continue to be important to the future of the LPG market.

Increased LPG supply will likely depress LPG prices compared with crude oil, so that LPG may become more attractive to global residential-commercial LPG markets.

We also expect large amounts of LPG to be substituted for naphtha feedstocks in ethylene crackers in olefins plants with the flexibility to switch fuels.

Rising supplies of LPG, however, are also leading to increased interest in the use of dehydrogenation technology to produce propylene directly from propane and to produce butadiene from butane.

Dehydrogenation demand

As a result of the development of US shale gas plays, ethane prices have been low relative to other ethylene plant feedstocks. Thus, petrochemical companies have been taking the opportunity to utilize this cheap ethane feedstock through steam cracker conversions, additions, and planned new builds.

Ethane, however, produces relatively less propylene, butadiene, and heavier co-products than other feedstocks. For perspective, cracking ethane yields 20-30 lb of propylene for each 1,000 lb of ethylene. Propane cracking, however, yields more than 300 lb of propylene/1,000 lb of ethylene.

With the increased development of NGL-rich fields, propane supplies have outpaced base demand in the North America, creating an opportunity to use propane as a feedstock for propylene production. The primary source of additional propylene will be from propane dehydrogenation (PDH).

Six PDH units are to be built in North America by 2018 with demand totaling about 150,000–180,000 b/d of propane. Increased use of propane by PDH units would not only help soak up the growing propane surplus, but also alleviate some of the domestic propylene shortfall.

Enterprise Products, Dow Chemical, Formosa Plastics, Williams, and others have announced PDH projects in North America (OGJ Online, Jan. 8, 2013; Jan. 31, 2013).

In China, PDH projects could total almost 4 million tpy of propylene production capacity, if all of the announced units are built. Although we see that scenario as unlikely, we do expect PDH to be a major consumer of propane, which will likely result in increased propane imports. With limited refinery propane supply, China is interested in developing PDH projects based on LPG imports.

A similar product shortage is occurring with butadiene as US olefins crackers favor light feeds. US demand growth will continue to be covered by imports of butadiene or crude C4s. Another supply source, however, could be on-purpose production from butane dehydrogenation (BDH) plants. Up to three BDH plants could be started up shortly after 2020 with an expected total consumption rate of nearly 40,000 b/d of normal butane.

Ethane waterborne exports

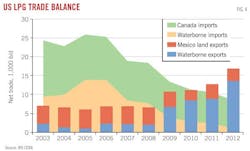

Not only has development of LPG supplies from shale gas facilitated more use by the domestic petrochemical industry in the US, it has also resulted in an increase in LPG exports. In 2011, the US became a net exporter of LPG (Fig. 4). Initially most of these exports from the US were to Latin America. As the surplus expands, however, exports will likely be increasingly destined for both Asia and Europe.

In addition to traditional LPG trade, as shale plays have been developed in the US, ethane production has outpaced domestic demand. Ethane will likely remain oversupplied until additional ethylene capacity comes online in the US. In Europe and Asia, steam crackers are generally configured primarily to use naphtha and typically have no access to cheap local ethane supplies. Because US ethane has become cheap relative to LPG and naphtha as a steam cracker feed, interest in exporting ethane to Europe has developed.

Ethane is typically transported in pipelines. Waterborne delivery of ethane poses unique difficulties. A major one is construction of fit-for-purpose refrigerated ships and handling equipment at both export and import terminals. Another is the retrofitting of petrochemical crackers to use ethane where naphtha may be the typical feed.

Ineos took a major step in waterborne shipping of ethane when it announced in late January 2013 that it had entered into a 15-year agreement with Evergas to build new refrigerated ships that will transport ethane from the Marcus Hook refinery complex near Philadelphia to Rafnes, Norway, by first-half 2015. The ethane will be supplied to Marcus Hook by Sunoco's Mariner East pipeline project (OGJ Online, Oct. 8, 2012).

Ineos has also agreed to a long-term deal with Range Resources to provide the ethane beginning 2015.

US export infrastructure

The US has moved from being a net importer of LPG to becoming a net LPG exporter. It will likely become one of the world's LPG largest exporters, behind only the Middle East. Butane has been exported from the US West Coast to Asia for many years, but LPG exports from the East Coast were uncommon for about a decade before 2012.

(EDITOR'S NOTE: For a more detailed account of the development of US LPG export capability, see the box p. xx in the accompanying article.)

Structural waterborne LPG exports to Latin American ports have been common for many years, but large-scale exports of propane from the US Gulf Coast to Latin America and Europe are relatively new. By yearend 2012, the US waterborne exports totaled roughly 5 million bbl/month of LPG. Propane represents roughly 90% of the total and butane about 10%. About 90% of LPG exports were from the US Gulf Coast.

To capitalize on these LPG export opportunities, however, new infrastructure had to be developed in the form of waterborne terminals, storage, and pipeline projects. Several LPG marine terminal projects from the US have been announced by midstream companies to be in service by 2015.

The first expansion of an existing export terminal was completed by Enterprise in March 2013 (OGJ Online, Mar. 7, 2013). An expansion at the existing Targa export terminal is to be operating by fourth-quarter 2014. These two expansions should roughly double the combined capacities of the terminals to about 10 million bbl/month. Other companies reported to be considering new export terminals include Sunoco Logistics, Lone Star NGL, Vitol, Occidental, and Intercontinental (OGJ, May 7, 2012, p. 104).

A key question for the future of the NGL industry is whether the North American success story can be replicated in differing geologic, political, and business climates. An affirmative answer to this question would profoundly affect global NGL markets, altering trade patterns, pricing mechanisms, and consumption of LPG in traditional residential-commercial sector and non-traditional uses.

References

1. "World Shale Gas Resources: An Initial Assessment of 14 Regions Outside the United States," US Energy Information Administration, Apr. 5, 2011.

2. World LPG Market Outlook, IHS Energy Insight, 2012.

3. Bajak, Aleszu, "American companies cautiously optimistic about Argentina's shale reserves," LatinAmericaScience.org, June 6, 2012.

4. "Mexico's Pemex sees profits from shale gas on rising prices," Reuters, Oct. 1, 2012.

5. "Major LPG Market Developments Australasia," Elgas, Anthony Gilbert, 2012.

The authors

Fernando Leija ([email protected]) is a director at IHS Energy Insight in the Houston office. Before joining the company this year, he worked at ConocoPhillips and a midstream consulting firm. He holds a BS in economics from the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, and is a chartered financial analyst. Leija is also a member of the Houston chapters of GPA and the US Association for Energy Economics.

Ronald L. Gist ([email protected]) is a director in the Houston office of IHS. He began his career with EI DuPont de Nemours & Co. in 1971 after receiving both BS and MS degrees in chemical engineering from Colorado School of Mines. Gist has chaired GPA's market information committee and served as 2009-10 chair of the Houston chapter of GPA.