Drive for oil exports pushes East Africa pipeline development

Brendon J. Cannon

Kisii University

Nairobi

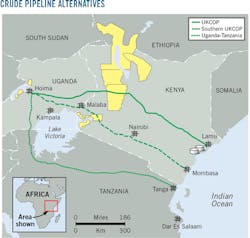

The proposed Uganda-Kenya Crude Oil Pipeline (UKCOP) across northern Kenya, one of three new liquids pipelines planned for the region, is already having major effects and unintended consequences even as it attempts to meet producers' demand for export solutions.

UKCOP is one of two crude oil pipelines planned for construction in East Africa. Should either be completed, crude would flow from Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, and possibly South Sudan and Ethiopia to various Indian Ocean ports for export to China, South Asia, and other markets, reversing a history of imports. The third pipeline would ship refined products inland from the coast.

UKCOP

The 932-mile Uganda-Kenya Crude Oil Pipeline is designed to carry oil produced in Uganda and Kenya across northern Kenya to the Port of Lamu. The pipeline will follow a northern route from Hoima on the shores of Lake Albert in western Uganda, across Kenya through Kainuk and Lokichar in Turkana County, proceeding to Isiolo and Garissa, and ending at Lamu on the Indian Ocean.

Planning of the proposed pipeline, stretching 404 miles through Uganda and another 528 miles in Kenya, has been underway for years, spurred by the discovery of commercial oil reserves in Uganda in 2006 and Kenya in 2012. Kenya's reserves remain unproven, though Tullow Oil PLC estimated that production there could reach roughly 100,000 b/d. Estimates of Uganda's petroleum reserves have grown rapidly, from 300 million bbl in 2006, to 3.5 billion bbl of commercially viable oil in 2012, and 6.5 billion bbl in 2015, of which at least 1.5 billion bbl is recoverable, according to Ugandan government estimates. There is also significant scope for further growth, as only 40% of Uganda has been explored so far.

Northern route

A deal struck in August 2015 between Kenya and Uganda called for building the UKCOP along the proposed northern route, subject to financing, transit fees, and security guarantees by Kenya. This decision, however, based on a feasibility study carried out by Toyota Tsusho Corp., Nagoya, Japan, is not without controversy. A number of multinational oil companies instead support a southern route through central Kenya. This route would run closer to an existing oil pipeline ending at the Port of Mombasa.

Kenya's government openly favors the proposed northern route as it fits into its integrated Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) corridor, a massive transport and infrastructure project. UKCOP is the lynchpin project of the LAPSSET corridor, which includes a new port in Lamu, an airport, highway, rail line, and an oil refinery, at an estimated combined cost of more than $22 billion. The selection of the northern route could have major geopolitical significance as it will eventually enable South Sudan to pump crude oil to Lamu Port. South Sudan would no longer be dependent on Sudan to transport its oil, thus denying its northern rival major transit revenues and ending Sudan's effective control of South Sudan's oil exports.

Pipeline cost, details

Toyota Tsusho estimates UKCOP will cost about $4.7 billion. Annual operating expenses are estimated at roughly $131.5 million. The Kenyan government estimates that the pipeline will be completed by 2018 or 2019, should funding be available.

Design throughput is 300,000 b/d: 200,000 b/d from Uganda and 100,000 b/d from Kenya. Plans call for the crude from Uganda and Kenya to be blended for transport. The pipeline will have a smaller diameter between Uganda's oil-rich Kaiso-Tonya area, west of Hoima, and Lokichar, Kenya. A larger diameter would run from Lokichar to Lamu Port to accommodate Kenya's oil.

The waxy nature of the oil in both countries-it remains solid below 104° F. (40° C.)-requires heating the proposed pipeline and using multiple pump stations. UKCOP would be the longest heated crude oil pipeline in the world. Kenya's government has announced that the still-to-be-awarded pipeline design contract will include a fiberoptic cable from Uganda's oil fields to Lamu and tank terminals in Hoima, Lokichar, and Lamu. The project will also include a 5.5-mile pipeline from the Lamu tank terminal to an offshore loading buoy. The Kenyan government previously stated that bids for the construction of the pipeline would be invited in second-half 2015 but no announcements have been made.

The current plan as envisaged by Toyota Tsusho allows for an additional 130,000 b/d from South Sudan under a high-flow scenario. If the pipeline is extended to South Sudan, there will be a total of seven pumping stations along its route, with three in Uganda and two in Kenya, including the injection pump at Lokichar, Kenya.

Development potential, problems

Projects associated with the LAPSSET corridor will potentially open large swathes of land to development that has traditionally been reserved for the more southerly, Mombasa-Nairobi-Kampala corridor. The project aims to increase access to government services, augment regional trade, improve existing economic links, and foster new ones. Once completed, the LAPSSET corridor and UKCOP have the potential to reduce transportation costs, uphold peace and security, and foster development, as well as create business opportunities for communities adjacent to the corridor.

Yet the politics of successfully bringing the LAPSSET corridor to fruition remain problematic. It is unclear exactly how much communities surrounding the transport corridor and pipeline will benefit. Precisely where and how the roads, pipelines, and other infrastructure-related projects will be built and whose land they will cross also still needs to be hammered out.

The effects of discovering oil in the Turkana region of northeastern Kenya on local populations remains uncertain. A recent upsurge in violence between tribes in this region may result directly from oil's discovery, inspiring attempts by individuals and groups to establish control of land surrounding potential oil fields.

Security concerns

Concerns also exist about the general lack of security along the proposed northern corridor pipeline route in Kenya. Perhaps the biggest security threat comes from the Somali terrorist group, al-Shabaab, which has attacked targets ranging from the Westgate Mall in Nairobi and Garissa University to small, isolated villages around Lamu. Projects associated with the LAPSSET corridor would likely serve as tempting, symbolic, and economically damaging targets. Tullow cited this in initially supporting a UKCOP route through Nairobi. Regardless of where the pipeline is eventually built, Tullow remains adamant it be constructed as a joint venture between Kenya and Uganda to capitalize on its oil reserves in both countries.

Total SA, on the other hand, and its various subsidiaries, including Total E&P Uganda, have suggested an alternative route, stretching from Hoima in Uganda via northern Tanzania to the Port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean, bypassing Kenya completely. While this proposal was initially ignored by both Kenya and Uganda, Uganda is now exploring the possibility of such a pipeline with Tanzania.

Politics

Kenya and Uganda, in an effort to spur UKCOP's construction, are establishing an oil company to be owned by all stakeholders involved in the pipeline. The framework of the proposed company, its location, recruitment processes for management, and shareholding will be overseen by the Kenya-Uganda committee on the crude oil pipeline. It will be a joint venture, owned by Uganda, Kenya and oil investors in both countries.

Uganda's government also set three conditions for agreeing to participate in the pipeline:

• Kenya must guarantee it will offer Uganda cheaper transit fees via the northern route than alternative routes.

• Kenya must provide security along the pipeline.

• Kenya and Uganda must agree on financing.

It is unclear how Uganda or Kenya will determine "cheaper fees" for the northern route in comparison with those of alternative routes. Kenya also cannot fully know transit costs until the front-end engineering and design (FEED) is completed.

The costs associated with Uganda's pre-conditions come in addition to the fact that each of the countries associated with the project is responsible for developing the route under its jurisdiction. Kenya, with the longest section, will contribute the largest part of the $4.7 billion budget.

UKCOP's principals expect Tullow Oil, Total, China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC), Africa Oil Corp., and Ugandan oil companies to mull the proposed route, ask for any potential concessions, and make a final investment decision by October 2017. But Total's proposal and recently signed memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Tanzania and Uganda make its hesitance clear.

Adding further confusion, Ethiopia has announced plans with Djibouti to build a 550-km pipeline that would be an alternative to any pipeline constructed through northern Kenya, undercutting the LAPSSET corridor's rationale.

Mombasa-to-Nairobi pipeline

A new 20-in. OD, 280-mile petroleum products pipeline from Mombasa to Nairobi is under construction. Built by Kenya Pipeline Company (KPC), this pipeline replaces an existing 35-year old line.

Work on the new pipeline began in 2012 when KPC commissioned China's Sheng Li Engineering and Consulting Co. Ltd. and Kenya's Kurrent Technologies to design it and plan its construction. Lebanon's Zakhem International Co. is building the pipeline.

Kenya's economy has been growing rapidly for the past 10 years: 5.4% on average from 2004 to 2015, with a peak of 12.4% in fourth-quarter 2010. This growth has increased liquid fuel demand and heightened the need for larger and better fuel storage and pipelines. Kenya has no strategic product reserves and relies on the 21-day reserves marketers must keep under industry regulations. The larger storage site being built in Nairobi should help reduce import delays.

Demand is also rising in Kenya's neighbors: Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, which have suffered from persistent fuel shortages for years. Refined products are trucked to Kenya's land-locked neighbors from the Port of Mombasa at great expense and under hazardous conditions. Demand from Kenya's neighbors was 2.4 billion l./year in 2010 and rose to 2.8 billion l. in 2014, stretching KPC's storage to its limits.

In addition to creating supply inefficiencies, the lack of sufficient storage costs Kenya revenue, as companies who might store products there are forced to find alternatives. The new pipeline should spur development of additional refined products storage.

Construction, capacity

The new pipeline is using the existing line's right-of-way. The project will include not only the pipeline but also laying of a 96-core fiberoptic cable from Mombasa to Nairobi. New pumps will be installed at Changamwe, Maungu, Mtito Andei, and Sultan Hamud, with two booster pumps installed at Kipevu.

The current pipeline can ship 167,000 b/d, enough to serve Kenya's needs until 2017, according to KPC. Construction of the new 20-in. OD pipeline began in mid-2015 and by August a total of 44 km of pipe stringing and 16 km of welding had been completed. KPC expects the pipeline to move 326,000 b/d by early 2017, enough to supply the entire region through 2044.

The new line will include an automatic control system and field instrumentation systems allowing for automatic operation and helping properly monitor the transportation of highly combustible products. KPC firefighting systems at Moi International Airport, Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, and Kipevu will also be upgraded.

A 10-in. OD pipeline running 76 miles from Sinendet in Nakuru to Kisumu, on the shores of Lake Victoria, will complement the larger line. The line will increase capacity along the route by 72,000 b/d, alleviating regular product shortages in Kisumu caused by limitations of the existing 6-in. OD pipeline, built in 1992. The new line will operate simultaneously with the existing one.

Uganda-Tanzania

Uganda is looking at pipeline construction separate from UKCOP. Uganda also is attempting to keep its options open and have governments and oil companies compete for its oil. It is considering Total's proposal to build a 960-mile crude oil pipeline from Hoima, Uganda to Tanga, Tanzania, bypassing Kenya, and in October 2015 signed an agreement with Tanzania to study the pipeline. The two countries wish to identify the lowest cost option for transporting their export crude, following the MoU signed by Uganda, Tanzania, and various international oil companies, including Total E & P Uganda and Tanzania Petroleum Development Corp. (TPDC).

This pipeline would travel the western shore of Lake Victoria, cross northern Tanzania, and end at the Port of Tanga, on Tanzania's northeastern Indian Ocean coast, near its border with Kenya. Tanga is the second largest port in Tanzania after Dar es Salaam, but is underused and unable to handle large cargo volumes. Its 2013 capacity was 500,000 tons, of which just 76.5% was used. The Tanzania Ports Authority in 2011 allocated $600 million for construction of the new Mwambani Port at Tanga, but lack of demand has delayed its construction.

But the Uganda-Tanzania option would cost an estimated $5.26 billion compared with UKCOP's $4.7 billion.

Pipeline geopolitics

The Tanga pipeline announcement has ruffled feathers with the Kenyan government, given Uganda's previous commitment to work with Kenya to build a pipeline. The announcement also appears to have caused a rift between major oil companies operating in the region. Africa Oil Corp. publicly stated that the only viable option was a joint pipeline running through both Uganda and Kenya, putting it and its larger partners, Tullow and CNOOC, at odds with Total and potentially Uganda. Only once a pipeline is built to the Indian Ocean can exports begin, and the three companies were counting on UKCOP being available as soon as possible.

While the agreement between Tanzania and Uganda is a victory for Total, which had made clear its security and terrain-based reservations regarding UKCOP's northern route, it threatens potential investment in northern Kenya. UKCOP's demise could spell the end of LAPSSET, including construction of Lamu Port, loosening the potential ties between Kenya, South Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda, and Ethiopia. But Tanzania will remain outside the current oil boom without the southern spur favored by Total.

Bibliography

Africa Oil Corporation, "Operations Update: 2015 Third Quarter Update," http://www.africaoilcorp.com/s/operations-update.asp.

Gridneff, I., "Africa Oil Sees Joint Pipeline as Only Option for Uganda, Kenya," Bloomberg Business, Nov. 10, 2015.

Hatcher, J., "Kenya Oil Deposits Fuel Inter-Communal Conflicts," Voice of America, Feb. 2, 2015.

Johannes, E. M., Zulu, L. C., and Kalipeni, E., "Oil discovery in Turkana County, Kenya: a source of conflict or Development?," African Geographical Review, Vol. 34, No. 2, February 2015, pp. 142-164.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, "Kenya GDP Annual Growth Rate," Trading Economics, 2015, http://www.tradingeconomics.com/kenya/gdp-growth-annual.

KPMG, "Oil and Gas in Africa: Reserves, Potential and Prospects of Africa," KPMG Africa Ltd, 2014

Khan, K. A., "Uganda-A Country yet to Achieve its Entity: Discovery of Oil and Future Prospects," Development, Vol. 2, No. 4, April. 2015, pp. 16-24.

Ligami, C., "Total's bid for a Tanzania pipeline route rejected," The East African, Sept. 19, 2015.

Lund, S., "Political Regionalisation and Oil Production in Africa: The Case of the LAPSSET Corridor," MA thesis, Stellonbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2015.

Mbanga, J., "Tanzanian route throws race for Uganda's oil pipeline wide open," The Observer, Oct. 15, 2015.

Musoke, R., "Fight over oil pipeline, "The Independent, Oct. 26, 2015.

Ochieng, L., "Kenya and Uganda to establish company to manage crude oil pipeline," Daily Nation, Sept. 28, 2015.

Ochieng, L., "LAPSSET blow as Uganda signs pipeline deal with Tanzania, Daily Nation, Oct. 13, 2015.

Olingo, A., "Tanzania, Uganda sign Tanga oil pipeline agreement," The East African, Oct. 13, 2015.

The East African, "Tanzania to expand Dar, Tanga ports," Nov. 13, 2011.

Van Alstine, J., Manyindo, J., Smith, L., Dixon, J., and Amaniga Ruhanga, I., "Resource governance dynamics: The challenge of 'new oil'in Uganda," Resources Policy, Vol. 40, June 2014, pp. 48-58.

The author

Brendon J. Cannon is a professor at Kisii University, Nairobi, and the director of Gollis University Research Institute in Hargeisa, Somalia. An academic researcher, lecturer, and freelance journalist, much of his work focuses on geopolitical implications of resource extraction and major engineering projects, particularly in East Africa, Central Asia, and the Middle East. He earned his Ph.D (2009) in political science from the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.