US debate on LNG exports centered at Energy Department

Steven Miles Thomas Eastment

Baker Botts LLP

Washington, DC

Use of hydraulic fracturing to produce natural gas and oil from shale and other tight formations has transformed US energy markets. Vast new oil and gas reserves are now commercially accessible, placing North American energy independence within reach.1

This shift in US energy supply has driven down domestic gas prices, breathed life into a broad array of long-struggling US industries, and replaced the need for LNG imports with a growing potential for substantial LNG exports.

The prospect of the US changing into a net exporter of natural gas has prompted an increasingly sharp debate over whether the US should send its newfound energy bounty abroad where current prices exceed US prices (Fig. 1). The US Congress is unlikely to stay on the sidelines on this policy issue, as evinced by the introduction of legislative proposals to authorize greater gas exports and the Feb. 12, 2013, hearings on LNG exports by the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources.

Unless and until current law is changed, however, the epicenter of the debate will be at the US Department of Energy (DOE). This article explains why that is the case and suggests steps by current and future applicants for enhancing their chances of winning approval for their proposed projects.

Export license authority

Section 3(a) of the Natural Gas Act (NGA), as amended, authorizes the import and export of natural gas, including LNG, to and from a foreign country, unless it would "not be consistent with the public interest." The provision creates a rebuttable presumption that a proposed export of natural gas is in the public interest, and DOE must grant such an application unless opponents overcome that presumption.2 The authority to grant licenses under this standard lies with the DOE's Office of Fossil Energy (DOE/FE).

The 1992 Energy Policy Act amended the NGA to require that applications to export to countries with which the US has a free trade agreement (FTA), requiring national treatment for trade in natural gas be "deemed to be consistent with the public interest" and "granted without modification or delay." The law thus removes DOE/FE's discretion over exports of natural gas to such countries.

Importantly, DOE/FE does not provide for public comment on FTA export applications. The average processing time between the filing of an LNG FTA export application and issuance of an order has been 65 days. With the exception of two pending applications, DOE/FE has approved all FTA export applications for proposed LNG export projects.

This automatic and expedited authorization process provides projects with considerable regulatory certainty with respect to DOE export authorizations to FTA countries. The size of the market encompassed by the 18 current FTA countries is limited, however: Among them, only South Korea, Singapore, Chile, and the Dominican Republic currently import LNG.3

For applications to export LNG to non-FTA countries, DOE/FE will undertake the required public-interest assessment under the NGA. It has interpreted its obligations under the NGA and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to require consideration of the following in evaluating applications for natural gas exports:

• The domestic need for the natural gas proposed to be exported.

• Whether the proposed exports threaten the security of domestic natural gas supplies.

• Whether the arrangement is consistent with DOE's policy of promoting competition in the marketplace by allowing commercial parties to negotiate freely their own trade arrangements.

• The environmental effects of the proposed decision.

• Any other issue determined to be appropriate.4

Shortly after approving the first application for a non-FTA LNG export authorization in mid-2011 for Sabine Pass Liquefaction, DOE delayed the issuance of more non-FTA authorizations, pending release of a two-part study commissioned by DOE/FE to determine how LNG exports might affect US supply and global markets.

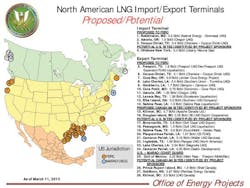

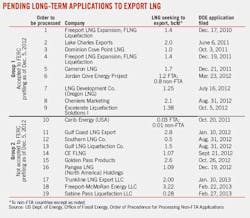

A backlog of 19 non-FTA applications, shown in the accompanying table, has since accrued during the hold. Fig. 2 shows the location of proposed or potential LNG export plants.

LNG export study

Part 1 of the LNG export study followed an August 2011 request by DOE/FE to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) to analyze the effect of exports of LNG on US natural gas demand. Issued in January 2012, EIA's report considered 16 scenarios under different assumptions on gas supply, demand, and exports.

EIA identified four general effects associated with LNG exports:

1. Increased gas exports would lead to increased US gas prices with the rate of the increase determined by how rapidly exports grew.

2. Of the natural gas exports, 60-70% would be supplied by increased gas production supplemented by a minor increase in Canadian imports.

3. The remainder of gas exports would be met by reduced US consumption because of higher prices.

4. Consumers would see an increase in natural gas and electricity costs, the amount of increase varying based on how rapidly gas exports grew.

On Dec. 5, 2012, DOE/FE released Part 2 of the study, a commissioned report developed by NERA Economic Consulting on the macroeconomic impact on the US economy of LNG exports.

The NERA study used the same scenarios as in the EIA report. Most notably, NERA observed that the EIA report determined the relationship between exports and "domestic prices without, for example, considering whether or not those quantities of exports could be sold at high enough world prices to support the calculated domestic prices."5 NERA concluded that the global gas market would not accept the full volume of exports if the export prices were as high as projected in the EIA scenarios.

NERA also concluded:

• In all scenarios, the US would experience net economic benefits from exporting natural gas directly proportional to the volume of LNG exported, with the greatest benefits occurring with unrestrained exports.

• US natural gas prices would increase but not as greatly as predicted by EIA because competing global supplies will replace US exports above a certain price.

• The export of LNG will shift income from labor and investment income to resource income and will result in net transfers that will reduce the US trade deficit.

• Serious competitive impacts are likely to be confined to narrow segments of industry that are sensitive to natural gas prices but in no scenario are energy-intensive industries as a whole projected to have a loss in employment or output greater than 1% in any year.

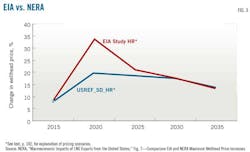

Fig. 3 compares EIA's study and NERA's projected US natural gas prices. The assumed EIA price scenario used in Fig. 3 contemplates high US LNG exports of 12 bcfd with capacity rapidly being phased in at 3 bcfd/year: the EIA's "High export/Rapid growth" scenario, or "EIA study HR."

The scenario used by the NERA study and shown in Fig. 3 is based upon:

• The US Reference Case from EIA's Annual Energy Outlook 2011.

• A supply-demand shock that presumes increased worldwide demand caused by shutdowns of some nuclear capacity and assumes that key LNG exporting regions will not increase their exports above current levels despite the demand shock.

• The same High export/Rapid growth assumptions used in the EIA study. Hence, in Fig. 3: "USREF_SD_HR" refers to the EIA's reference case, supplemented by a potential supply-demand (SD) shock, under a scenario of high export and rapid growth (HR) of capacity.

DOE/FE incorporated the LNG export study as part of the administrative record for each of the then pending non-FTA application proceedings.6 It also invited public comment on both reports to be entered into the administrative record in each of these proceedings.7

DOE/FE advised that the findings and conclusions of the EIA and NERA studies have not been adopted by DOE/FE but that they will be considered, along with all other information in the record in each proceeding, to determine if an application for a license to export to a non-FTA country satisfies NGA's public interest standard.

After releasing the LNG export study, DOE/FE divided the pending applications into two groups (table), expecting to review first the filings of applicants for export into non-FTA countries that began the prefiling process at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) as of Dec. 5, 2012.

DOE develops a record

The initial period for comment on the LNG export study ended on Jan. 27, 2013. Reply comments were due Feb. 25. By mid-February, DOE reported it received in the first round alone more than 100,000 comments from individuals, companies, trade associations, environmental groups, members of Congress, and others, although many submissions were letters filed by members of the public as "part of an initiative sponsored by a public interest organization."8

As DOE has made clear, the LNG export study is not the final word on whether and to what extent exports will be authorized to non-FTA countries. Accordingly, both opponents and supporters took the opportunity to submit substantial data and other material in their comments.

For example, the Sierra Club submitted comments in opposition, focusing on its views that hydraulic fracturing is harmful to the environment and that exporting LNG will exacerbate climate change because of the energy expended in liquefying and transporting natural gas.

Some large companies engaged in energy-intensive, trade-exposed (EITE) industries formed America's Energy Advantage, a coalition to oppose LNG exports. Their comments argued exports could drive up domestic gas prices, making their products less competitive in both US and international markets.

Supporters of exports, including the export license applicants themselves, submitted extensive comments generally lauding the NERA study and its conclusions. They also provided updated projected gas production data to supplement NERA's study to show that any projected increases in domestic gas demand beyond that stated in the NERA study were more than offset by additional increases in supply.

Other commenters advised that restrictions on the export of LNG could violate free-trade principles enforced by the World Trade Organization, in which the US is active, and would encourage other countries to employ similar restrictions on their exports.

Congressional role

The US Congress can change the governing standards for export approvals either to rein in or to broaden DOE's discretion to authorize a license to export gas to non-FTA countries, and members of the current Congress have already initiated legislation. For example, a bill proposed by Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.) would treat Japan and member countries of the North Atlantic Treating Organization as FTA countries, effectively eliminating DOE's discretion to deny exports to those countries.

Further, the proposed legislation would give the US Secretary of State, in consultation with the Secretary of Defense, authority to add countries to those automatically eligible if they find it would be in the national security interest of the US.9

Those favoring expansion of the list of countries to which exports must be approved, however, will likely sail into strong headwinds. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, and US Rep. Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.), of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, have already voiced concerns about unfettered LNG exports, echoing the arguments of the Sierra Club and other opponents.

More recently, Sen. Wyden suggested that Congress should encourage DOE to find the "sweet spot" that allows LNG exports only to the extent needed to encourage production while maintaining relatively low gas prices for industrial consumers.10

Future

DOE/FE has established the order in which it will process the pending non-FTA LNG export applications (see table) but has provided little indication of how the LNG export study will affect its disposition of these applications. DOE/FE previously stated that it intends to review the applications on a case-by-case basis11 and that it will evaluate the cumulative impact of each authorization to determine if the authorization could pose a threat to the public interest.12

This suggests there will be a material advantage to those projects higher in the processing queue. Because a cumulative review could effectively raise the public-interest standard that must be met by each subsequent application, applications further down the list not only will take longer to be considered, but they will also face greater scrutiny.

It is not clear, however, what DOE's cumulative impact review will entail. For example, projects in the Northwest US will have minimal, if any, effect on Henry Hub pricing and on prices paid by residential and industrial customers east of the Rocky Mountains.

Moreover, to the extent that these projects draw their gas from Canada, there should not be the same security-of-supply and environmental impact considerations as there are with US-sourced supply. Will these regional differences matter for DOE's consideration of cumulative impacts?

Environmental impacts also are a public-interest factor and have become the focus of some export opponents. Sierra Club has strongly advocated that FERC and DOE consider the link between LNG export terminals and LNG export authorizations and the increase in natural gas production through hydraulic fracturing. Thus far, Sierra Club's argument has not gained traction with either FERC or DOE.

The NGA designates FERC as lead agency for purposes of complying with NEPA for LNG export projects,13 making FERC responsible for the preparation of an environmental impact statement for each project. Sierra Club filed a late intervention with DOE in the Sabine Pass Liquefaction proceeding requesting that DOE supplement FERC's environmental determination on Sabine Pass to consider cumulative environmental impacts from shale gas production.

DOE rejected the request, accepting FERC's determination "that induced shale gas production is not a reasonably foreseeable effect for purposes of NEPA analysis."14 The US Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed a similar determination by FERC in the context of a new pipeline project, finding that FERC reasonably concluded the impacts of shale developments were insufficiently causally related to the project.15

In contrast, at least one regional office of the Environmental Protection Agency has requested that FERC expand the scope of its environmental review for LNG export plants to include indirect effects related to gas drilling and combustion of natural gas.16

In grappling with information provided to it, DOE must weigh multiple environmental, economic, and other factors relevant to determining the public interest. These same factors form the contours of the looming policy debate in Congress in addressing what changes, if any, it should impose on DOE through new legislation.

Applicants' steps

With so many factors being evaluated by the executive branch, Congress, and ultimately the courts, what steps can applicants take to improve the likelihood of their application being granted and their export project proceeding?

1. The breadth and complexity of DOE's inquiry underscores the need for an applicant to put forward a comprehensive and well-supported case.

Whatever DOE may decide in response to the LNG export study and processing applications, its decision almost certainly will be challenged in federal court. The decision will be reviewed by the courts under the standards of the Administrative Procedure Act. The law gives substantial deference to the DOE decision, and the court will uphold the agency's decision unless it finds that the decision is not supported by substantial evidence in the record, is arbitrary and capricious, lacks a rational basis, or is contrary to statutory requirements.

These standards of review make it critically important for applicants and supporters of exports to ensure that the record before the DOE contains a thorough analysis of the key issues raised by opponents and a fully developed evidentiary basis for the analysis.

Such a record will provide a basis on which the DOE can support and successfully defend on appeal a decision to authorize exports to non-FTA countries. Conversely, such a record can form the basis of challenging in court a decision by DOE to deny export applications.

2. If an applicant for a non-FTA DOE export authorization has not already done so (and almost half have not), it should promptly begin the FERC prefiling process.

Initiating the prefiling process involves submitting a filing with the US Coast Guard regarding proposed LNG tanker transits, meeting with FERC staff, soliciting third-party environmental contractors to assist FERC in its environmental review, and submitting to FERC the project description and details required by its regulations.

Upon obtaining such prefiling approval from FERC, the applicant should commit to pursuing its application diligently and expeditiously. In establishing the order in which it will process non-FTA LNG export applications, DOE said it would first look at those applications that had received FERC approval to begin the FERC prefiling process as of Dec. 5, 2012 (Group 1 in the table), in the "general order" in which the DOE received them.17 All other applications (Group 2) will be processed in the order in which they were received at DOE.

While an applicant may have missed the Dec. 5, 2012, cutoff to begin prefiling with FERC, DOE's order appears to reflect a policy of giving priority to applicants that have demonstrated their commitment to an LNG export project by investing the resources to begin the FERC approval process. DOE may view more favorably applications in the second group for which applicants have proposed a concrete project to FERC.

3. Sign a long-term agreement with one or more creditworthy customers.

Since one of the criteria considered by DOE/FE in its public-interest review focuses on the marketplace, evidence of market support for a project (even though contingent on receipt of approvals, financing, and other standard conditions) may help push close calls in the applicant's favor. Taking other steps to develop the project–obtaining the rights to an appropriate project site, signing gas supply agreements, securing pipeline access–also should be helpful.

Attracting a creditworthy customer means that the project will likely also eventually be able to attract project finance, gas supply, and reputable contractors and is evidence that a project is "real." After all, regulators may be cautious about granting an authorization for a project that has attracted no customers, contractors, or capital.

In the end, receipt of a DOE authorization is necessary but not sufficient to put in service an LNG export project. Other issues such as access to gas supply, facilities siting and approvals, financing, and variations in projected worldwide LNG demand and market prices confront market sponsors even if an export license is approved.18

Perhaps the biggest concern among LNG export supporters–and the greatest hope of opponents–is that regulatory delay may result in lost opportunities as LNG customers seek more certain prospects elsewhere. The best means of minimizing the commercial risk resulting from delay, however, is to begin the FERC prefiling process, continue developing the project, and secure long-term customers.

Taking these steps in parallel not only may improve the likelihood of obtaining a favorable decision on an applicant's non-FTA export authorization, but will also enable applicants to lock in customers during current favorable market conditions and reduce the time needed for commercial launch of the project.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Jessica Fore and Kyle Wamstad for their assistance in preparing this article.

References

1. Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Outlook 2013 Early Release, Table 134. Natural Gas Imports and Exports (2012), projecting 2020 as the year the US will become a net exporter of natural gas.

2. Sabine Pass Liquefaction LLC, FE Docket No. 10-111-LNG, DOE/FE Order No. 2961, p. 28; May 20, 2011; "Sabine Order."

3. Mexico and Canada also import large volumes of natural gas from the US though these transactions are made primarily through cross-border natural gas pipelines.

4. Sabine Order, pp. 27-29.

5. Macroeconomic Impacts of LNG Exports from the United States, NERA Economic Consulting, Dec. 3, 2012, http://www.fossil.energy.gov/programs/gasregulation/reports/nera_lng_report.pdf.

6. Office of Fossil Energy, Department of Energy, Notice of availability of 2012 LNG export study and request for comments, 77 Fed. Reg. 73627, 73628; Dec. 11, 2012; "DOE/FE Comment Notice."

7. In inviting comments on the NERA study, DOE specifically requested comments to address "the impact of LNG exports on: domestic energy consumption, production, and prices, and particularly the macroeconomic factors identified in the NERA analysis, including Gross Domestic Product (GDP), welfare analysis, consumption, US economic sector analysis, and US LNG export feasibility analysis, and any other factors included in the analyses…. [including] the feasibility of various scenarios used in both analyses." DOE Comment Notice, 77 Fed. Reg., p. 73629.

8. Office of Fossil Energy, Department of Energy, Procedural Order, FE Docket No. 10-161-LNG, et al. p. 2; Jan. 28, 2013.

9. Expedited LNG for American Allies Act of 2013, S. 192, 113th Congress (2013). See also H.R. 580, 113th Congress (2013).

10. Sen. Ron Wyden, "Getting natural gas right a priority," The Hill (Feb. 5, 2013), http://thehill.com/opinion/op-ed/281281-getting-natural-gas-right-a-priority.

11. DOE Comment Notice, 77 Fed. Reg., p. 73629.

12. Sabine Order, pp. 32-33.

13. Section 15(b) of NGA, 15 USC. §717n(b).

14. Sabine Order, p. 28.

15. Coalition for Responsible Growth and Resource Conservation, et al. v. FERC, No. 12-566, 2012 US App. LEXIS 11847 (2d Cir. June 12, 2012).

16. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 3, Scoping Comments, FERC Docket No. PF12-16-000, p. 2; Nov. 15, 2012.

17. Office of Fossil Energy, Department of Energy, Energy Department Releases Study on Natural Gas Exports, Invites Public Comment, Jan. 29, 2013, http://www.fossil.energy.gov/programs/gasregulation/LNGStudy.html.

18. See, e.g., John E. Paisie, "US LNG Export Projects-1: Three-point system compares US LNG export projects," Oil & Gas Journal, Dec. 3, 2012, p. 116.

The authors

Steven Miles ([email protected]) is the energy chair and head of the LNG practice at Baker Botts; he is based in Washington, DC. Miles holds a BA (summa cum laude; 1980) in economics and psychology from Union College, Schenectady, NY; an MBA (1984) from Cornell University, and a JD (1984) from Cornell Law School, where he served as editor of the Cornell Law Review.

Thomas Eastment ([email protected]) is the head of Baker Botts' Energy Regulatory section; he is based in Washington, DC. His practice focuses on litigation and regulatory policy in energy. Eastment holds a BChE (summa cum laude; 1972) from Manhattan College, New York, and a JD (1975) from the University of Michigan Law School.