Asia leads world in refined-product demand growth

Asia, one of the world's leading consuming regions, has been the biggest contributor to the worldwide petroleum demand explosion during the past year. The increase in demand is the main reason for the current state of petroleum markets, which is characterized by high prices and extraordinarily wide light-heavy product differentials.

Asian petroleum product demand growth should average about 600,000 b/d/year during the next few years. The high growth experienced in 2004 is probably unsustainable from an economic point of view. For refiners, the growth rate would be difficult to accommodate in the long term.

In 2004, increased refinery utilization has accommodated the rise in Asian petroleum demand. This has brought some fairly inefficient capacity into production and led to higher refining margins. The Asian backlog of surplus capacity is nearly exhausted, however. If growth remains at the feverish 2004 level, shortfalls in refining capacity could emerge.

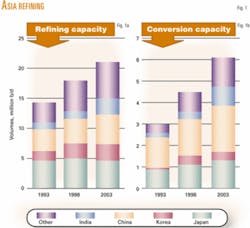

Fig. 1 shows Asian refining capacity during the past decade. Asia has added more than 5 million b/d of crude capacity and about 3 million FCC equivalent b/d of conversion capacity since 1993.

Most of this capacity was committed in 1990-97, although some capacity was installed through about 2000. Newer installations include Reliance Industries Ltd.'s massive Jamnagar, India, refinery; Formosa Petrochemical Corp.'s plant in Taiwan; and new refinery sites owned by majors Royal Dutch/Shell and Caltex Corp. in Thailand, and Petroliam Nasional Bhd. (Petronas) in Malaysia.

Since 1998, few companies have announced plans for new projects, and none for grassroots complexes.

Asia's petroleum future is the key to the future of the global petroleum markets. Compared to other regions of the world, petroleum growth in Asia will be the most difficult for governments to control. Asian petroleum growth is rising in step with the region's rapid economic development; many countries are achieving sufficient wealth such that private automotive transportation is attainable for a large segment of the population.

China's emergence as an economic power is both the greatest boon and the greatest threat to Asian economies and petroleum markets. If China continues on a rapid growth path, spillover economic growth will benefit all Asian countries. If China stumbles, however, then continued regional growth will be more difficult.

Four countries—Japan, China, South Korea, and India—dominate Asia's petroleum demand. They account for 70% of the region's petroleum demand. Smaller consuming nations are still important and some are rapidly growing.

Astute Asian refiners are considering installation of more conversion processing capacity. Chinese refiners have the greatest opportunity to increase crude capacity. Many Asian markets require more sophisticated hydroprocessing and desulfurization to produce cleaner fuels and process less-expensive sour crudes.

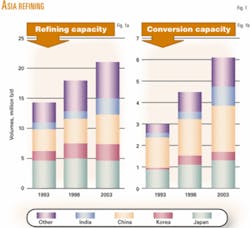

Fig. 2 shows the light-heavy product differential, measured as the difference between diesel fuel and high-sulfur fuel oil in Singapore. After hovering around $3-5/bbl during most of 2000-03, the light-heavy differential has increased to more than $25/bbl, far greater than what is needed to justify new conversion capacity.

Japan

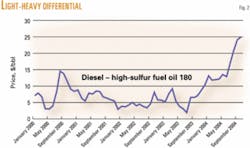

Japan consumes the most petroleum in Asia, around 4.8 million b/d. Demand growth there is growing slowly. Japanese petroleum demand has resumed an upward trend during the past year partially due to transient reasons and partially in a more sustainable way.

For the past decade or more, Japan rarely experienced economic growth greater than 1%/year. Energy demand mirrored economic activity, which was nearly stagnant. Japan substituted LNG and nuclear energy for petroleum in the power sector during this time.

The Japanese economy has recently stirred from its slow growth. Japanese stock markets have risen and economic growth is more than 4%/year. Japan's economy will grow at more than 4% in 2004 and 2-3% in 2005. Japanese industrial production is up more than 9% since last year and unemployment is down.

Renewed Japanese economic activity has triggered a renaissance in petroleum demand, in both transportation and industy (Fig. 3). The renewed demand could continue in the medium term if economic momentum persists.

Since 2002, the Japanese power sector has had a difficult time. That year, Japanese regulators discovered improper maintenance and recordkeeping irregularities at many nuclear power plants. These discoveries led to widespread nuclear plant shutdowns to allow for thorough inspections.

Japanese utility companies were forced to use hydrocarbon fuels to maintain power production levels. LNG and certain crude grades filled this demand surge. Major Japanese utilities can burn low-sulfur crudes, which typifies many Asian grades, but principally the low-sulfur Indonesian crudes such as Minas and Duri. Fig. 3 does not include this demand.

The issues surrounding nuclear energy seem persistent, but the country will resolve the problems eventually and start up the existing nuclear power plants.

Many of the power-generation plants used during the nuclear outage are obsolete, low-efficiency, fuel-oil-fired plants that are normally are held in reserve. The nuclear outage was so widespread that these plants had insufficient capacity to supply peak summer power loads. Regulators are therefore willing to allow plants to resume production as maintenance and inspections are completed.

After the nuclear plant issues in Japan are resolved, utility fuel oil and crude consumption will return to normal levels and continue the downward pace they have been on for the past 2 decades. Japanese demand for bottom-of-the-barrel products will abate, which will lower the light-heavy differential.

Japan's refining industry will continue to be a model of energy efficiency. Product demand growth will be below 1%/year for the medium term after nuclear issues are resolved. Japanese refining capacity will therefore suffice for the medium term.

The Japanese refining system will continue in a state of oversupply. Japanese refiners have sought greater efficiencies through both intercompany "tie-ups" to optimize the distribution system and also by closing some inefficient, redundant facilities.

It is improbable that Japan's refiners will invest significant capital beyond what is needed for clean-fuels programs. Clean-fuels investments will be limited because most Japanese refiners can use revamps of existing units to comply with specifications.

Japan is leading the region in clean-fuels specifications and environmental programs. Japanese gasolines are limited currently to 100-ppm sulfur; a new specification of 50-ppm sulfur will take effect next year. Diesel fuel in Tokyo has a 50-ppm sulfur limit, a specification that will apply nationwide in 2005. Purvin & Gertz expects further restrictions by around 2008, which will limit the sulfur in both products to 10 ppm.

Kerosine has been spared low-sulfur requirements in most markets except for Japan, where it must meet an 80-ppm sulfur specification. Most Japanese kerosine demand is for residential and commercial use for which the strict specification applies; many suppliers have adopted an even more stringent 50-ppm sulfur specification for marketing reasons.

China

China has the highest growth rate for petroleum and also for many other commodities such as steel, non-ferrous metals, petrochemicals, etc. Chinese demand growth is consistent with the spectacular economic growth during the past decade.

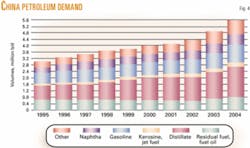

China's petroleum product demand had grown to nearly 5 million b/d in 2003 (which does not include the enormous increases in 2004) from about 3 million b/d in 1995. China regularly reports GDP growth greater than 9%/year and many economists hope for a "soft landing" resulting in growth closer to 7%/year, a figure that would cause envy in just about any other country.

China poses difficult and unique problems for forward analysis. Chinese statistics are notoriously unreliable; the most ardent China watchers believe that reported GDP might err by several percentage points or more. Even the Chinese government has conceded the inaccuracy.

In addition, the direction of error is irregular. There is some indication that the recently reported 9%/year growth figures understate economic performance. And there have been episodes when reportedly small downturns may actually have been far greater.

China government control of the economy is blunt; Chinese regulators lack the fine controls available to European or North American governments. Although Chinese central planners are trying to slow the economy presently, their ability to hit a given growth target is far from certain. There is the risk that regulators' efforts may lead to a far more severe downward correction than that desired.

Historically, dirty-burning coal has supplied most of China's energy, which has contributed to bad environmental conditions in many Chinese cities. Chinese regulators understand the need for cleaner air and are seeking to steer demand to mitigate environmental problems. Parts of China's clean-air program call for relocating some industrial facilities into more remote areas and also for substituting cleaner-burning fuels for coal.

China is promoting natural gas, hydroelectric, and nuclear power plants as part of its clean-air efforts. That program has been only partially successful. The difficulty is that electricity demand has grown far more rapidly than supply, leading to shortfalls in major cities. This year China has experienced blackouts and mandatory power conservation measures.

Industrial and commercial power users responded to shortfalls by using small generators that mostly use diesel fuel, which has led to an increase in fuel imports.

As major new power projects start up in the next few years, utility supplies could gain the edge on demand and many of these generator sets could shut down. That outcome, however, is far from certain; if economic growth continues at high levels, the prospect of continued or expanded power shortages looms.

The Chinese private transportation sector is growing rapidly (Fig. 4). Growth in the private vehicle fleet could be as low as 20% this year or it could be much higher.

Gasoline and diesel demand is growing rapidly in step with automotive fleet growth. International automobile manufacturers have opened joint-venture plants in China and want to penetrate the Chinese market to expand sales.

The greatest threat to Chinese petroleum demand is that government efforts to slow economic growth may be too strong and result in a sudden flattening. The lack of fine-tuning controls may have had this effect in the past.

It is possible that China may engineer a soft landing, but there is scant evidence to support this likelihood. Regulators' efforts will more likely result in either inadequate economic cooling or a sharp, but hopefully temporary, downturn.

Chinese petroleum demand will continue to grow, albeit at a more moderate pace than the past year's 15% growth. There may be a year of zero or even negative growth if the economic brakes are applied too hard; but China's potential as an emerging economic power is enough to overcome such factors.

Chinese petroleum refining is insufficient to meet product demand. In the past decade, China has expanded refining capacity about 1.5 million b/d.

China exports relatively low-quality gasoline and imports other products, mostly into the rapidly developing southern provinces. Rapid growth in the past year has caught major refiners, such as China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. (Sinopec) and Petrochina Co. Ltd., without sufficient capacity.

China refiners have renewed their expansion efforts. China's refining system has high conversion capacity with relatively little fuel oil production.

The emergence and persistence of many small, unsophisticated refineries cloud the supply picture. These refineries, mostly in inland locations, account for more than 500,000 b/d of capacity out of a Chinese total of 5.1 million b/d. Chinese policy calls for them to shut down, but product shortfalls are giving these producers extended life and it is unclear when China will achieve its policy goals.

Chinese refiners have experienced more pressure during the period of high crude prices because domestic product prices have not risen as much as crude. Unlike most of the world, China experienced relatively low margins in late 2004.

China will continue to invest in its refining industry. Investments will include the full range of processing, including more crude throughput, greater conversion, and more hydroprocessing and desulfurization units.

China has implemented limited clean-fuels specifications. Since mid 2000, China has enforced a diesel-sulfur specification of 0.2 wt %. Since January 2001, 0.05-wt % sulfur diesel has been available in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. Due to the low sulfur content of local crudes, most diesel sold in China has a sulfur content less than 0.2 wt %.

Due to a relative shortfall of hydroprocessing and desulfurization capacity, Chinese refiners have imported significant quantities of sweet, expensive crudes. Because the less-expensive, and more-available, imports are sour crudes, China refiners will require more hydrotreating capacity to maintain existing sulfur levels.

Hong Kong has adopted stringent diesel sulfur levels, which will probably spread to other major cities before being adopted nationwide.

South Korea

South Korea has long been a major emerging economy. For more than 30 years, South Korea has averaged 7%/year GDP growth and now enjoys a GDP per capita similar to many European nations.

South Korean economic performance is strong currently and industrial production is up more than 10% this year. Although recently China has had difficulties with too much economic growth and Japan has been plagued by too little, South Korea has kept growth in a comfortable zone that avoids the worst problems on both the upside and the downside.

South Korea was heavily hit by the Asian financial crisis in 1997-98. The country had developed with a system of "chaebols," or conglomerate companies, with close ties to government and preferential access to low-cost debt. South Korea's economic situation grew so precarious that the government appealed to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for assistance.

Whereas IMF's solutions were bad for many Asian economies, South Korea emerged from the experience having dealt with many of the most important underlying issues. South Korea must reform potentially destructive practices, but it has made sufficient progress to return to strong economic growth.

Like Japan, South Korea exports significant volumes of refined products to China. North Asia as a whole, as well as much of Southeast Asia, is at risk if China's economy experiences a serious downturn.

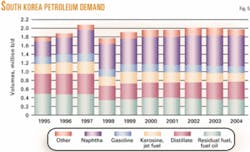

South Korea's energy consumption is reasonably balanced with a slightly higher reliance on petroleum (Fig. 5). South Korea's petroleum demand was growing briskly until the financial crisis when it leveled at about 2 million b/d. Real growth has not resumed, although the mix of products has grown lighter.

South Korea has few energy resources other than coal, which provides less than 25% of domestic energy consumption. South Korea has a strong nuclear energy program that now accounts for the largest share of electrical power generation.

LNG supplies South Korea's natural gas demand. That market has been opened to competition, which has resulted in a new LNG terminal being built on the east coast to supply industrial consumers.

South Korea's power sector still consumes about 100,000 b/d of fuel oil that is subject to displacement by alternatives.

South Korean refiners experienced poor margins until 2003. Domestic refining margins reflect international levels; when Asian margins rose in 2003, South Korean refiners also enjoyed the higher margins.

Large refineries with limited downstream processing characterize the South Korean industry. South Korea has five refineries with about 2.6 million b/d of capacity. The limited downstream processing capability hurt some refiners during 1998-2002. One refiner, Inchon Oil Refinery Co. Ltd., went bankrupt and was purchased by Sinochem Corp.

Due to the higher margins, South Korean refiners are operating at higher utilization levels, around 90%. Proximity to Chinese and Japanese markets is an advantage for South Korean refiners.

New investments are likely for South Korean refineries in the form of more conversion, hydroprocessing, and desulfurization capacity. Currently, South Korea has no plans to install additional crude capacity.

India

India has a growing demand for energy that will be supplied from various sources. India has a significant nuclear energy program and significant crude and natural gas resources, including undeveloped discoveries in the Kakinada Basin off the east coast.

India both suffers and benefits from the various forms of government involvement in the energy sector. Government policies, designed to promote self-reliance and economic growth, occasionally have unintended consequences for investors.

The government remains highly interventionist in the refining sector, which leads to some centrally planned crude allocations and other forms of market distortions.

Private industry has also benefited from government policies. Differential tariffs favor domestic refining and have contributed to Reliance Industries' success in becoming a major supplier of refined products in India and Asia. Reliance's high-conversion Jamnagar refinery has a capacity of 540,000 b/d on a site that had no refining in the mid 1990s and is linked into downstream petrochemical processing.

Other companies such as Essar Oil Ltd. seek to emulate Reliance's example.

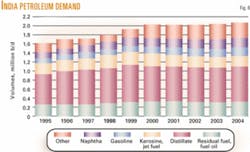

India has not experienced the explosion of demand growth that China has. Although economic growth is strong at 7%/year and higher, energy demand growth is relatively slow (Fig. 6).

The industry is competitive and major companies are planning new investments to expand supply in growth areas. India's product demand grew to about 2 million b/d in 2000, from about 1.6 million b/d in 1995, but has stalled at that level with demand heavily skewed toward diesel.

Other Asia

Japan, China, South Korea, and India account for about 14 million b/d of petroleum product demand. The constellation of smaller countries such as Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and Pakistan comprise another large tranche of petroleum demand, about 5 million b/d.

Those countries as a group have re-entered a growth mode. As a group, all those countries are progressing toward gas substitution for oil in the power sector (Fig. 7).

Most other Asian countries are relatively self-sufficient in refined products. Many of these countries were economically damaged by the financial crisis and are still emerging from it. In general, they are benefiting from Chinese economic growth and remain vulnerable to outside economic shocks. With the notable exception of Indonesia, most of these countries have reasonably transparent petroleum systems and refiners that have exposure to market pricing.

Refining in the smaller Asian countries is experiencing resurgence due to higher profitability. In the near future, there will be no significant refinery expansions, but many refiners will respond to strong cracking margins by investing in new conversion capacity.

Asia's petroleum industry is still vulnerable to slowdowns in China's economy. If China remains on a strong growth track, then that growth will benefit other Asian economies.

Asian refiners' greatest prospects are capitalizing on trends, such as increased demand for lighter fuels, to install conversion projects. These projects create opportunities not only to increase product values, but also to reduce crude costs and find a better product mix for the changing Asian marketplace.

The author

John H. Vautrain is vice-president and director for Purvin & Gertz Inc., Singapore. Before joining Purvin & Gertz in 1981, he worked for Phillips Petroleum Co. and Union Carbide Corp. Vautrain was manager of Purvin & Gertz's Long Beach, Calif., office 1987-2000. Elected director in 1997, he has been based in Singapore since 2000. His Asian consulting activities include crude marketing, petroleum refining, LPG, natural gas, and LNG. Vautrain holds a BA in chemistry from the University of Texas and an MEng in chemical engineering from the University of Utah. He is a member of the International Association for Energy Economics, SPE, and AIChE.