Special Reports: China, India lead growth in Asian refining capacity

Asian refining capacity continues to grow rapidly despite the effects of a suffering global economy. China and India especially are fast-growing economies that are leading demand growth for transportation fuels.

This article reviews the factors that influence refined-product demand growth in Asia and the future of refining projects in Asian countries.

Asian refining demand

East of Suez refining continues to increase even as Atlantic Basin refiners feel the effects of a global recession. For the past decade, most global petroleum demand growth has occurred East of Suez as Asian economies grow rapidly. Although economic signals are not certain, Asian petroleum demand and refining will continue to expand in the next 5 years.

Asia consists of many different economic and political systems. Some Asian economies continue to be heavily centrally planned and others are based on free markets. Politically, one-party systems continue in countries like China and Vietnam while turbulent and often multi-party democratic coalitions govern India.

In petroleum, national oil companies or other dominant state-run enterprises supply many countries such as China, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam. Alongside the state-run companies are innovative private-sector enterprises.

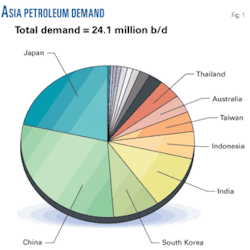

Four countries dominate Asian petroleum demand: China, Japan, India, and South Korea (Fig. 1).

Economically, the Asian economies as a group are healthier than their Atlantic Basin counterparts.

Although 2008 was a relatively poor year by Asian standards, substantial positive GDP expansion will continue in key economies. Many Asian economies have healthy reserves that can be called on to soften the indirect blow of the global economic downturn as China has announced.

Chastened by the disastrous 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the banking systems and their regulators have been more cautious than their American and European counterparts. Asian banking systems have been spared the worst of the subprime mortgage crisis and related credit default swaps problems.

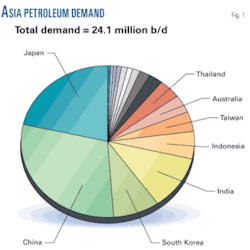

China and India stand out as examples of diesel oriented, fast-growing economies (Fig. 2). China and India account for nearly 10 million b/d of demand. Both these populous countries have healthy economies, expanding on the order of 7-11%/year of GDP, and low penetration of private sector automobiles.

An important factor in transportation fuel demand growth in India and China is a growing private-sector automotive fleet. High GDP growth translates directly into higher GDP per capita.

Income disparities across the economy coupled with rising GDP per capita, large population, and favorable demographics mean that large numbers of persons are entering the middle class each year. Some of those individuals are new purchasers of private sector automobiles each year and begin to contribute more to national fuel demand. That growth of the driving middle class is a far more important determinant of fuel demand than price-induced conservation.

Southeast Asia has many smaller petroleum economies with slower-growing demand. Demand expansions in this region remains positive but low. Many of these countries have experienced considerable reductions due to high petroleum prices even though economic outlook for these countries remains generally favorable by international standards, about 5-7%/year GDP growth.

South Korea is a fairly static petroleum market. Wealthy by Asian standards, the South Korean economy already enjoys high penetration of private automobiles, and the outlook for growth in that sector is low.

Japan is the only sizable shrinking petroleum economy in the region. Japan’s economic performance has been lackluster for more than a decade. Declines in property values and banking sector woes began in Japan in the early 1990s after the speculative bubble of the 1980s. Japanese regulators have mishandled this problem over the years.

The Japanese population has been both shrinking and aging. Birth rates in Japan are below the levels needed to sustain the population and inward migration is discouraged. Japanese regulators take Kyoto obligations toward greenhouse gas reductions far more seriously than their counterparts in Europe, and as a result considerable efficiency gains are coming in an already energy-efficient economy.

Fuel subsidies

Fuel subsidies have been overstated as a trigger for Asian petroleum demand.

In many Asian economies, petroleum pricing is not as volatile or as closely in step with international prices as compared with product prices in the US. There is some degree of cross-subsidization that occurs. For leading economies, however, prices are not very different from international prices.

China has a system of price controls on common consumer fuels. Before crude prices started to rise in 2004, China had a goal of gradually releasing prices from controls. High prices have delayed that program.

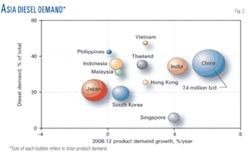

Fig. 3 shows the price track from 2003 for gasoline in South China. Prices have risen throughout that historical period. Most of the time, prices were somewhat below international parity as Chinese authorities often expected that international price rises would be transient, an expectation shared by many observers over this era.

The most serious pricing discrepancies occurred only in 2008 due to the astronomical rise in crude prices. After the more recent price collapse, while Chinese diesel remains under international parity, international product prices have fallen below domestic Chinese prices for gasoline.

In India, the pattern is different and retail gasoline prices have generally been considerably higher than corresponding US prices. Heavy subsidies are involved in determining that price but also heavy taxes. Taxes at the state level far exceed the federal-level subsidy leading to consumer prices that are very high notwithstanding low, controlled retail margins.

In both countries, diesel prices typically are less than gasoline prices. Gasoline is often treated as a luxury item, something purchased typically by the upper social strata. Diesel fuel is treated as a more common fuel, important to commerce and agriculture. Tax and pricing treatment in many Asian countries have the effect of cross-subsidizing diesel fuel somewhat at the expense of gasoline.

Overall, the pricing structure has had relatively little influence on Asian demand growth. The volume of fuel sold at heavily subsidized prices in countries like Malaysia and Indonesia is far less than the volumes in markets with prices closer to or exceeding international parity levels.

China refining outlook

China continues its run of refining expansions and record-setting demand. Chinese demand is heavily oriented to light products and refinery resid production is quite low. Historically, Chinese refiners produced resid in proportions similar to US refiners—about 6.2% of total refinery product volume.

Chinese so-called “teapot” refineries have experienced difficult market conditions during the past year. The term “teapot” refinery is misleading in that many of these plants are sophisticated even if not large by worldwide standards. Some “teapots” have full conversion of heavy feedstocks combined with power production from coke.

The “teapot” refineries are outside the national system that favors CNPC and Sinopec. Consequently, they lack direct access to low-priced domestic crude and also to international crude markets. They are, nevertheless, subject to the same product price controls as the national refiners.

These refiners use residual materials historically from Russia and more recently from the Middle East via Fujairah as feedstocks. Some crude access is achieved through tie-ins with local government entities or by small but favorable deals with CNOOC or the national refiners.

The combination of product price controls and internationally priced feedstocks caused this group of refiners to suffer seriously depressed or negative margins through much of 2008. Recent price declines have eased their situation.

During 2008, the national refiners have been under margin and earnings pressure. The same factors that affected the teapot refiners affect the major refiners particularly on incremental runs of imported crude.

In 2008, leading Chinese refiners were unenthusiastic about high run rates and tended to take extended, more casual shutdowns. The Beijing government made some accommodation to these refiners both in increased product prices but also in the form of direct payments to compensate their refining losses. These accommodations were generally insufficient to offset losses and lacked predictability.

Notwithstanding that, refinery throughput in China has risen and petrochemical profitability has softened significantly since the summer due mainly to the global economic downturn.

Chinese policy for refined products calls for self-sufficiency in major refined products, gasoline, jet fuel, and diesel. These fuels are considered strategic military fuels and the Chinese government is disinclined to allow the country to require regular imports.

LPG and fuel oil are regular import items with much of the fuel oil import volume for teapot refinery feedstocks. Chinese policy favors LPG consumption in the residential-commercial sector as a clean alternative to coal.

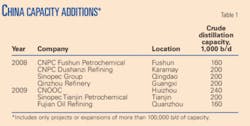

China has been developing many refining projects to supply growing fuel requirements (Table 1). Most of the projects are purely Chinese, although some have foreign joint-venture partners. Chinese interest in joint-venture partners has waned considerably over the years and now is limited mostly to strategic suppliers of crude.

China will continue to follow its policy of supplying strategic fuels from domestic refining. That means China will be an improbable consumer of petroleum products manufactured by export refineries in other parts of Asia or the Middle East. Nevertheless, as supply and demand continue to progress, periods of imbalance will occur when products will be imported, such as in 2008.

China is an unlikely source of major export volumes. It has no comparative advantage in refining. Although China has been an exporter of gasoline at times, it is unlikely the country would install appreciable new capacity oriented to waterborne export markets. Chinese producers will have little effect on the global refining industry other than competition for crude sources.

India refining outlook

India is seeking to become a major new product exporter. India’s petroleum sector is divided between the public sector units (PSU) such as Indian Oil Corp., Hindustan Petroleum, ONGC, and Bharat Petroleum, and the private sector refiners such as Reliance and Essar. Both sectors are growing.

Reliance is in the process of starting up the second train at Jamnagar in Gujarat on the northwest coast of India. Reliance took the step of declaring its existing refinery an “export oriented unit” recently, which has the effect of directing the preponderance of the refinery’s output to foreign markets.

Before then, Reliance had been a supplier to the PSU companies that, as a group, have refining capacity insufficient to supply their retail market volumes. Once the second plant is running, Reliance will have about 1.2 million b/d of high conversion, heavy-crude processing oriented to export markets.

Although Reliance has discussed that the US and Europe are key export destinations, the company has opened marketing offices in Houston, London, and Singapore. Asia may become more important than earlier anticipated now that demand is soft in the Atlantic Basin.

Essar has started a major new refining operation near Jamnagar at a site called Vadinar. Essar has begun refinery operations with a cracking configuration that manufactures conventional fuels.

Essar plans a far more ambitious coking configuration that would become a third major unit oriented to export markets. Thus far, Essar’s effect on global markets has been muted by India’sPSU company refining shortfalls as compared with domestic retail volume.

Long known for lackluster petroleum demand growth, Indian demand has blossomed in the past year despite higher prices. Product prices are generally at or near global levels although the net effect of taxes and subsidies is to penalize the PSU companies that control retail marketing.

Kerosine and LPG are heavily subsidized but other products are not. Development of product demand growth in India, now double digits in some states, is associated with two factors.

First, economic growth has broadened from predominantly services into more manufacturing, infrastructure development, and other more energy-intensive areas. Second, a stubborn shortfall of power has led to brownouts and installation of many private generators to maintain power during times of nonavailability.

Not just factories, but hotels and office buildings have such installations; more private homes have installed such capacity. These small generators are generally diesel powered and significantly contribute to demand. A similar situation contributed to the Chinese growth explosion of 2004.

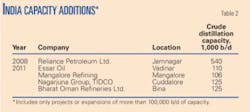

Table 2 summarizes some of the larger refining installations starting up during the next few years. The Reliance project is starting up now and is essentially complete. The Essar project shown is only a small part of a larger project that is scheduled for 1-2 years later.

Table 2 shows several smaller refinery projects that are in PSU companies or that would contribute to PSU supplies via purchase contracts. More projects are still pursuing funding in order to enter firm status.

Unlike China, India will be a major product exporter through its private-sector refineries. The PSU refineries will export residual fuel oil and naphtha but little or none of the key transportation fuels.

Other countries

Singapore continues as a major Southeast Asian export-oriented refining center. Historically, Singapore refiners—Shell, ExxonMobil, and Singapore Refining Co.—have served as swing producers scaling back production in times of poor margins. That role continues, although the refiners as a group have taken steps to improve their economic strength mostly through integration into petrochemicals.

Both ExxonMobil and Shell are affiliated with major ethylene and aromatics complexes in Singapore. The result has been greater staying power in times of weak margins.

South Korea has become an important, market-sensitive swing producer of products through the major refiners: Hyundai, SK, GS Caltex, and S-Oil. SK and GS Caltex are already heavily integrated into major petrochemical complexes.

South Korea is adding greater complexity through conversion processing. These refiners will tend to trim exports of fuel oil and focus more on light products.

Japan, long an inward-looking refining nation through its moto-uri companies, is becoming more outwardly focused. Faced with falling demand for both light and heavy products, the Japanese industry as a whole is reconciled to the need for consolidation and closing uneconomic units. Japan, however, offers the potential for high-value exports.

Japanese refiners have been quality conscious for decades and are accustomed to manufacturing to demanding Japanese industrial specifications. With addition of some new conversion units and, more importantly, improved logistical facilities for loading export cargoes, Japan may become a new exporter of note in the next 5 years. The most likely target for Japanese products will be the US West Coast with its demanding quality requirements and relatively short-haul shipping.

The author

John Vautrain (jhvautrain@ purvingertz.com) is vice-president and director for Purvin & Gertz Inc., Singapore. Before joining Purvin & Gertz in 1981, he worked for Phillips Petroleum Co. and Union Carbide Corp. Vautrain was manager of Purvin & Gertz’s Long Beach, Calif., office 1987-2000. Elected director in 1997, he has been based in Singapore since 2000. His Asian consulting activities include crude marketing, petroleum refining, LPG, natural gas, and LNG. Vautrain holds a BA in chemistry from the University of Texas and an ME in chemical engineering from the University of Utah.