New Caspian oil production will bypass Russian transport

Most of the Caspian region’s new oil production will be transported to international markets via pipelines in Azerbaijan and Georgia, reducing Russia’s share of the regional oil transport market.

Caspian region oil production will increase from 80.4 million tons in 2005 to between 135 and 205.3 million tons in 2015.

Increases in output from Tengiz field in Kazakhstan, Kashagan field in the northern Caspian Sea just off the coast of Kazakhstan, and ACG field in the southern Caspian Sea just off the coast of Azerbaijan will key this rise in production.

Limited expansion potential on the Russian-operated Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) line and a desire by the region’s shippers to avoid additional use of Russian lines, will lead most of this new production to be carried by the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline instead.

Azerbaijan and Georgia’s share of the transportation market for Caspian oil will increase to 55% in 2015 from 22% in 2005, while the transportation market share of systems in Russia will decline to as little as 34% in 2015 from 66% in 2005 (Table 1).

Background

Russian Transneft aspires to maximize oil flows through its territory and take full control of the region’s transport systems. The Caspian nations do not support these aspirations.

Russian capacity is fully used. Russia’s major oil pipeline in the Caspian region also ends at the Black Sea, requiring ships to transit the heavily trafficked Bosporus and Dardanelles straights. Despite these limitations Russia strongly opposed development of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline and continues to oppose its expansion.

Two key factors will determine the competitiveness of any Caspian region oil transportation corridor:

The World Bank predicts increases in oil transportation capacity through Azerbaijan and Georgia to parallel growth in Caspian oil exports between 2005 and 2015, establishing secure transportation corridors outside of Russia.

This article will examine factors guiding the path oil follows out of the region and detail Caspian transportation infrastructure, including pipelines, ships, seaports, and terminals.

Change drivers

Existing oil transportation systems in the Caspian region do not have sufficient capacity to satisfy future demand for Caspian oil. Exports of Caspian oil will increase to 152 million tons by 2010 (from 80 million tons in 2005) and will reach as much as 205.3 million tons by 2015, requiring expansion of the region’s transport systems.

Transportation choices will depend in part on the capacity of the region’s two major pipelines, Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) and Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC).

Full use of the BTC’s already large capacity and expansion of the CPC can satisfy most of the expected demand for oil transportation through 2015. Failure to expand CPC’s capacity, however, will require development of other transport systems, including pipelines, rail systems, and location swaps.

CPC’s capacity limitations increase the likelihood that at least part of new Kazakh production from Tengiz field will travel through the BTC pipeline instead. But gas price disputes between Azerbaijan and Russia and similar incidents involving other countries have accelerated Azerbaijan’s efforts to develop alternative routes.

Kazakhstan reached agreement in principle in 2007 to export Tengiz oil by tanker to Baku and then through the BTC pipeline. Kazakhstan also signed a memorandum of understanding in 2007 creating the Kazakhstan Caspian Transport System (KCTS). KCTS would transport around 50 million tons of Kashagan crude oil once the field is developed, probably some time after 2010.

KCTS consists of a pipeline from Atyrau, where Kashagan crude comes ashore and is processed, to the new port of Kuryk, located just south of Aqtau and designed to handle tankers up to 60,000 dwt. From Kuryk the crude oil will move by tanker to Baku. From Baku most of the crude will flow into BTC for delivery to Ceyhan, Turkey. Small amounts might also move by rail to Georgian ports or through the Baku-Supsa or Baku-Novorossiysk pipelines.

The final development and ownership of the three Georgian ports on the Black Sea and the capacity and structure of the other transport links in Georgia and Azerbaijan will also affect the level and pattern of rail traffic through the Caucasus. KazMunaiGaz (KMG) owns Batumi Port and intends to reopen its oil refinery. SOCAR plans to begin operating a new port at Kulevi and wants to develop railway infrastructure.

Flow changes

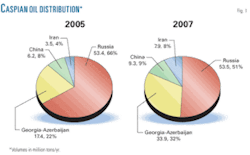

The routes for transporting oil from the Caspian comprise a complex network of pipelines, ports, ships, and railways. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of oil transportation by corridor in 2005 and 2007.

About two-thirds of total oil exports from the Caspian transited through Russia in 2005, with nearly a quarter traveling through Georgia and Azerbaijan and the remainder moving to Iran via swap, or to China. About 71% moved by pipeline and 25% by rail. The remainder (Iran swaps) was transported by tanker and rail.

Roughly one half of the Caspian region’s export oil moved through Russia in 2007 and one-third through Azerbaijan and Georgia. Rail’s share shrank to 17% from 25%.

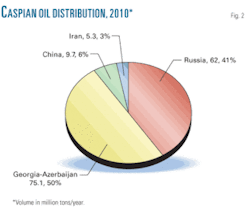

The total volume of oil exported from the region in 2010 will increase by as much as 50 million tons/year; or 40-50%. About 70% of this growth will come from the ACG field in the southern Caspian Sea and most of the remainder from Kazakhstan’s Tengiz field.

Failure to increase the capacity of the already-full CPC pipeline by 2010 will force incremental Tengiz production to find alternative routes. BTC will transport much of the additional crude oil, reducing Russia’s share of Caspian transport volumes to 41%, with the Caucasus share increasing to half (Fig. 2).

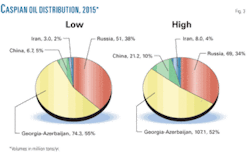

The low forecast for 2015 assumes a reduction in oil production from oil fields in Azerbaijan offset by growth of production in Kazakhstan’s Kashagan field, with little change occurring in the overall transportation pattern. BTC volumes would remain stable at about 60 million tons/year. Instead of Azeri crude representing 90% of BTC’s volume, however, about half of its volume would come from Kazakhstan, causing Russia’s share of exports to slip slightly to 38% (Fig. 3).

The high forecast poses a greater test for the transport network. An additional 45 million tons/year from Kazakhstan and 17 million tons/year from Azerbaijan will use all available capacity on both BTC and CPC. Some additional capacity is available in the Transneft system and on minor rail routes through Russia and the Caucasus, but such a large increase will require a major new pipeline.

This scenario diverts even greater volumes from Russia, with barely a third of regional exports crossing the country while half move through the Caucasus and 10% to China (Fig. 3).

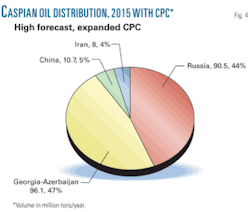

Expanding the CPC will reduce strain on the transport network under the high forecast. The extra CPC capacity would move north Caspian production, reducing pressure on the other routes and making future expansion of the Kazakhstan-China pipeline unnecessary (Fig. 4).

Current routes

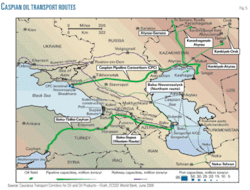

Caspian oil and oil products exports follow four main routes (Fig. 5, Table 2):

- North and west through the Russian pipeline and rail network, including the CPC pipeline. Volume on this route equaled 66 % of the Caspian region’s total exports in 2005.

- West through Azerbaijan and Georgian Black Sea ports. Volume on this route equaled 22% of the Caspian region’s total exports in 2005.

- South through Iran. Volume on this route equaled 4% of the region’s total exports in 2005.

- East to China by rail. Volume on this route equaled 8% of the region’s total exports in 2005.

Northern pipelines

Three pipelines operate from the northern Caspian Region:

- Atyrau-Samara.

- Kenkiyak-Orsk.

- CPC.

Most of Kazakhstan’s oil exports enter Russia through Transneft’s 20 million ton/year Atyrau-Samara pipeline. Kazakhstan’s exports via this route are limited by Kazakhstan’s annual oil export quota through the Russian pipeline system. Although no longer Kazakhstan’s main export route, Transneft, under an inter-governmental agreement, has been guaranteed 17.5 million tons/year of Kazakh oil for the next 15 years.

A second group of export pipelines includes the Kenkiyak-Orsk line, carrying oil from Aktyubinsk fields to the Orsk refinery in Russia and the Karachaganak-Orenburg pipeline, carrying condensate to Orenburg. The pipeline group moves 6.5 million tons/year. It acts as part of an oil swap arrangement supplying Kazakh oil to the Orsk refinery in Russia, while Russian oil transits the Omsk-Pavlodar pipeline in eastern Kazakhstan for use in Kazakhstan’s Pavlodar refinery.

The 1,580-km CPC links Kazakh oil fields to a Russian Black Sea terminal north of Novorossiysk. CPC operates outside the immediate control of Transneft. CPC’s initial capacity measured a nominal 28 million tons/year. Two independently constructed feeder pipelines from Kenkiyak and Karachaganak increased throughput in 2005 to 31 million tons/year. Throughput has increased since to around 35 million tons/year in 2007.

CPC’s owners hope to increase the pipeline’s capacity to 65 million tons/year by 2012, but expansion of the pipeline is proving difficult. Russia is trying to assert control over the CPC pipeline through various licensing efforts and is keen to increase its tariff to at least $30.73/ton from the current $28.25/ton. Russia has also taken steps to transfer its shares in CPC to Transneft, CPC’s direct competitor.

Other factors working against expansion of the CPC pipeline include its estimated $3.5 billion cost. BP seeks to sell its 6.6% share in the CPC pipeline at least in part due to the costs. Oman sold its 7% share to Russia in 2008.

Kazakhstan, the prime supplier of oil transported through the CPC pipeline, is also increasingly wary of having its oil transported through a pipeline potentially controlled by a Russian monopoly and is trying to make it possible to export via the BTC pipeline instead.

If capacity of the CPC pipeline is not increased, transportation of Caspian oil to world markets will use a combination of alternative pipeline routes and other resources already in-place or under development.

Oil companies in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan are already developing such alternatives. KazMunaiGaz has invested $200 million to purchase Georgia’s Batumi oil terminal, while Azerbaijan has built a new Black Sea port in Georgia at Kulevi. Besides moving additional future volumes, these facilities will help if geopolitical problems prevent movement of oil through Iran or Turkey.

Georgia’s Black Sea ports Batumi, Kulevi, and Supsa also have sufficient transshipment capacity to handle increased oil flows. Kulevi’s original 4-5 million ton/year capacity increased to 10 million tons/year in 2008. Plans exist for further expansion of Kulevi to 20 million tons/year and Batumi to 25 million tons/year from 15 million/tons year.

Southern pipelines

Three pipelines operate from the Caspian’s western shore:

- Baku–Novorossiysk.

- Baku-Supsa.

- BTC.

The Baku–Novorossiysk pipeline carries 6 million tons/year 1,400 km and could be expanded to around 15 million tons/year by adding pumping stations at a cost of about $300 million. The pipeline’s tariffs are competitive, but its small capacity will limit its viability as an export route.

The Baku-Supsa pipeline, known as the Western route, entered service in 1998 using refurbished sections of a partially constructed product pipeline in Azerbaijan and connecting it to an unused crude oil pipeline running from northwest of Tbilisi to Batumi. A subsequent branch of the pipeline connected it to the port of Supsa, where an offshore loading facility was constructed. The 530-mm OD pipeline has a capacity of 7 million tons/year. Additional pumping stations can increase its capacity to about 10 million tons/year at an estimated cost of $100 million.

The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline crosses Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. The pipeline starts near Baku at the Sangachal terminal, which receives oil from Azeri, Chirag, and Gunashli (ACG) offshore oilfields in the Caspian Sea. The pipeline ends at a marine terminal on the Mediterranean Sea in the Turkish port of Ceyhan, where crude tankers are loaded. BTC construction sought to create a route not under Russian control.

BTC cost an estimated $3.7 billion. BP holds a 30% stake in the BTC Co. consortium running the pipeline. Other consortium members include Azerbaijan’s state oil company SOCAR (25%), Amerada Hess (2.36%), ConocoPhillips (2.5%), Eni (5%), Inpex (2.5%), Itochu (3.4%), Statoil (8.71%), TotalFinaElf (5%), TPAO (6.53%), and Unocal (8.9%).

BTC can move 1 million b/d (50 million tons/year) across 1,780 km. Additional pump stations could increase capacity to 60-65 million tons/year. The pipeline’s OD through Azerbaijan measures 1,070 mm, increasing to 1,170 mm as it rises from the plains into the Caucasus Mountains and Georgia. The pipeline reverts to 1,070 mm for the portion across Turkish Anatolia and shrinks to 865 mm as it nears Ceyhan.

Kazakhstan-China pipeline

The 962-km eastern section of the Kazakhstan-China Pipeline provides the first direct link between oilfields in central Kazakhstan and the Chinese market. The pipeline links Kazakhstan’s South Turgay basin and the Russian pipeline system to refineries in western China. Deliveries to Dushanzi refinery began in July 2006. Initial capacity (and throughput) of the line measures 10 million tons/year, with oil coming from both Kazakhstan and Russia.

Beyond transporting oil from Kumkol fields in South Turgay (now majority owned by China National Petroleum Corp.), the pipeline transports Kazakh oil delivered to the pipeline by rail from other oil fields being developed by CNPC in Aktobe, in the northwest part of the country.

Black Sea

A Mar. 15, 2007, memorandum of understanding between Bulgaria, Greece, and Russia set up the framework for construction of a Burgas-Alexandropolis pipeline, a Russia-controlled pipeline between the Bulgarian Black Sea port of Burgas and the Greek port of Alexandropolis. Such a pipeline could facilitate transport of Caspian oil to world markets via the Black Sea without passing through the crowded Bosporus and Dardanelles straits.

The pipeline would transport 35-50 million tons/year as an extension of the CPC route connecting Kazakh oil fields to a Russian Black Sea terminal north of Novorossiysk. The MoU had construction beginning in October 2009 with the pipeline entering service in 2011. To date, however, neither a strategic impact assessment nor an environmental impact assessment has been completed.

The pipeline is also not yet funded. The two most likely sources of financing for the project are the Interstate Oil and Gas Transport to Europe (INOGATE) program and the European Investment Bank. Other economic concerns include limited financial benefits to transit countries and possible damage to tourist revenues.

Bulgaria would receive an estimated $35-50 million/year in transit fees. Additional tax revenues for both Bulgaria and Greece would be limited. At the same time, the Burgas region is the main tourist area on the Black Sea coast of Bulgaria. Construction and operation of the pipeline could threaten tourism, not just by the direct environmental damage of possible oil spills, but also by reducing the area’s visual appeal.

The question of who will bear the cost of recovering from pipeline accidents also still requires clarification. The memorandum of understanding did not provide guidance on this issue. Russia holds 51% of the company and Bulgaria is considering selling its minority share to foreign companies, further complicating progress on the pipeline.

Caspian shipping

The break-up of the former Soviet Union assigned the Caspian Sea fleet to the country of its home port. The Caspian Shipping Co. (CASPAR) registered its ships in Baku, assigning these ships to Azerbaijan and leaving Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan without a fleet. CASPAR remains the largest shipping company in the region.

The CASPAR fleet has an average age of more than 20 years. Many of the vessels are in poor condition. CASPAR has contracted Meridian Shipping, owned by Middle East Petroleum (MEP), to operate the fleet. CASPAR until recently handled around 90% of all cross-Caspian oil shipments, resulting in such comparatively high freight rates as: Aqtau–Makhachkala, $7-9/ton; Aqtau–Baku, $7-8/ton; and Aqtau–Neka, $12-12.5/ton.

The arrival of three Russian-affiliated shipping companies serving non-Azeri ports has increased competition in the Caspian market.

- Palmali is a Turkish company operating a total of about 100,000 dwt of modern tankers under the Russian flag with the support of Lukoil.

- Volgotanker operates 10 tankers totalling 50,000 dwt in the Caspian in winter, transferring most of them to the Russian river trade during the summer. The ships are small and more than 20 years old, but the company is unlikely to replace them with larger vessels designed for the Caspian since its core business lies in the Russian river trade.

- Safinet NJ is the shipping subsidiary of Makhachkala port. It operates five 6,000-dwt tankers on bareboat charter between Makhachkala and Aqtau.

Aqtau is Kazakhstan’s principal seaport, located on the Caspian Sea in southwestern Kazakhstan. Aqtau International Sea Commercial Port owns the facility. Aqtau has five oil berths (with a sixth under construction), three general cargo berths, a grain terminal, a rail ferry berth accessible to oil tankers, and a small basin for port craft and other small boats. KazMorTransFlot has leased the five oil berths for 49 years. Aqtau’s end-2005 oil terminal capacity measured 13.5 million tons/year: 10-11 million oil and 2.5 million products.

The approach channels and oil berths have 6-m drafts, limiting tankers to 12,000 dwt. The port handled 10.7 million tons of oil in 2007.

Turkmenistan has oil terminals at Okarem and Adjala and a major port at Turkmenbashi. State Turkmen Maritime and River Lines, which has ministry status, owns the facilities. Turkmen terminals handled about 4.1 million tons of oil and oil products in 2007, but plan to expand.

Iran has several sea ports, but only Neka handles oil. Pipelines transport oil from Neka to refineries near Tehran. Iran makes an equivalent amount of its own oil available at the Persian Gulf in exchange for the Caspian imports. Iran has upgraded Neka and its domestic pipelines to increase route capacity to 7.5 million tons/year. This route offers basis advantages over Black Sea routes for marketing Caspian oil to East and South Asia. Caspian crude shipments to Neka have tripled in the past 2 years.

Azerbaijan has one major port, Baku, and four oil terminals—Baku, Sangachal, Dubendi, and Garadagh— the last of which is still under construction. The state owns Baku International Sea Port. It has a general terminal in the center of the city, and two rail-connected oil terminals. The port has rail-ferry links with Turkmenbashi and Aqtau, but does not have pipeline access.

State SOCAR owns the 10-million ton/year Dubendi oil terminal, located 40 km northeast of Baku. The terminal has rail and pipeline connections. The rail loading facility can simultaneously load 78 rail tank wagons with crude and 32 with product.

Dubendi also has a connection to the Northern pipeline. This connection has not been used for many years and would require rehabilitation before it could be used again. A new pipeline to the AIOC terminal at Sangachal, considered for several years, will likely be constructed if the Dubendi terminal is expanded to receive Kazakh oil.

The Sangachal area has two terminals 12 km apart and connected by two pipelines, one flowing each direction. Sangachal port lies 45 km south of Baku. It has two moorings for 10,000-12,000 dwt tankers. The terminal can transship 13 million tons/year and has 172,000 tons of storage. Owner AzerTrans is building four more 17,200-ton tanks. This terminal, operated by MEP, also has a rail loading facility.

A separate Sangachal onshore terminal receives oil by pipeline from the offshore ACG field for shipment through connections to the BTC, Northern, and Western pipelines. AIOC owns this terminal.

Ocean Energy, in association with MEP, is building a new oil terminal at Garadagh, 40 km south of Baku. Completion of this project will lead to closure of the Baku terminals. The new terminal, designed for trans-Caspian shipping of new Kazakh production, will handle 60,000 dwt tankers and have a capacity of 10-20 million tons/year.

Bibliography

Aqtau Port Development, Master Planning & Feasibility Study, Traffic Forecasts, October 2007.

BP Statistical Review of World Energy, British Petroleum, June 2007.

Caucasus Transport Corridor for Oil and Oil Products - Draft, prepared by ECSSD World Bank, June 2008.

Georgian Railway Capacity Building in Freight Marketing, Report One, World Bank, prepared by Corporate Solutions, February 2007.

Georgian Railways Limited - Oil Transit -Assistance with Project Preparation, Draft Interim Report, EBRD, September 2004.

Kazakhstan Transport Sector Strategy: Policy Note on Ports, Shipping and Inland Water, World Bank, September 2005.

World Energy Outlook 2006, International Energy Agency (IEA), OECD/IEA, 2006.

The authors

Paata Tsagareishvili ([email protected]) is deputy head of the transport department at Georgia’s Ministry of Economic Development. He has worked for the Georgian government since 1996. He holds a PhD in railway building (2004) from Georgian Technical University and is a member of the Georgian Marketing Association.

Gogita Gvenetadze ([email protected]) is chief specialist in transport department at Georgia’s Ministry of Economic Development. He previously worked as specialist in the marketing service of the Georgian Railway. He holds an MA (2005) in social, economic, and political geography from Iv. Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University and is a member of the Georgian Marketing Association.