High NGL, natural gas prices make processing margins more volatile

A substantial shift in natural gas prices has increased returns for gas producers and provided incentive for increased drilling and well workover activity. Although natural gas and NGL prices have increased, NGL price movements have not precisely mirrored natural gas prices, a situation that has resulted in increased processing margin volatility.

In the past, gas producers commonly lamented the gas "bubble" and worried that North American gas demand would never catch up with a seeming ocean of available gas supply.

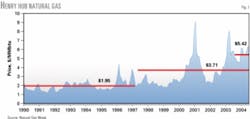

Currently, the tight gas supply-demand balance is causing the longest sustained period of relatively high spot gas prices since the industry was decontrolled in the early 1990s (Fig. 1). The monthly average spot price for natural gas has increased nearly threefold since the early 1990s.

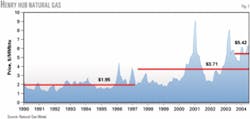

Fig. 2 compares trends in spot natural gas, ethane, and mixed-NGL prices since 1995. Short-term changes in these prices have not necessarily moved in the same direction or netted equivalent changes in margin. The relative independence in price movements challenges gas processors who are price takers in the market.

Processing profitability

Muse, Stancil & Co. previously provided (OGJ, May 21, 2001, p. 54) a summary of the bases for gas processing profitability measures that are now published monthly in the OGJ statistics section. One key measure of gas processing profitability is the net operating margin.

Fig. 3 summarizes historical net operating margins for hypothetical US Gulf Coast and Midcontinent gas processing configurations.

The net operating margin accounts for the overall cash margin before taxes and is defined as the net value of the recovered NGL at the plant tailgate less plant fuel, direct cash operating expenses, and gas shrinkage. Product prices are adjusted to represent plant tailgate realizations based on typical regional transportation and fractionation fees.

The net margin does not include an allowance for depreciation or for return on invested capital.

Since gas prices first spiked significantly at yearend 2000, net gas processing margins have been highly volatile and decreasing overall. As a result, the hypothetical US Gulf Coast plant has realized an average net margin loss of $0.03/inlet Mcf since late 2000, compared to a positive average margin of $0.06/inlet Mcf for 1990 through late 2000.

The hypothetical Midcontinent plant has fared better since late 2000, realizing a positive average margin of $0.04/inlet Mcf compared to an average net margin of $0.22/inlet Mcf for 1990 through late 2000. In both regions, gas processing profitability has declined since 1990.

Economic implications

The low-margin environment has varying economic implications, depending on the corporate structure and contract portfolio unique to each processor's operation. Corporate structure influences the level of exposure to gas margin risk for any individual company, whereas the makeup of individual contract portfolios influences the ongoing degree of margin exposure for specific plants or processing systems.

Corporate structure

Merchant gas processors own and operate gas gathering and processing assets in order to profit from processing gas for other parties.

Producer-processors, by contrast, own equity gas production as well as gas gathering and processing assets and may also provide services to other producers that operate in the same geographic region. A single producer or a consortium of producers operating in the same geographic region can own producer-processor assets. Producer-processors are primarily in the business of developing and monetizing natural gas production and generally view gas processing as a necessary step required to market equity gas.

Merchant processors and producer-processors are both exposed to gas processing margins. Merchant processors, however, have traditionally relied on the gas processing margin for a significant portion of their revenues; the primary revenue source for a producer-processor comes from the sale of equity production.

When natural gas production contains significant levels of contaminants such as H2S or CO2, producer-processors may experience relatively higher levels of processing margin risk. This is because the contaminants dilute the hydrocarbon gas and result in higher processing costs.

In general, producer-processors are naturally hedged against low processing margins that result from high gas prices because the higher gas revenues offset the lower margins. In the current environment of relatively high prices for natural gas and relatively low gas processing margins, merchant-processors are more affected by the low margin environment than are producer-processors.

Contract portfolios

The makeup of any facility's gas processing contract portfolio is key to assessing that facility's level of exposure to gas processing margins.

Three general types of contracts typically account for most of a plant's portfolio: fixed-fee contracts, percent-of-proceeds (POP) contracts, and keep-whole contracts.

Fig. 4 shows that each of these contract types provides a different allocation of the gas processing margin risk between the producer and processor.

In fixed-fee contracts, the producer pays the processor a fixed fee for processing services, usually on a per-Mcf basis. Because the processor receives a negotiated fee and takes none of the products as compensation, the producer bears all of the risk of the gas processing margin.

Gas processors could minimize margin risk with a portfolio of only fixed-fee contracts, but such agreements are traditionally used for ancillary services such as gathering, compression, or conditioning (dehydration, CO2 removal, etc.) rather than as compensation for the recovery of NGL.

Keep-whole contracts require the processor to return enough processed gas to the producer to equal the total btus of raw gas delivered at the plant's inlet. In this type of contractual arrangement, the processor bears all of the processing margin risk, which allows the producer to monetize gas without realizing the economic impact of processing.

This type of arrangement is popular with smaller producers that focus primarily on production operations and are not fully integrated gas marketers. In the past, gas processors would routinely contract for keep-whole processing to maintain or enhance gas throughput when margins were robust.

Since the unexpected gas price spike of 2000-01 when keep-whole contracts were associated with significant cash losses, most processors have worked to minimize exposure to these contracts.

In POP contracts, the processor and producer share the processing margin risk because revenues for both parties are generated from selling a share of the products.

The processor expects that selling a portion of the products will cover the entire plant's cash operating costs and provide for the return on, and return of, capital. For the producer, selling the products represents the monetization of equity gas production and should cover the amortization of finding costs, production costs, as well as the operating costs for fuel, volume shrinkage, and volume losses associated with processing.

The contract portfolio of a single gas processing plant typically contains a mixture of contracts, including hybrid versions. NGL recovery services are typically included in POP-type contracts; however, the actual terms and conditions for processing vary from sharing all the products to sharing only NGL and often include additional fixed-fee components for ancillary services.

Some contracts also incorporate more complicated options such as bypassing gas processing intermittently or minimum revenue provisions that incorporate a keep-whole settlement.

The POP terms generally depend on the contract term, volume and quality characteristics of the raw gas, delivery conditions and location of the raw gas, characteristics of the gathering and processing facilities, and perspectives of the producer and processor with respect to future gas processing margins.

A processor can control the margin exposure in each gas processing plant by actively managing the plant's contract portfolio. Processors, for example, can terminate or refuse to accept keep-whole contracts, shift as many of the provided services as possible to fixed-fee terms, and negotiate POP-sharing percentages with margin volatility and anticipated short-term margin losses in mind.

Innovative processors can also try to negotiate revenue floors to limit cash losses due to unexpected, extended

periods of market disruption. As previously discussed, producer-processors have an inherent natural hedge to low margins. The total margin exposure for an individual producer-processor, however, depends on the volume of third-party gas processed and the associated contract terms for processing.

Margin outlook

The gas processing margin outlook depends on future prices for natural gas and NGLs. Natural gas prices in the US are historically determined by regional or local supply-demand factors, although future increases in LNG will impact the fundamental pricing bases.

Supply and demand for petrochemical feedstocks primarily determine NGL product prices, which are related to crude oil prices through the pricing of comparable crude-oil derived products that can substitute for NGLs.

In the short-to-medium term, natural gas and NGL prices will continue to move independently of each other. In the longer term, however, these prices will become more interdependent because the long-term driving factors for demand growth for natural gas and NGL are similar, namely economic growth and the demand for fuel and petrochemical feedstocks.

High natural gas prices are the primary reason for the recent overall decline of natural gas processing margins. In the short-to-medium term, the outlook for natural gas prices remains high because the US supply-demand balance will remain tight.

Current natural gas prices have created incentives for increasing the amounts of LNG to move into the US; LNG imports have increased to more than 500 bcf in 2003 from 230 bcf in 2002.1 US import capacity capabilities and the availability of LNG worldwide, however, are currently limited, thus reducing the short-term impact of LNG imports on overall US gas prices.

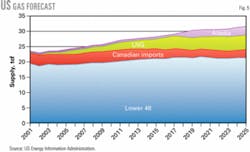

In the longer term, Lower 48 states' gas production will remain relatively flat and demand for natural gas will to continue to increase. The incremental natural gas supply needed to meet increasing US demand will come from increased imports of LNG and, longer term, from the development of Alaska gas for the North American market.

Fig. 5 shows the US Department of Energy's Energy Information Administration's forecast gas supply outlook. As LNG import capacity expands and additional world LNG supply becomes available, US natural gas prices will be more closely linked to the world gas market and ultimately to the cost of incremental worldwide LNG supply.

The industry consensus seems to indicate that the long-term cost to develop and bring LNG to the US market will average $3-4/MMbtu, which will result in a decrease in long-term gas prices.

The outlook for US NGL product prices depends on the outlook for crude oil prices and the expected derived demand for NGL from the US petrochemical industry.

Crude oil has recently been trading at all-time market high prices due to the tight balance between short-term demand and supply and the threat of supply disruptions. The premium due to the threat of terrorism, war in the Middle East, and political and commercial disruption of Russian, Venezuelan, or other foreign supplies will likely continue in the short term to medium term until additional worldwide crude oil supply becomes available or demand declines.

The US petrochemical industry must remain competitive with foreign products that are manufactured with lower-cost fuel and feedstocks. US petrochemical producers have been, and continue to be, hurt by high US natural gas prices.

In the short-to-medium term, high natural gas prices will limit the construction of new US petrochemical plants; expansions to meet worldwide demand will come from producers outside the US. Moderating this impact is the high proportion of outside-US petrochemical production manufactured from crude-oil-derived naphtha feedstocks and the corresponding relationship of NGL prices to crude oil.

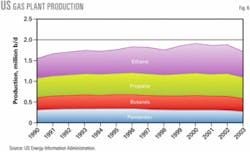

Fig. 6 shows that historical US gas plant production of NGLs may have peaked in 2000.

In recent years, higher NGL recovery efficiencies have resulted in more NGL production despite flat or declining volumes of processed gas. Increased NGL recoveries are due to the closure of older, less-efficient plants and technology upgrades in existing facilities. This efficiency effect will moderate in the future due to the lack of new opportunities to consolidate or improve operations.

A greater proportion of future gas production will come from unconventional gas sources, such as coal-seam gas, that contain less NGL than conventional US gas production.

The ultimate disposition of NGLs associated with Alaska natural gas production and the possibility of some NGL recovery from LNG imports may offset decreases in available NGL supplies.

Given the outlook for the natural gas and NGL markets and the independent movement of prices in the short-to-medium term, the future of gas processing margins will continue to be highly volatile. Higher natural gas prices in the short-to-medium term will be somewhat offset by relatively high NGL prices but will continue to produce a relatively low margin environment.

Commercial considerations

Gas producers and processors face a difficult task: to maximize current profit in a volatile market and to plan for ongoing processing with uncertainty about market prices.

Perceptions of the current and future states of the operating environment will impact contract negotiations, plant operations, and contract settlement.

Contract negotiations

Successful negotiation of contract terms is based on alignment of the processor and producer with respect to future gas processing margins. Negotiations should account for all of the costs that the producer and processor will ultimately bear including fuel, expected losses, ancillary service costs, and marketing costs.

Processors may also seek gas-volume commitments, long-term processing commitments, and retention of processing flexibility, which will allow them to transfer gas to unspecified facilities for processing.

In exchange for concessions on costs and processing commitments, producers may ask for processing flexibility—such as the ability to bypass processing in negative-margin periods, reject ethane from the NGL stream, or fix NGL recovery efficiency.

Producers may also strive to control total gas processing costs by limiting fuel and loss allocations, specifying gas processing facilities utilized for processing, or retaining the right to terminate the contract in the event of a change in ownership or operations.

Although contracts are usually only ratified by the parties after careful negotiations and legal reviews, it is not uncommon for disputes to arise about issues that are either not well documented in the contract or not well understood by one or both of the parties. Disputes are often addressed through the audit process, but sometimes more-extensive legal action is required.

The best way to avoid a contract dispute is to spend adequate time in the negotiation process, understand and evaluate all of the contract alternatives, and finalize the deal with a well-written and properly documented contract.

Plant operations

In a dynamic margin environment, processing operations are affected because producers take advantage of contract flexibility to attempt to maximize short-term profitability. Processors continually adjust operations to respond to producers' processing elections given the myriad of negotiated terms within the overall contract portfolio. This complicates the management of the processor's own profitability.

If allowed in the contract, processors may also elect to make "paper processing adjustments," rather than actual changes in plant operations to ensure that the producers' processing requirements are met.

Increased pressure on gas processing margins and the unpredictable nature of margin volatility during the last several years has also resulted in further plant consolidations. Although less excess gas processing capacity does effectively reduce overall gas processing costs, processors and producers are not always aligned in terms of the benefits of plant consolidation.

When plants are shut down and gas is transported farther for processing, producers often bear the burden of increased fuel and losses while processors reduce their cash operating costs, limit their capital base, and reduce future commitments for maintenance capital.

Unless producers benefit from increased plant efficiencies, operating flexibility, or reduced processing costs (higher producer POP percentages, lower fixed fees, etc.), producers may actually end up paying more for gas processing due to plant consolidations.

Contract settlement

Processors must ensure that the settlement for gas produced from each well under every contract conforms to the contract terms and conditions each month.

This settlement should account for all of the gas received into the system, consumed in the system, and delivered out of the system as commercial product. In addition, processors ensure that all costs that can be allocated to producers under contracts are accounted for and properly allocated. Cost control is one of the keys to margin management for the processor.

Because of the operational complexity and the hundreds of contracts included in a single plant or system settlement in a single month, producers often are overwhelmed by the settlement process and frustrated by attempts to monitor or track the trends in their gas settlement.

It is not uncommon for errors in gas settlement to occur and, therefore, producers should closely follow monthly gas settlement and ask questions to clarify understanding of any changes in the process.

Reference

1. "US LNG Markets and Uses," US Energy Information Administration, Washington, June 2004.

The authors

Susan L. Starr ([email protected]) is a principal with Muse, Stancil & Co., Dallas, and has more than 15 years' experience in the energy industry. Her work encompasses financial analysis, valuation, market analysis, and damage assessment in the gas processing, transportation, and refining and marketing sectors. Starr holds BS and MS degrees in chemical engineering from Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, and an MBA from Southern Methodist University, Dallas.

Lesa Adair ([email protected]) is a vice-president and director of Muse, Stancil & Co. She consults on issues related to valuation, damage assessment, market evaluation, and transactional due diligence in the energy sector. With more than 20 years' experience in the industry, she frequently assists in dispute resolutions and advises clients on mergers, acquisitions, project development, and investment decision-making in the transportation, processing, refining, marketing, and electrical-generation sectors. Adair holds a BS in chemical engineering from Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, and an MBA from Southern Methodist University, Dallas.