Higher transport costs drive demand for derivatives

Oil tanker freight rates have been driven higher this year by the same forces driving crude oil prices—strong global demand. At the same time, ship charterers and oil traders are using the derivatives market to reduce their exposure to these extreme and highly volatile freight levels.

With the price of oil at 30-year highs, an extra 5-10% added for transportation can be very expensive. But as costly as the freight portion may be, moving millions of barrels of crude from producer to consumer by ship is usually the only option. Increasingly, charterers who hire ships on a regular basis for a single voyage or longer periods are using the derivatives market to reduce their exposure to rises in freight costs.

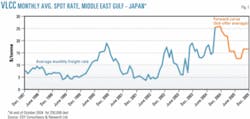

When taking a ship on a single voyage (spot) or longer-term (timecharter) hire, charterers in 2004 have been faced with massive freight costs (Fig. 1). Paying well more than $100,000/day for trading a VLCC (see Terminology box) from the Middle East Gulf to Japan—or around $60,000/day for a VLCC to the US Gulf—has been a feature of the tanker markets for much of the year; even higher levels have been seen so far in the fourth quarter.

By comparison, these rates were about $50,000/day in 2003 and $20,000/day in 2002 for VLCCs trading Middle East Gulf to the US Gulf.

As we near the end of 2004, the general trend for tanker freight costs is much firmer. Record rates are being paid on some of the major routes, supported by very strong oil demand and supply side fundamentals at a time of relatively low US oil stocks and limited fleet growth.

While many shipowners are profiting from the robust growth in oil tanker demand, ship charterers (e.g., oil companies importing oil into the US) increasingly are forced to absorb the higher freight cost for oil or pass it on to consumers. This further inflates the price of what is already a highly expensive commodity.

Freight agreement

This year has seen an unprecedented interest in hedging freight through derivatives; i.e., an agreement made between a buyer and seller today for the future freight rate price of moving bulk shipments from one location to another over a period of time.

A Forward Freight Agreement (FFA) is an over-the-counter (OTC) product traded on the forward price for major trading routes. The concept was first introduced to bulk shipping in 1985 with LIFFE trading and BIFFEX, a weighted basket of freight routes (see Terminology box). Since 1992, individual shipping routes have been traded OTC as cash swaps whereby the trader assumes counterparty risk of default but gains the advantage of settling against a specific route rather than a basket of routes, thereby reducing basic risk.

Use of FFAs has grown very quickly in the dry bulk (coal, iron ore, and grain) trades, largely because the cost of freight as a share of the dry bulk-commodity cargo is much higher than in the case of oil. Hedging the cost of freight, therefore, can make a huge difference to the delivered price when transporting a shipment of coal.

Also, the exposure to freight-rate risk can last for a sustained period because a large component of the dry-bulk business is done on a contract and-or time charter basis, rather than spot voyage. A flexible hedging tool, therefore, is needed for the long-term underlying position.

Freight costs

The use of derivatives has been slower in the oil tanker markets partly due to the lower share that freight comprises when oil is being shipped. This situation is steadily starting to change, however, and now most of the oil majors have joined independent oil traders in managing the upside risk of high freight cost through trading FFAs.

For example, in May 2004 it was possible to lock in freight costs for trading 250,000 tonnes of crude from the Middle East to Japan for the rest of the year at about $11/tonne. Today, if a trader wants to do this with the same cargo, it would pay about $36/tonne (Fig. 3). To the big oil traders and tanker charterers, the ability to manage this huge upside freight risk—worth millions of dollars—is quite attractive.

Historically, the cost of freight for crude oil (i.e., chartering a ship) rarely comprises more than 5-6% of the cost of cargo. On various occasions in 2004, however, freight costs have risen to around 15% of the price of the crude oil (Fig. 2). The trend has been even more pronounced in the trading of refined fuels.

The record freight costs, as well as the further deregulation and liberalization of the global energy business, have added some impetus to the tanker FFA markets, as oil traders hedge their freight exposure in a similar way to which they cover their physical position on each barrel of oil they trade using the derivative market. This is leading to an increasingly active role in the FFA market for oil majors and traders because it can make all the difference to arbitrage opportunities and profit margins. Joining them are banks and other financial institutions that want to trade on the more liquid and volatile routes—sometimes on speculation and sometimes in conjunction with their underlying oil trading positions.

For the most part, tanker owners have been slower to enter the FFA market, with the majority instead putting ships out to the market for a specific period of time when a downturn in earnings is expected, thus helping reduce the downside risk of lower spot rates.

When the timecharter business is right, shipowners can ensure a steady income even if spot freight rates plunge. Such period coverage, however, cannot always be arranged at a preferable price or ideal time, nor flexible to change if the tone of the market shifts. This is why some shipowners have turned to the FFA market to sell a forward position and keep their ships on the spot market.

If spot freight rates fall, earnings also drop, but a paper position(having bought or sold a futures contract) in the market can ensure that (some of) this loss is offset by money made on FFAs. Conversely, if the owner calls the market wrong and sells a route for a future period which actually ends up rising, the tanker owner will 'lose out' on the FFA, but will be able to keep his ship on the high spot market, thus offsetting his paper position.

Income predictability

Shipowners who are publicly held (compared with privately owned and controlled companies) are increasingly active in tanker FFA trading, mainly because the shipping derivative market offers the opportunity for more predictable and steady income flow rather than a boom-or-bust cycle. And banks increasingly view the FFA market as a means to hedge any downside in earnings while owners look to present a more secure investment for their lenders.

For the rest of 2004, we project that the upside risk and volatility for crude and product freight rates will dominate the picture as oil demand and tanker demand strengthen in line with seasonal trends and very firm economic conditions. The outlook for 2005, however, is for a softening in average freight levels due to the expansion in the tanker fleet and slower global economic growth, leading to lower oil and tanker demand growth. Therefore, we expect more interest in the tanker FFA market coming from shipowners who wish to reduce their exposure to any downturn in freight rates.

Considering the vulnerability of tanker freight rates to nonfundamental factors—such as oil strikes, severe weather, and security scares—freight rate volatility is likely to be a prevailing feature of the tanker sector. This will provide opportunities to FFA traders with or without an underlying position in the oil freight markets.

The author

Louisa Follis (research@ ssy.co.uk) is SSY's principal tanker market analyst, covering research, analysis, publication, and presentation of oil and tanker markets for a wide range of clients including ship owners and charters as well as oil and tanker industry organizations. Before joining SSY, she worked as a shipping journalist for 7 years in Singapore, the US, and the Middle East. Follis holds an MSc in shipping, trade, and finance from City University, London.

Terminology

Large crude oil tankers

- Ultralarge crude carrier (ULCC), >320,000 dwt

Very large crude carrier (VLCC), 200,000–319,999 dwt

Suezmax, 120,000-199,999 dwt

Aframax, 75,000-119,999 dwt

Elements of tanker FFA

- An agreement today to buy or sell a Worldscale (WS) freight rate at a certain level (contract price) for pricing out (settlement price) over a future period (month/quarter/calendar), i.e., cash settled on difference between contract price and settlement price.

Settlement price based on average of whole month freight assessments:

Contract price—settlement price X flat rate X volume (cargo size)

FFA settlement prices

Almost all FFA tanker contracts are settled on prices for 20 different routes, as published on a daily basis by the Baltic Exchange in London. The Baltic Exchange constantly reviews the popularity of physical trading routes worldwide (based on where there is strong demand for oil cargoes and strong supply—therefore buoyant trading volumes) and reflects this by publishing the relevant assessments.

These prices are formed on the basis of freight rate assessments as submitted to the Baltic by 18 shipbrokering companies worldwide. Settlement periods are generally on the basis of a month, quarter, or calendar year, although trading the balance of a month or closing out of an open position before the end of a settlement period can reduce this timeframe.

LIFFE=London International Financial Futures & Options Exchange (now called Euronext liffe).

BIFFEX=Baltic International Freight Futures Exchange (no longer in operation).