Ethanol 101

Connecticut, New York, and California are working to remove the gasoline additive methyl tertiary butyl ether from the gasoline blending pool and replace it with fuel-grade ethanol.

The Oxygenated Fuels Association (OFA) thinks that's a bad idea and recently said as much to the US District Court of New York. OFA contends that replacing MTBE with ethanol would harm air quality, worsen purported global warming, and lead to higher gasoline prices (OGJ, Dec. 8, 2003, p. 28).

But Dick Sterrett, a lifelong farmer, begs to differ. Sterrett is CFO at Western Plains Energy LLC, a private company currently building a 30 million gal/ year ethanol plant in Gove County, Kan. To begin with, he said, a corn field is a carbon dioxide trap, digesting CO2 as it grows. The CO2 produced during ethanol manufacturing can be captured, compressed, and sold for use in carbonated beverages or to flash-freeze food products. His answer to the charge that ethanol's higher Reid vapor pressure could cause an increase in smog precursors during hot summer months: "No, it won't." Ethanol currently meets all government rvp standards, Sterrett said. Well, what about those projected higher gasoline prices?

"The US exported 19% of its corn crop in 2002," he said, "and we subsidize those exports with tax dollars. Why not use some of that ourselves?"

Sterrett contends that diverting some of the export subsidy dollars to expansion of US ethanol capacity could offset any marginal increase in gasoline price.

Unlike oil, corn is renewable. Making ethanol from corn is a fairly efficient process—although critics claim it consumes more energy than it produces—because markets exist for coproducts from its manufacture.

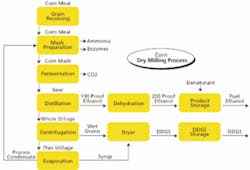

An explanation of the process method is necessary to illustrate this point (see chart). In a dry milling process, harvested corn is passed through hammer mills that grind it into a fine powder. The resultant meal is mixed with water and alpha-amylase and is passed through cookers that liquefy the starch. The high temperature also eliminates bacteria.

The mash from the cookers then is cooled, and gluco-amylase is added to convert the starch to dextrose. An addition of yeast ferments the dextrose to produce ethanol and CO2. In a batch process the mash stays in the fermenting vat for about 48 hr to make what the old-time bootleggers of Tennessee and Kentucky called "corn squeezins." Today, of course, we call it beer.

The beer is sent on to a multicolumn distillation system, and the alcohol is separated from the solids and water. The 190 proof alcohol is removed at the top and the residual mash, or stillage, is transferred to the coproduct processing area.

The alcohol is dehydrated via molecular sieves to remove any residual water, and the result is 200 proof anhydrous ethanol. This ethanol is "denatured," at the request of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, with a small addition of gasoline to make it unfit for human consumption.

Darned spoilsports.

The leftover stillage retains all of the corn's protein and nutrients and is a highly valued livestock feed ingredient—making ethanol production virtually a no-waste process.

As a fuel additive, ethanol readily mixes with gasoline at the rack. The mixure, typically 10% ethanol and 90% gasoline per batch, is known as E-10 unleaded.

By the numbers

So what does it take to produce 30 million gal/year of ethanol? One bushel of corn produces nearly 3 gal of ethanol for blending. Western Plains Energy will be processing 40,000 bushels/day of corn to produce over 100,000 gal/day of 200 proof alcohol. Some 250-500 acres of feed grain production will be needed—thus creating the aforementioned CO2 sink.

The plant also will produce 90,000 tons/year of wet distilled grains. Luckily, there are 2.5 million (and counting) cattle to feed in Kansas.

In the future, the coproduced CO2 can be purified, compressed, and sold. However, this process is extremely energy-intensive and will not be available initially at start-up in early 2004.

Another hurdle to widespread use of ethanol is the fact that it cannot be transported by a nondedicated pipeline because the smallest amount of water in a pipeline will contaminate the ethanol and require expensive redistillation. To avoid this problem Western Plains will send out its production via truck or the nearby Union Pacific railroad.