Leading indicators measure maintenance effectiveness more accurately

The current plant environment requires measurements that can predict, not just measure, the outcomes from maintenance activities. One strategy is to examine a set of leading indicators to judge how well the investments are going to pay backin advance of the results, which is a lagging indicator.

Maintenance personnel need to measure interim indicators that affect the final outcomes for the month. Measuring maintenance is like investing in the stock market; investments should be geared to high value returns that are provable.

If the leading indicators are "bearish," there is time to take corrective actions. If the leading indicators are "bullish," the maintenance efforts (investments) are going to produce the required return.

Managing the up and down trends of leading indicators is essential to successful management of maintenance investments.

One must measure the leading and lagging indicators, however, within some context or overall process. This article describes such a process called the Managing System.

This system integrates the plant's overall strategy with a series of cascaded goals and objectives that are linked down through the organization.

It then establishes the measurements of these goals at each level, and the key process indicators needed to ensure that the processes remain healthy.

These measures are a set of leading and lagging indicators.

The key is in using the system, which is the primary method to review performance against the plan. To make this work, the plant owner should use the system at all levels of the organization, conduct reviews on a scheduled frequency, publish measurement results, and hold people accountable for results.

Reviewing the leading indicators weekly gives one the ability and time to correct deviations before the lagging indicators are reviewed at the end of the month.

Some plants have a semblance of this system in place, but it is often disjointed and based on lagging indicators that do not tie the strategic direction to tactics used at the floor level.

In most cases, the plant uses wrong measurements that do not relate to the desired behaviors; it does not provide a vehicle for change, therefore.

While it is important to measure, it is imperative to measure the right things. Maintenance measurements are a part of a global set of indicators that gauge a facility's viability.

It is important to ensure that one measures the right sets of information.

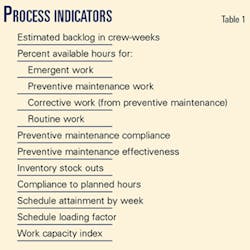

Table 1 shows leading or "process" indicators.

This article mainly covers these process indicators. Outcome indicators are important, but most of them are well known and require just a brief discussion.

Estimated backlog in crew-weeks

Backlog is defined as the total amount of work that has been identified but not yet completed, including work in progress, but excludes preventive maintenance (PM) inspections.

It requires that all work requests receive a rough estimate from the planner before going into the backlog.

It is calculated by dividing the estimated work in the crew's area by the available crew hours in a week.

The same indicator applies to total work in the department and total in the crew.

The backlog indicator should be managed to 5-7 crew-weeks. It balances the amount of work received vs. executed, and justifies the need for contractors as supplementary help if the backlog gets out of control.

The reason for the 5-7 week level is to allow a buffer time for planning and logistics to prepare and gather the resources required to perform the work. The organization should use a forward scheduling model.

This measure can also show the backlog by type of work; an increasing trend in work resulting from inspections would show that a PM program is more effective or that equipment is quickly deteriorating.

Percent of preventive, predictive work

PM is the base workload for the organization because it is a known quantity and can be planned well in advance. This base load should be smoothed through the year so that the fluctuation of manpower requirements does not vary significantly.

A plant should spend 30-35% of available hours on this type of work because it is the basis for getting control of the equipment. Better PM means less emergent work.

Most plants conduct too much PM. Most plants incorrectly use original PM routines that were established when the equipment was installed.

PM routines are seldom rationalized or justified based on equipment failure history.

The maintenance program should assure that the mix of PM and predictive maintenance is correct, which requires less manpower, and that the program is based on a rational approach.

Percent of routine work performed

This is basically all of the other work that entails an expense. The target is about 10% of all work.

Type of work

Multiple indicators show the "big picture" of what is happening in a plant.

Analyzing the percent of available hours by type of work shows the macro view; it shows whether the maintenance department is in control of the facility. These variables should be charted weekly.

In most cases there is only one indicator of PM performance in a facility—PM compliance to schedule.

But this tells only a small part of the story and is too easy to manage in the field.

Often a worker will fill out a form to show the routine as complete and to get credit.

There are generally no qualitative measures associated with PM; without this type of measure, one cannot know if the investment in PM is justified.

PM compliance

This is the measure of whether the program is followed according to schedule. If the requirements are rationalized and smoothed out, it is easier to manage this process, and the measurement should be more stable. Mature and proactive organizations settle for no less than 100% compliance because this is the key to getting control of equipment in the plant.

PM effectiveness

This indicator measures the amount of work generated from PM, measured as defects found/PM performed. It determines whether the frequency of a routine is correct or needs to be revised.

If few or no defects are found, the PM is either not doing its job or the frequency of inspection should be lengthened. This aspect is usually missing in PM programs and is key in gaining a balanced view of the health of the process.

Inventory stock outs

Spare parts supply can have a major influence on how well the maintenance department can perform its work. How well the supply chain is working can determine maintenance overall effectiveness.

The major leading indicator for inventory is stock outs, which measures the number of items issued vs. the number of items requested. This should be measured weekly, as with all other leading indicators, and should be a consistent 97%.

These numbers, however, are based on a maintenance operation that uses advanced weekly schedules and does not schedule work unless the parts are on hand. Too often the spares warehouse is blamed for ineffective, reactive requests for parts. These requests do not give them adequate time for the supply chain process to work.

Work management process performance

Work management is the most important process in maintenance and contains all the parts of the work-order system. Knowing how well this process is operating is crucial to a plant's success.

The root question is: Who is the customer of work management?

In essence the maintenance crews are the customers, and their productivity directly reflects how well the process is performing.

Most crews perform poorly due to barriers that prevent them from working.

These barriers include: looking for parts or waiting for instructions; a lockout; waiting for an operator to shut down the equipment; or waiting for a crane to lift a component that no one scheduled, etc.

Schedule compliance

A plant with forward scheduling will have the current week's schedule prepared a week in advance. One can then measure how many jobs were completed according to schedule. This includes all PM work because, by definition, this is work planned in advance and scheduled accordingly.

This indicator should be 90%, which takes into account some level of emergent work, which is specified at 10% or less. This is also measured on a weekly basis according to crew and department total.

Attaining these figures takes cooperation from the production department. This is the first measure of work-management effectiveness.

Schedule loading factor

This measures the percent of available man-hours that are scheduled every week.

High schedule compliance with few people scheduled makes little sense. Much debate has centered on what this number should be—either 100% or 90% loading factor.

A 90% load assumes that the plant has about 10% emergent work on a continuing basis.

More stable operations where emergent work is low uses 100%, but about 5% of the man-hours are scheduled for low-priority tasks.

When the schedule is broken, these people are sent to perform the emergent work. Schedule loading is the second factor in the work management measurement.

Wrench time

This is a measure of the percent of a workday a craftsman spends performing actual work. In reality, it is a lagging indicator, but it is part of the overall measure of work management effectiveness.

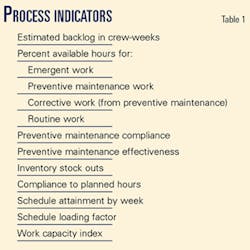

The world-class number for this indicator is about 65%, but most clients that we initially assess are measured at 28-35% (Fig. 1). Workers face many barriers that keep them from being effective; typically, there are wait, travel, and materials delays, which are all controllable in a proper work management process.

Wrench time should be measured quarterly with a study using multiple assessors that spend several days with a each craftsman and measure the time spent in each category (Fig. 1). Studies should also occur for non-PM work.

Gauging work management process

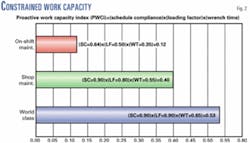

One method to measure overall effectiveness of the work management process is the proactive work capacity index (PWCi). Schedule compliance, schedule load, and wrench time are the information needed to gauge this process.

The indicator is calculated as:

PWCi = (schedule compliance) x (schedule load) x (wrench time)

Using the best-of-class numbers for the individual components, the PWCi is:

PWCi (world class) = (0.90) x (0.90) x (0.65) = 0.53

Fig. 2 shows this graphically. In the graph, the first bar was for a client we assessed, the second bar is a projection following a 1-year intervention, and the third bar is for a world-class organization.

This index should be calculated weekly and trended over time. It is the best overall measure of the effectiveness of the entire work management process because it measures the key factors that may need improvement: scheduling at a maximum number, complying with that schedule, and the productivity of workers that are executing the individual jobs on the schedule.

There are other indicators that can be used, but they measure other subsystems. It is permissible for a plant to measure more than these indicators; however, too many measurements dilute the effect of the important numbers.

Lagging indicators

Lagging or outcome indicators are generally those that are reported to management and form the basis of the overall view of the maintenance operation. These are used to gauge how well the maintenance department is performing.

Few plant managers or vice-presidents of operations care what the proactive work capacity index was last week, nor will they fully understand its impact. That is maintenance's job and measurement set.

The outcome indicators are important because they do tell the final story of an organization's effectiveness.

Cost/unit produced, maintenance cost as a percent of replacement value, equipment uptime, and inventory turns all indicate performance.

They are the higher-level indicators of long-term success when maintenance is viewed as a business.

The maintenance manager must remember to:

- Emphasize the need to manage maintenance incrementally.

- Watch those things that constitute the end result that is used to judge maintenance effectiveness.

- View all of the indicators, both leading and lagging, as a whole picture. Never rely on one or two to predict success.

- Keep a manageable set of indicators, and follow the principles of the managing system to promote change.

- Manage to trends rather than single point numbers.

- Never react to instantaneous information—look for trends.

- Share the results with everyone, good or bad—maintenance relies on others to perform, so tell them how they are doing.

Based on a presentation to the National Petrochemical & Refiners Association 2004 Annual Meeting, Mar. 21-23, 2004, San Antonio.

The author

Ralph D. Hedding is vice-president of international operations for Strategic Asset Management Inc., Unionville, Conn. He has 34 years' experience in asset management and reliability. Prior to SAMI, he was director of consulting services for CMMS system software provider Marcam Corp., Burlington, Ont., then vice-president of management consulting firm Resource Dynamics Inc., San Francisco. Hedding also managed the maintenance, engineering, and operations for Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp. and American Brass Co. and was an operations manager at Logan Aluminum Inc., Russelville, Ky. He holds a BS in mechanical engineering from the Milwaukee School of Engineering and is a registered professional engineer in New York and Wisconsin.

The need for change

Much debate over the years has revolved around how maintenance should be measured. There are various theories, but in essence most of the debate concerned how to measure the end results of what was accomplished.

Common measures include maintenance cost/unit output, cost as a percent of replacement value, and equipment uptime. The debate continues, but it may focus on the wrong time frame; all these measurements concern themselves with "outcomes," or after-the-fact measurements.

Most current accounting and measurement methods were developed 70-80 years ago; little has changed about how effectiveness is reported and measured.

But times have changed significantly.

There are three primary reasons why new performance measures are required:

- Traditional accounting and measures are no longer relevant to a company moving toward a world-class plant environment.

- Customers require higher standards; competition is pressed.

- Management techniques and technologies used in plants are changing significantly.

The most compelling reason for change is that these measures are based on lagging indicators, which are after-the-fact results, unchangeable once the measurement time period is complete. Additionally, many decisions are made on the shop floor and the old high level lagging measures are inadequate.