Another 9 bcfd of US LNG export capacity required by 2035

Jeremy Goh

Kent Bayazitoglu

Ajey Chandra

Baker & O’Brien Inc.

Houston

Increased natural gas demand from European countries keen to avoid imports from Russia has boosted US LNG export prospects. This improved export outlook has been met by three final investment decisions (FID) in the past year. However, recent forecasts indicate the need for several more plants to be completed by 2030. Baker & O’Brien expects that another 9 bcfd of capacity may be required by 2035.

Meeting demand for these additional volumes will be difficult. US LNG projects face increased headwinds in reaching FID, such as tighter credit, stricter regulatory processes, and limited pipeline connectivity. US LNG exports, however, will likely continue to grow into the next decade as more plants are added despite development plans for Mexican LNG terminals that will be competing for the same gas supply.

Background

In 2022, the US exported 3.85 tcf of natural gas, equivalent to 10.6 bcfd or about 80 million tonnes/year (tpy). These volumes put the US ahead of Qatar and just behind Australia among the world’s largest LNG exporters.

Europe emerged as the top destination for US LNG in 2022, dethroning East Asia, the top destination for the previous 2 years. The change in regional destinations was a direct response to the reduction in Russian natural gas pipeline flows to Europe following the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

In fact, Europe held the top four destination countries for US LNG in 2022, as France, the UK, Spain, and the Netherlands collectively imported about 5 bcfd (38 million tpy). Fig. 1 shows the regional destinations of US LNG cargoes from 2016 through March 2023.

European demand

European LNG demand more than doubled in 2022, from 3.3 bcfd to 7.3 bcfd. This trend looks to continue through 2023 as European gas demand will require more non-

Baker & O’Brien expects nine new LNG import terminals, with a combined capacity of 3.8-4.4 bcfd, to be placed in service end-2023. Four of these will be in Germany, given its previous role of receiving and transporting much of the Russian pipeline gas to final consumers in Northwestern Europe. The accompanying table shows the terminals which have or will enter service in 2023 and their expected capacity.

US export capacity

Beyond 2023, Baker & O’Brien expects an additional 7.3 bcfd of US capacity to come online, including QatarEnergy and ExxonMobil Corp.’s 15.6-million tpy Golden Pass LNG plant and Venture Global’s 20-millon tpy Plaquemines LNG plant.

In March 2023, Sempra Infrastructure announced FID on the 12-million tpy first phase of its $13-billion Port Arthur LNG project. Phase 1 will use two trains and enter service 2027-28.

When post-FID projects (including those under construction) reach commercial operation, US LNG export capacity will increase to 18.7 bcfd (142 million tpy) by 2028.

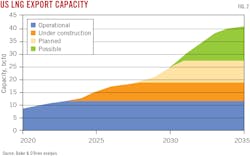

Beyond these expected plants, at least ten additional US LNG export projects are at various stages of planning. Adding all these projects brings the potential US export total to around 40 bcfd (Fig. 3), or roughly a third of US gas production in 2022 and more than half of global LNG liquefaction capacity that year.

EIA predicts flat domestic gas consumption, as demand from the power industry, a big growth engine over the past 20 years, flattens out. But even with this, increased exports, primarily LNG, are projected to drive gas production from 100 bcf/d in 2022 to 108 bcf/d in 2035. Modest growth in pipeline exports to Mexico is expected, but this figure may be revised higher if more Mexico-based LNG plants are constructed.

Most US gas production growth is expected to come from shale gas and associated gas from oil production, which is prolific in the Permian basin. Permian basin drilling choices are almost entirely driven by oil prices. EIA recognizes this by publishing a high gas-production case for high oil prices and a low gas-production case for low oil prices. If oil prices decline and stay low during the forecasted timeframe, producers will drill fewer wells meaning less associated gas. If oil prices increase and remains high, producers will drill more oil wells which means more associated gas.

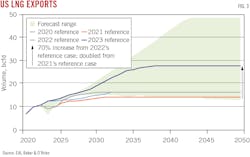

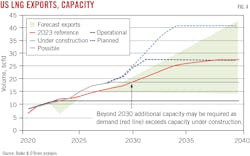

The EIA’s outlook for LNG exports represents a 70% increase from the 2022 reference case and a doubling since the 2021 reference case. As Fig. 4 demonstrates, the higher export forecasts are coupled with more uncertainty.

This demand growth from Europe benefits US-sourced LNG over other potential LNG sources, as the shipping distance from the US Gulf Coast (USGC) to Europe is shorter than most other sources. It also avoids canal passages.

Baker & O’Brien cautions against an over-reliance on the exact volume projections, as US LNG exports are uniquely flexible from a destination standpoint. US LNG cargoes are not bound by firm volume commitments or restrictive destination clauses often found in LNG contracts from other supply sources. For instance, if Asian or European gas prices decline, and US prices rise, US liquefaction is likely to be curtailed. This scenario occurred in 2020 when the price of gas collapsed globally due to COVID-19 pandemic responses.

The flexibility of US LNG is most desirable for buyers uncertain about their long-term gas demand. Traditional LNG buyers, such as Japan, face unprecedented uncertainty with their long-term energy mix due to the influence of low-carbon targets and renewable goals. There are many unknowns regarding how or if these targets can be met, so replacing expiring LNG import contracts is very complicated. Traditional LNG supply contracts have strict (minimum) volume requirements, defined destination ports, and no resell clauses. US LNG’s flexibility is useful in managing contract risk as surplus volumes can always be traded on the open market or not taken if the contract provides that flexibility.

Much of 2023’s outlook growth is also predicated on the assumption that Russian gas exports to Europe will remain restricted. If political conditions change, Russian gas exports to Europe could resume. However, imports from Russia will likely remain below previous projections, even in this unlikely scenario, as European nations reassess their energy security needs. The sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines from Russia to Germany further buries the likelihood of Russia returning as a major gas supplier to Europe.

Growth projections

Examining the forecasts for additional exports beyond 2030, the necessity for additional liquefaction capacity becomes clear. Fig. 4 combines the EIA’s AEO reference case and range of forecasts with forecast capacity additions.

The AEO assumes that short-term exports are capacity constrained until about 2025. Beyond that, the capacity additions from plants under construction, or the “second wave,” should be able to handle projected export volumes to 2030.

Further demand growth will depend on new projects—the “third wave”—reaching FID and completion by 2030. If the AEO’s most extreme high-and-fast case materializes, other plants beyond those in development will be needed to meet demand by 2035.

In other words, sufficient capacity exists or is under construction to meet the EIA’s LNG export forecasts, but only until 2030.

US LNG FIDs

Reaching FID for a US LNG export project requires meeting several criteria:

- Sales, capacity agreements. A long-term (ideally 20-plus years) capacity or sales commitment is necessary to ensure project revenues. The capacity or sales agreement must be firm for most of the anticipated volumes, even if the buyer isn’t required to take the volume. The buyer must also be creditworthy.

- Financing. Whether the project is to be paid for by equity, debt, private equity financing, or a combination of these, the equity holders or bankers need to be reasonably confident that their loans can be repaid. As such, financiers closely examine the sales agreements, the buyers’ creditworthiness, the plant owner’s reliability as an operator, and the balance sheet of the project backers.

- Regulatory approvals. A range of approvals from regulatory bodies such as the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and Department of Energy (DOE) are required before FID can be made. These approvals are mostly focused on environmental impacts, but may also consider impacts related to other issues. A notable amount of engineering is required to achieve regulatory approvals, which takes time and is expensive.

- Gas supply. Projects must have an adequate and secure gas supply. Often, the biggest problem is securing transportation from supply basins to the project site. Pipeline projects themselves face a wide range of regulatory hurdles and financial risks. There are growing difficulties in all these criteria for new LNG projects.

Much like Japanese utilities, European utilities prefer shorter-term capacity commitments because of uncertainties in the speed and depth of domestic energy transitions. Europe is keen to procure alternatives to Russian gas. However, Europe’s energy transition away from carbon fuels may be at odds with securing long-term deals to buy LNG. European utilities face increasing uncertainty regarding gas demand, as domestic heating veers away from gas and towards electricity and as renewables gain a larger share of the energy mix. These uncertainties mean that utilities may prefer shorter-term capacity commitments than the 20-year contracts that have traditionally underpinned new LNG projects.

Another problem is the current global credit contraction making financing harder to obtain. This credit contraction is evidenced by multiple surveys confirming a tightening of bank lending and bank lending standards. Banks are tightening credit supply primarily because they anticipate a global economic slowdown.

The credit contraction favors projects supported by strong balance sheets. During a credit contraction, banks will first pull back on risky lending. Loans to projects with a higher percentage of external debt are deemed riskier. As a result, projects without internal balance sheet financing or highly leveraged projects may struggle.

The DOE recently tightened its rules on export licenses by denying an extension to Energy Transfer’s 16.45-million tpy Lake Charles LNG project. Projects typically have 7 years to start exports from the moment they receive their DOE export licenses. This is designed to encourage stalled projects to expedite FID or lose export authorization.

The process of permitting additional interstate gas pipeline capacity, especially in the Northeast, has become extremely difficult, with several major new pipelines being cancelled due to environmental opposition. Growth in production from the Marcellus and Utica shales in the Appalachian region will be restricted by takeaway capacity. As a result, much of the gas supply for US LNG export projects will need to be from sources closer to the LNG plants or within state boundaries.

For Texas projects, this means more volumes from the Permian basin. Additional pipeline capacity coming online to take gas from the Permian includes Kinder Morgan Inc.’s Gulf Coast Express pipeline expansion (570 MMcfd) and Permian Highway pipeline expansion (550 MMcfd), WhiteWater Midstream LLC’s Whistler pipeline expansion (500 MMcfd), and the Matterhorn Express pipeline (2.5 bcfd), being developed by a consortium of Devon Energy Corp., EnLink Midstream Partners LP, Marathon Petroleum Co. LP, and WhiteWater. However, with 5 bcfd of LNG export capacity coming online in Texas alone by 2028, even more pipeline capacity will be needed.

In Louisiana, much of the additional gas supply for LNG export projects is expected to come from Haynesville shale in northwestern Louisiana. Some projects announced include DT Midstream Inc.’s Louisiana Energy Access expansion (900 MMcfd), Williams Cos.’ Louisiana Energy Gateway (1.8 bcfd), and M6 Midstream LLC’s New Generation Gas Gathering pipeline (1.7 bcfd).

Mexican LNG plants

Mexican export projects are an important factor in the US LNG supply-demand balance. There are two such projects currently under construction with several more progressing towards FID.

Energia Costa Azul Phase 1, owned by Sempra, took FID in 2020 and is under construction. It is on track to start operations in early 2025 with a capacity of 3.25 million tpy. Another two trains are planned, bringing Energia Costa Azul’s total capacity to about 15 million tpy.

Fast LNG Altamira, a floating LNG (FLNG) plant New Fortress Energy is building, is scheduled to start operations at the port of Altamira on the east coast of Mexico by August 2023. This 1.4-million tpy plant is planned to be the first of two FLNG at Altamira with another planned for the offshore Lakach field in 2024 (OGJ Online, Dec. 5, 2022).

Additionally, Mexico Pacific LNG has progressed its Saguaro LNG project, signing long-term sales and purchase agreements with ExxonMobil, Guangzhou Development Group, and Shell PLC. Phase 1, consisting of two trains totaling 9.4 million tpy, is expected to come online later in the decade.

Other planned Mexican export projects could bring the country’s total export capacity to more than 40 million tpy by 2035. Most of these projects aim to export primarily Permian-sourced gas; thus, they are competing with US-based projects for gas supply. Except for the Altamira projects, they are on the West Coast of Mexico and will target Asian customers while avoiding the Panama Canal. If US export projects are delayed or cancelled, the Mexican export routes could still provide takeaway capacity for Permian associated gas.

The authors

Jeremy Goh (jeremy.goh@bakerobrien) is a consultant at Baker & O’Brien helping clients with complex energy matters, especially in the gas and LNG industry. He has extensive international experience in gas and energy strategy and planning, and investment projects. He has an MS (1999) in engineering science from the University of Oxford and an MBA (2022) from Texas A&M University.

Kent Bayazitoglu is a senior consultant at Baker & O’Brien. He draws upon his 23 years in the energy industry to advise clients on energy commodity markets, transactions, disputes, and economic modeling. He has a BS (1998) in mechanical engineering from Rice University, Houston, and an MBA (2003) from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Ajey Chandra is an executive vice president at Baker & O’Brien and has 37 years of experience in the energy industry. Before joining Baker & O’Brien, he was CEO of consulting firm Muse, Stancil & Co. and prior to consulting he held leadership positions in natural gas and midstream operations in a variety of operating companies. He has a BS (1986) in chemical engineering from Texas A&M and an MBA (1991) from the University of Houston.