Prospects for US crude exports to Asia are looking up

Gabe Collins

China SignPost

Houston

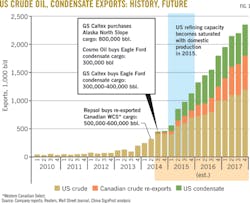

Within the next 3 to 4 years, the US can become an oil and condensate exporter capable of making available to the world market more than 1.5 million b/d of domestic crude and condensate along with 500,000-600,000 b/d of re-exported Canadian crude-a total liquids export volume on par with Kuwait (Fig. 1). East Asian buyers already show interest and have purchased all of the initial US crude and condensate export cargoes.1

At present, refiners purchase "price advantaged" crudes stranded by export controls then sell refined products at prices linked to higher priced seaborne benchmarks. This state of affairs will be increasingly unsustainable in political terms. With the Republican Party picking up at least seven Senate seats in the recent midterm elections, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alas.) will assume the Senate Energy Committee chairmanship after Jan. 1. Legislation to overturn the ban becomes more likely.

All elements other than politics are in place for a US crude export boom, and the politics will likely shift rapidly as refineries become able to absorb fewer of the domestic barrels coming onto market.

So long as realized prices for US shale production exceed $75/bbl, supply should be able to sustain exports on the scale projected in Fig. 1. Continued turmoil in Iraq-the primary source of net global oil supply growth outside of the US and Canada-could push the US export volume higher.

The chaos wrought by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in Iraq shows itself in drilling data, as Iraq's operating rig count fell to 74 rigs in August 2014 and only 58 rigs in September from an average of 91 rigs from January to July 2014.2

Sustained operational disruptions of this type will prevent or at least substantially delay Iraq from realizing its oil export potential and disturb buyers, especially refiners in Japan and South Korea, that depend on Middle Eastern crude for the bulk of supply. Such disruptions open corridors of opportunity for crude exports from the US and Canada to gain market share in Asia-Pacific, as well as Europe.

Under these circumstances, it is unsurprising that between July and October 2014, Japanese and South Korean buyers seized the opportunity to obtain US crude oil and condensate cargoes (Fig. 1).

US crude availability

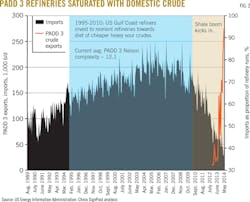

US refineries are tight-lipped about how close they are to "hitting the wall" and being unable to run additional domestic light sweet barrels. That said, data from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) for Petroleum Administration for Defense District (PADD) 3 (US Gulf Coast) refinery runs suggest that refineries began to experience constraints in late 2012 when imports fell to less than 50% of total crude supplies to refineries, resulting in a surge of exports from PADD 3 to PADD 1 (US East Coast) and Canada (Fig. 2).

PADD 3 refiners have been able to decrease imports as a proportion of total barrels run further but now seem to be hitting a wall that comes when domestic crudes account for 60% or more of supplies to a given set of plants. (See OGJ, June 2, 2014, p. 96 for definitions of PAD districts.)

Inventory draws may temporarily distort the picture, but viewed at the 3-4 month level, the fact that PADD 3-home to the largest and most complex refining capacity in the world-appears to have tested a maximum import substitution threshold at around 65% domestic crude/35% imports. The apparent limits near this threshold suggest continued domestic oil production gains will increase pressure for allowing unrestrained crude oil exports.

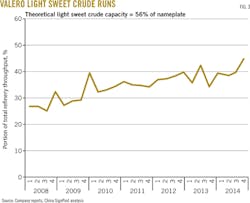

The combination of physical and-equally importantly-economic barriers helps create a pressing need for allowing US crude oil exports. Valero Corp., the largest US refiner by throughput capacity, claims to be able to use light sweet crude for 56% of its total supply. Yet in practice the company's own data show that it has struggled to run more than 40% light sweet crude in its system (Fig. 3).

US shale crudes

The period 2010-14, in which tight oil and shale crudes replaced light sweet imports, has basically run its course in PADD 3. Now, the question is how much more light sweet domestic crude can refiners in PADD 1 and PADD 5 (US West Coast) absorb before they reach economic and physical process limits?

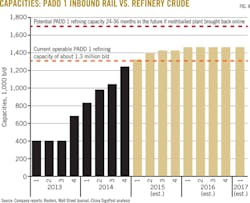

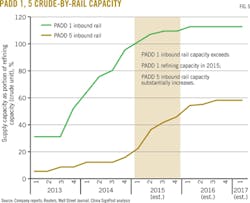

While the dynamic crude oil markets and complexity of refinery operations make a definitive answer difficult, we can infer much from the inbound rail capacity being built in both PADDs 1 and 5, which unlike the Gulf Coast have poor access to crude oil pipelines. A range of company and media reports assessing the crude-by-rail offloading terminal buildouts in both districts suggests that by mid-2015 inbound crude-by-rail capacity will exceed actual refinery distillation capacity in PADD 1 (Fig. 4).

Some rail projects aim to bring in heavy sour Canadian crudes, but most focus on light sweet shale crudes, especially from the Bakken. Potential crude supply exceeding actual refinery capacity strongly suggests in 2015 PADD 1 will become saturated and can no longer absorb additional domestic light sweet crude production growth.

Over the longer-term, mothballed refining capacity could be restarted to absorb some inbound crude, but this capacity-roughly 350,000 b/d-would likely be overwhelmed by production growth by the time the capacity actually came back online.

PADD 5 is the last frontier for absorbing additional US domestic crude production. PADD 2 (US Midwest), nearest to the Bakken and Midcontinent, saturated first, PADD 3 is now close to saturation, and PADD 1 will likely be saturated by third-quarter 2015 if oil prices remain high enough to sustain production growth at or near the current rates. PADD 5's rail coverage will likely increase substantially in 2015 but will not near saturation until as late as 2016 or into 2017 (Fig. 5).

PADD 5 does not require full rail coverage to saturate its ability to process light sweet crude. Refineries in the region-especially in California-are nearly as complex as their Gulf Coast cousins and prefer a diet of heavier, more sour crudes. EIA and Oil & Gas Journal data from 2011 (OGJ, Dec. 3, 2012, p. 32) peg PADD 5's Nelson complexity index at 10.7, second only to PADD 3's 12.1. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect West Coast refiners to begin hitting constraints if light sweet supplies rise to about 60% of total crude input.

Unlike PADD 3, which is deeply pro-energy development, PADD 5's domestic crude supply projects face major political risks. In the past year alone, at least two projects in Northern California have faced lawsuits seeking their halt, and in Washington state, the city council of Vancouver, Wash., voted against Tesoro's massive 360,000-b/d Vancouver Energy crude-by-rail facility.3

In most failed legal challenges thus far, the opponent of greater crude-by-rail activity has lost on procedural grounds, not on decisions based on the merits of the cases.4 These groups are well-funded and learn quickly, raising the risk that permits for future projects may face much longer delays than are at present expected.

Indeed, rail shipments of crude oil to InterState Oil's terminal near Sacramento were recently halted following a legal determination that the Sacramento Metropolitan Air Quality District erred in issuing the site an air quality permit without a full environmental impact review.5 This will likely drive further crude movements from the Midcontinent to the US Gulf Coast and East Coast, where refinery saturation makes legalizing crude oil exports increasingly imperative.

Asian markets

US crudes have several competitive strengths and weaknesses in the highly dynamic and competitive East Asian market.

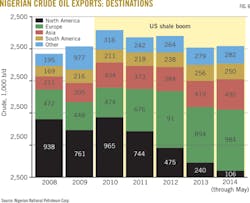

First of all, even though Japanese, South Korean, and Chinese refiners tend to prefer heavier, more sour grades, there is clearly room to blend in substantial light sweet crude as economics dictate, particularly during the summer when refiners favor gasoline supplies. Nigeria currently ships 400,000-500,000 b/d of crude to Asia (mostly to India), as shown in Fig. 6, and Angola moves substantial contract volumes into China.

Second, US light sweet crudes can be blended with heavy sour Canadian grades and exported as a synthetic crude oil grade that mimics API gravity (31-33) and sulfur content (~1.25-1.50%) of Basrah Light, ESPO (Russia), Arab Medium, and Iranian medium grades, which are staple feedstocks for East Asian refiners.6

Third, and perhaps most importantly, US crude exports will be the global swing barrels. As such, East Asian crude buyers will likely be able to use the threat of supply sourcing from the US to help reduce the "Asian premium" currently assessed against them by Middle Eastern sellers. Indeed, Saudi Arabia is at present sharply reducing its crude oil prices to Asian buyers, with the steepest price cuts occurring in the light grades that more directly compete with light sweet supplies, which are more plentiful owing to displacement of West African supplies from the North American market.7

If more substantial US export volumes are allowed-particularly blends with heavy sour Canadian crudes-the bread and butter Saudi and other Persian Gulf crudes could face unprecedented price competition in Asia 2-3 years hence. In short, gulf barrels will be the baseline supply, but US barrels are likely to be the marginal price setters.

New breed of exporter

The US will not become a "Saudi America" baseline supplier. Rather, it will be a type of crude exporter the world has not seen before: a massive producer with superb domestic pipeline, rail, and storage infrastructure that can support large-scale imports and exports; the world's largest and most complex refining industry; and hundreds of domestic oil producers large enough to export crude.

Unlike such places as Saudi Arabia, Iran, Nigeria, or Kuwait, where one monopoly producer and exporter driven by government mandates conducts all export activity, buyers seeking US crudes will have a range of producers and midstream infrastructure providers with which to deal. If Washington finally allows more liberal export policies, US crude export levels are also likely to be highly sensitive to prices and demand in the domestic market, with some months seeing large exports and others much less. Traders rather than oil ministries will drive the flow and the US will be a nimble, market-sensitive oil-producer and exporter: a battleship that turns like a corvette.

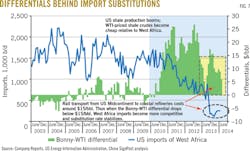

As shown in Fig. 7, US refiners already obtain crude opportunistically based on transport costs and pricing differentials. For instance, as early as first-half 2013, East Coast refiners turned away Bakken barrels when Bonny crude became cheaper than WTI and imported instead. Indeed, Phillips 66 told shareholders in second-quarter 2013 that "we have reduced our take on the Bakken to the East Coast as we have adjusted our crude slates and replacing that with more competitive barrels from imports."8

Ultimately, US crude exports will perform a market clearing function. Even if exports are allowed, producers will still look to domestic markets first and be much more flexible when allocating crude oil and condensate exports than when shipping LNG abroad because the crude oil facilities are much lower in cost per unit of capacity.

For instance, Tesoro Corp.'s Vancouver, Wash., crude-to-rail facility with marine access is projected to cost $0.5 million/1,000 b/d of capacity, while Cheniere projects the first four trains of its Sabine Pass LNG export facility will require a capital expenditure (capex) of $22.7 million/1,000 boe/d.9

Despite public opposition to exports, US refiners are rapidly preparing for a future when crude oil exports are allowed. Most publicly traded US independent refiners have created midstream-focused limited partnerships and are investing far more capital in oil transport infrastructure-pipelines, railcar fleets, storage capacity-than they are in allowing their plants to run additional light crude barrels.

For instance, Valero has 45% of its 2014 capex program dedicated to logistics, but only 27% slated for light-crude oriented refining investments, according to its July 2014 investor presentation. Phillips 66 has an even more lopsided apportionment between refining and crude oil handling in its 2014-16 capital spending budget, as shown in recent disclosures to investors.

Investing in crude gathering and transport infrastructure helps refiners secure price-advantaged crude feedstocks as long as exports are restricted, but such investing also positions those refiners to make money from moving crude to coastal export points if and when the ban is lifted. When US crude can finally move directly to world markets, refiners in Japan, South Korea, and possibly China, will be among the first in line to buy.

References

1. Berthelsen, Christian, and Friedman, Nicole, "Conoco Ships Alaska Oil to South Korea as Exports Climb," The Wall Street Journal, Sept. 30, 2014.

2. "Rig Count," Baker Hughes, http://www.bakerhughes.com/rig-count.

3. Larrabee, Jared, "We Remain Committed to the Process," Vancouver Business Journal, June 13, 2014.

4. See, for example; Carroll, Rory, and Chaussee, Jennifer,"UPDATE 1-California judge throws out lawsuit targeting crude by rail facility," Reuters, Sept. 5, 2014.

5. Bizjack, Tony, and Tate, Curtis, "Sacramento crude oil transfers halted; air quality official says permit was granted in error," Sacramento Bee, Oct. 22, 2014.

6. For detailed discussion of crude blending potential, see Auers, John R., "The North American Crude Boom: How Changing Quality Will Impact Refiners," Mar. 1, 2013, http://www.turnermason.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/North_American_Crude_Boom-platt-2013.pdf.

7. "Saudi Aramco continues to slash crude prices to Asia," Platts, Oct. 1, 2014.

8. "Phillips 66's CEO Discusses Q2 2013 Results," Earnings Call Transcript, July 31, 2013, http://seekingalpha.com/article/1589702-phillips-66s-ceo-discusses-q2-2013-results-earnings-call-transcript.

9. Culverwell, Wendy, "Unions back Vancouver Energy's oil terminal," Oct. 17, 2014, http://www.bizjournals.com/portland/blog/sbo/2014/10/unions-back-vancouver-energys-oil-terminal.html?page=all. See also Cheniere Energy Investor Presentations, http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=101667&p=irol-presentations.

The author

Gabe Collins ([email protected]) is a Permian basin native who cofounded China SignPost in 2010. Based in Houston, he conducts primary research in Mandarin, Russian, and Spanish, with analysis that spans multiple global commodity classes, with a particular focus on conventional and unconventional oil and gas development in China, the former Soviet Union, the US, and Mexico. Collins holds a BA from Princeton University and a JD from the University of Michigan Law School and is a member of the International Association for Energy Economics.