Politics, NOCs drive China’s uncertain LNG market

Batt Odgerel

William Pack

Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc.

Washington, DC

China’s potential as a very large LNG demand center remains uncertain. Estimating long-term LNG demand from China faces two unique problems. First, China is a very large consumer of natural gas supplied from both domestic production and overland pipelines, as well as LNG. Understanding the interrelationship between these supply sources is not straightforward. Second, because of the size of the Chinese market, relatively modest shifts in national priorities and government policy can have an outsized effect on LNG demand in Asia, leading to volatility in both prices and supply patterns.

This article examines China’s role as a demand center for LNG and evaluates how a range of conditions and policy initiatives could change the scale and scope of China’s demand profile in the Asian LNG market.

Background

A small change in the Chinese natural gas sector can lead to an oversized impact on global markets. China’s coal-to-gas switching policy led to a spike in spot Asian LNG prices in winter 2017. The resulting opportunity for arbitrage attracted an unprecedented number of LNG vessels from the Atlantic Basin to the Pacific, ushering in the beginning of a new era in the Asian gas industry.

Driven by a rising political imperative to reduce air pollution, record growth has been observed in natural gas demand in China over the past decade. China surpassed South Korea as the second largest LNG importer in 2017 and Japan as the world’s largest natural gas importer in 2018. China’s LNG import trends reflect official policy on improving air quality, concerns over energy security, the pace at which nuclear power and renewables can be deployed, and the role of domestic supplies and foreign pipeline imports.

The State Council, adhering to the guidance of the Communist Party, has put a great emphasis on natural gas in official government documents, including in its five-year plans and various “notices” and “opinions” published by the Council. Despite the absence of a unified energy ministry, the Chinese economic planning agency, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), has delivered strong results in promoting natural gas and LNG. In accordance with the 13th Five-Year Plan, the combined efforts of other state ministries as well as municipal and provincial governments are developing national policy in this area. Even with growth in natural gas pipeline imports and continued expansion of domestic natural gas production, local and national policies will drive rising demand for LNG. Small scale LNG, expansion of LNG storage capacity, and the political imperative to improve air quality will likely drive LNG imports from 71.6 billion cu m/year (bcmy) in 2018 to 119 bcmy by 2020.

Beneath China’s bureaucracy lie more autonomous and commercialized state-owned oil and gas groups: China National Petroleum Co. (CNPC), China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. (Sinopec), and China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC). These monopolistic enterprises are responsible for all domestic gas production and natural gas imports by pipelines and fully or partially own more than 90% of total LNG receiving capacity in China.

Against this backdrop, the NDRC and local governments pursued more competitive market policies, prompting the emergence of so-called second-tier players. Public utilities and private enterprises have begun engaging in the LNG business by leasing receiving terminals or building their own. These second-tier players are advancing their presence in unconventional technologies such as small-scale LNG and LNG trucking. Independent entities are also engaging in spot markets to a greater extent than in the past, but only account for a small portion of total Chinese LNG demand.

Air pollution in large cities has been the main cause of China’s insistence on crafting a long-term clean energy policy. In the short run, however, seasonal fluctuations, especially winter temperatures, have had a direct impact on household consumption and the movement of LNG vessels.

China has shale gas reserves that could dwarf those in the US. Due to technological barriers, geological difficulties, and lack of investment, however, China’s NOCs have not been able to tap this potential. Unless major breakthroughs occur in shale gas, growth in domestic production will likely remain modest and lead to a growing dependence on LNG and pipeline imports.

China’s natural gas policy can be divided into three components: substantial growth in natural gas use, security and stability of supply, and market-based reforms. Growth in natural gas use and LNG imports is projected to stay on track, but the 13th Five-Year Plan’s goal to raise the share of natural gas in the energy mix may fall slightly short of its target. This is largely due to China’s insufficient growth in domestic output, the stalling of pipeline projects, and the country’s overall limited upstream capacity. Imports are expected to meet nearly half of total demand by 2020, with LNG driving that growth before the expected moderating effects of new pipeline projects such as the Power of Siberia.

About four million households switched from coal to gas or electricity for heating in the winter of 2017, contributing to extremely tight gas markets and high LNG prices. The transition came at the expense of societal wellbeing as some households and schools had to endure the winter without sufficient heating. To ensure supply security and stability, China is increasing its storage and peak shaving capacity, particularly underground gas storage (UGS) sites and LNG receiving terminals. An improved peak shaving system will smooth out the effects of seasonal variations and help maintain a more robust LNG sector.

Although the conventional view is that spot LNG markets are on the rise, China’s share of medium- and long-term contracts in total imports has remained steady due to recent deals with companies such as Qatargas. This trend is supported by government policy to ensure national gas supply security.

China is striving towards more liberalized natural gas markets with improved pricing mechanisms, open access to infrastructure, and transparent gas trading hubs. The State Council has taken steps such as unifying residential and non-residential gas prices and has initiated policy to open third-party access (TPA) to LNG receiving terminals. China has established trading hubs in Shanghai and Chongqing to continue the liberalization of gas pricing and to set price benchmarks for Asian natural gas markets.

Despite China’s recent initiatives, Chinese gas pricing mechanisms are yet to be fully market-based and lag far behind those of the US and Europe. Domestic gas prices remain pegged to alternative fuels and long-term LNG contracts are linked to oil prices in the Asian market. Despite the first public TPA-slot auction this year, it remains to be seen whether problems stemming from a limited number of terminals and import windows can be addressed. The full maturing of Chinese trading hubs is likely to take a long time, with little international interest thus far shown.

Market environment

China’s energy policy has traditionally emphasized production of domestic reserves as opposed to relying on imports. This policy is part of the reason why the energy mix has been so focused on oil and coal, but that will change in the near future. Total proven reserves of Chinese natural gas amount to 5.52 trillion cu m and total domestic gas production was 148.7 bcm in 2017.1 Chinese natural gas consumption reached 237.3 bcm in 2017, up 15% year-on-year.2 Domestic production is still able to meet most of the nation’s consumption, but as China replaces coal and oil in the energy mix, it will need to increase imports of natural gas.

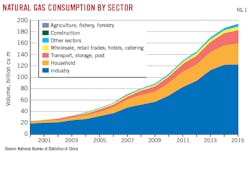

Fig. 1 shows that industry usage constituted almost two-thirds of total consumption in 2015, followed by households (18.6%) and transport (12.3%). Mainly driven by the Chinese government’s decision that households switch from coal to gas, the country’s LNG imports increased to 38.1 million tons (42% growth) in 2017, outpacing South Korea as the second largest importer of LNG.3 The share of natural gas in total energy mix remains at 7.5%,4 with coal and oil combining for 80% of total consumption.1 But as state and local governments continue to promote natural gas in households, we anticipate further growth in both residential gas consumption and LNG demand.

Environment, climate factors

Environmental pollution and seasonal fluctuations play important roles in China’s natural gas sector. Air pollution prompted the country to commit to energy technologies with low emissions, and China’s environmental policies have moved to address soil and water pollution as well. Climate volatility plays a more direct role in determining short-term consumption. China’s sudden increase in demand in recent years due to colder than usual winters led to price spikes in the Asian LNG market.

Increasing social unrest and demonstrations against pollution have drawn heightened government attention. In accordance with the State Council’s 2013 Action Plan on Prevention and Control of Air Pollution,5 China plans to reduce total coal power capacity below 1,100 Gw by 2020. The number of smoggy days in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei area dropped from 71.1 in 2013 to 42.3 in 2017.6

Policy implementation

China’s natural gas and LNG policy are directly linked to environmental and clean energy efforts reflected in the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016- 2020) and documents such as the 2018 Action Plan to Win the Battle for Blue Skies (Table 1). The 13th Plan states that an increase in the share of natural gas in the country’s energy mix is “the only way” to create a clean, efficient energy system. The document proposed to increase the share of natural gas in the total energy mix to 10% from 6%, while decreasing coal to 58% from 64% between 2015 and 2020.

Internationally, China pledged to make natural gas one of its main energy sources by 2030 in accordance with UN sustainable development goals.7

Projections through 2020

A combination of slow development in domestic unconventional production and delays in implementing pipeline import projects will likely keep natural gas’s share of the total energy mix below NDRC’s 2020 target. Future consumption and LNG imports are contingent upon natural gas infrastructure development, including LNG terminals. China projects the share of natural gas in its energy mix to increase to 8.3-10.0%, 353-391 bcmy, provided it manages to limit its annual energy consumption to five billion tons standard coal equivalent (3% annual growth) by 2020. For this, China must achieve 13.3% annual average growth in its gas demand from the 2015 level of 193.1 bcm. Real demand is projected to fall short of this by 2.4 percentage points, with 2018 consumption estimated at 263.5 bcm.8 In other words, Chinese consumption in 2020 is projected to be 325-330 bcm, slightly below the national target.

In 2016 and 2017, the annual average growth of domestic gas production was only 5%. As of October 2018, China had produced 129.5 bcm, up 6.9% from the same period a year earlier. Given the lagging historical performance of natural gas production growth, it is likely that domestic output will not exceed 179.3 bcm in 2020 as contrasted to the five-year plan’s projection of 207 bcm. Pipeline imports will likely sustain their recent growth rate and reach about 48.3 bcm in 2020. If completed in late 2019, however, the Power of Siberia pipeline is expected to add up to 5 bcm of imports in its first year. Given that domestic natural gas growth has been lagging, there is an opportunity to fill the anticipated 2020 supply gap of 119 bcm (88 million tons) with LNG.

US export capacity at the end of 2018 was 50.65 bcmy and, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), additional US liquefaction will increase LNG export capacity to 132.62 bcmy by 2021. Much of this could be sold to China if market and political forces allow.

Imports will meet a little less than half of China’s natural gas demand in 2020, driven largely by continued growth in LNG. Shell projects that LNG will constitute 31% of growth in natural gas supply in China between 2017 and 2030, with an annual growth rate of 4%.9 This rate of growth would make China the largest LNG importer in 2030 if the Japanese government cuts its country’s LNG consumption to 62 mtpy, as currently planned. The International Energy Agency posits that Chinese demand will rise even more rapidly, reaching 67.4 mtpy (93 bcm) in 2023, an annual growth rate of 10%.

Domestic potential

China’s gas reserves are found across basins covering 4 million sq km with sedimentary rocks from the Paleozoic to Cenozoic eras. By the end of 2017 accumulated proven geological reserves were about 14.2 trillion cu m, remaining technically recoverable reserves 5.5 trillion cu m,10 and economically recoverable reserves 3.9 trillion cu m.11 The largest basins are concentrated in Tarim (Xinjiang autonomous region), Ordos (in the mid-northern provinces), Sichuan, and offshore.12 Decreased investment in oil and gas exploration has limited development of proven reserves.

In 2017, natural gas production was 148.7 bcm and the reserve-production ratio was 36:1, only a third the average of the Middle East. This could change if the three big NOCs ramp up investment. CNPC plans to invest RMB 150 billion ($22 billion) in its Tarim oil and gas production,13 which will boost the region’s 23.5-bcm 2017 output by 75% by 2020.14

Given China’s large potential reserves the State Council and state-owned enterprises (SOE) are studying shale gas and coal bed methane (CBM) extensively. The three large NOC’s 2017 shale gas and CBM production was 9 bcm and less than 3.3 bcm, respectively. Sinopec’s Fuling shale gas field in Chongqing produced 6 bcm that year.15 Wood Mackenzie estimates that drilling technology and cost cutting will boost China’s shale gas production to 17 million bcm in 2020. But this still falls short of the government’s planned 30 bcm and analysts are not betting big on Chinese shale gas in the short run.16

Pipelines, storage

Inadequate pipeline and storage capacity are important constraints limiting a more rapid expansion in natural gas consumption. Without scaling up natural gas infrastructure—pipelines, LNG terminals and storage, and underground storage—the government’s aim to amplify consumption could continue to fall prey to price hikes and winter supply shortages. The 2018 NDRC Notice on the Construction and Operation of Gas Storage Facilities, which encourages local governments to build storage, requires streamlined approval processes and construction of projects as well as improved coordination between gas storage operators and natural gas pipeline networks.

China’s natural gas trunk pipeline system has expanded 6.4 times in the past 20 years, from 11,000 km in 1998 to 70,000 km in 2017.17 The NDRC set targets to grow this length to 104,000 km by 2020 and 163,000 km by 2025.18,19

Three Central Asian countries supply more than 90% of total pipeline imports: Turkmenistan, 80% (31.7 bcm), Uzbekistan (3.4 bcm), and Kazakhstan (1.1 bcm). Remaining pipeline supplies come from Myanmar (3.3 bcm). The three Central Asia-China lines (A, B, and C) have a combined capacity of 55 bcm.20 A fourth line (D) is under construction with no completion date set.21

As current pipelines near capacity limits, growth in pipeline imports depends on construction of new systems.

Russia’s Power of Siberia is expected to deliver 38 bcmy to China via its eastern route for 30 years starting December 2019. If the project comes online as scheduled it will moderate LNG growth 2020-24.22 Power of Siberia II, a 30-bcmy project to supply gas to western China via the Altai Mountains, has been stalled since CNPC signed a heads-of-agreement with Gazprom in 2015.23 China in recent months, however, has shown renewed interest in advancing the project.

After the price volatility in the winter of 2017, the NDRC identified greater investment in storage capacity as a measure to enhance natural gas supply security. The NDRC plans to promote a multi-layer peak shaving system, in which UGS and coastal LNG receiving terminals are the two main supply sources.24 Key measures include ramping up construction of gas storage and peaking facilities, establishing a natural gas reserve system, and supporting local authorities and business entities in building gas storage. An expanded peak shaving system with more UGS and LNG regasification capacity will enable increased LNG imports throughout the year.

In 2018, the working volume of China’s UGS reached 16 bcm, surpassing the NDRC target of 14.8 bcm by 2020.25 However, this capacity represents only 4-5% of total annual natural gas consumption, against the global storage average of 12-15% of consumption.26 Insufficient LNG storage capacity has also become a bottleneck to sustainable growth in China’s natural gas use.

The NDRC required NOCs to have storage equaling at least 10% of contracted sales by 2020 and town gas companies 5% by 2020.27 Of the 25 UGS sites in China, CNPC has 23 and Sinopec two. The two SOE have plans for UGS projects that could increase capacity three- to five-fold over the next decade. CNPC plans to build seven to eight storage sites with total 21.74-bcm capacity starting in 2022. Sinopec, having two UGS (Wen-23 and Wen-96) with a total working capacity of around 5 bcm,28 plans to add 55 bcm.29

LNG terminals

China’s rapid growth of LNG imports has been made possible by an increase in the number of LNG regasification terminals and associated storage. There are 20 LNG receiving terminals in China, with total design capacity of more than 62 mtpy in current configuration and additional expected capacity of 40 mtpy in subsequent phases. Total storage at these terminals is 8.6 mcm (3.9 million tonnes).30 CNOOC singly or jointly owns nine LNG receiving terminals with total capacity of 33.8 mtpy. CNPC and Sinopec own three each and ENN Energy owns the only private 3-mtpy terminal. Other second-tier companies have terminals with capacities less than 3 mtpy.

The State Council approves LNG receiving, storage, and transportation (including expansion of existing) projects.31 A proposal is first submitted to a local natural resources department and pre-examined by the Ministry of Natural Resources.32 Projects with a capacity of 3 mtpy or more are reviewed by the NDRC and submitted to the State Council for approval. Smaller projects are approved by provincial governments.31

The NDRC has relaxed its requirements for the approval of LNG receiving terminals by lowering the required-size supply agreement with an outside partner to 1 mtpy. But the approval process is still complicated. In addition to the different regional layers of agencies involved, the Ministry of Transport reviews onshore terminals and the State Oceanic Administration reviews floating storage and regasification units (FSRU).33 Of at least 30 project proposals for LNG receiving terminals only five have entered planning or received approval for construction.

China’s LNG terminal utilization rate averaged 66% in 2017, with some running above nameplate capacity.34 No major LNG terminal is expected to come online through 2020, however, so growth must depend on expanding existing terminals. It is not clear whether expected expansions will be completed in the current Five-Year Plan’s period. Total receiving capacity will reach 100-110 mtpy by 2020. At a utilization rate similar to 2017, the LNG import level in 2020 will likely be 60-70 million tonnes. SIA Energy estimates that LNG receiving capacity in China will reach nearly 200 mtpy by 2030.35

Table 2 shows proposed LNG terminals in China.

LNG pricing

In Northeast Asia, LNG contract prices are pegged to the Japan Crude Cocktail (JCC), partly as a result of the early entry and sophistication of Japanese oil and gas importers relative to those of other regional countries.

China’s supply from existing long-term contracts is expected to peak around 2020-24 and slide afterwards. This projection, however, is likely to change as Chinese companies sign some long-term deals as others approach expiration. The government is also encouraging companies to sign long-term purchase and sale contracts to maintain uninterrupted growth in natural gas consumption. China may have to increase its spot LNG purchases as incremental long-term agreements go unrenewed.

New medium- and long-term contracts were absent in 2017, importers opting instead for shorter-term 5- to 10-year deals.36 But the supply shortage and price hikes in the winter of 2017 slowed further movement in this direction. China instead sought diversification in its LNG mix by signing long-term contracts with Cheniere Energy, its first to import US LNG.

The US-China trade war has renewed China’s interest in long-term contracts as a means of both minimizing its effects and ensuring stable gas supply. China signed or extended several long-term contracts with Qatar and Australia in 2018.

LNG imports increased in the colder months of 2016, 2017, and 2018 (Fig. 2). This was most evident in early 2018, January imports nearly doubling those of 2016, due to increased spot purchases. The average monthly price of LNG surged after this. The average July 2016 LNG price was only 14% higher than pipeline gas prices, but this gap grew to 63% in July 2018 as LNG demand kept growing.

Private companies like ENN have in the past criticized the national oil companies for locking themselves into an excessive number of long-term contracts at high prices. Private companies by contrast are increasingly engaged in spot and short-term LNG markets. The resulting flexibility has impacted global LNG markets, as LNG vessels redirect their routes to the Pacific Basin when arbitrage opportunities allow.37

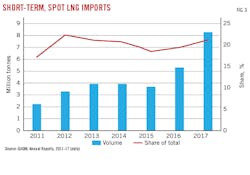

Although increased private sector participation boosts short-term and spot market trade, their share will likely remain small compared with long-term contracts. In 2017 the number of spot and short-term contract transactions increased by 56%, but its overall natural gas consumption remained close to the levels experienced between 2011 and 2016 (Fig. 3). Despite significant growth in spot LNG trade, long-term contracts are expected to continue to play a vital market role.

Trading hubs

LNG wholesale markets are generally divided into two main categories: oil-indexed and hub-based. China’s vision is to create a hub-based system reflecting market forces instead of its current system which artificially follows Asian oil markets. China created two trading hubs 2016-17.

Xinhua News Agency and the NDRC founded the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Trading Center (SHPGX) in 2016 to create a Chinese gas pricing hub in Asia. SHPGX was designed to accelerate market-based reforms in the energy sector by improving China’s natural gas pricing mechanism and deepening international cooperation. Xinhua (the largest investor with a 33% stake), the three NOCs, and six other companies invested a total of 1 billion yuan ($144.56 million).38 The center serves as a platform for spot trading in natural gas, LNG, and other products;39 trading wholesale pipeline gas in yuan/cu m and LNG in yuan/tonne.

Following SHPGX, China established the Chongqing Oil and Gas Exchange as a regional natural gas trading hub.

Taking advantage of geographic proximity, the center is expected to serve as a platform for trade in natural gas from the Sichuan basin, Central Asia, and Russia to other parts of China.40

Neither exchange, however, has generated substantial interest internationally. China continues to push the hubs to the greater market.

References

- BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2018.

- Abreu, A., “Analysis: China’s Expanding Underground Gas Storage May Reduce LNG Winter Price Volatility,” S&P Global Platts, July 31, 2018.

- Zaretskaya, V., “China Becomes World’s Second Largest LNG Importer, Behind Japan,” US EIA, Feb. 23, 2018.

- National Energy Administration [China], “Notice of the National Energy Administration on Printing and Distributing the Guiding Options on Energy Work in 2018, Mar. 9, 2018.

- State Council [China], “Notice of the State Council on Printing and Distributing the Action Plan for Air Pollution Prevention and Control,” (Chinese), Sept. 12, 2013.

- “Four Years On: Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei coordinated development,” China Daily, Feb. 27, 2018.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, “China’s National Plan on the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” Oct. 12, 2016, p. 33.

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) of Chna press conference, Oct. 23, 2018.

- Shell Outlook 2018, p. 12.

- Ministry of Natural Resources [China], “National Oil and Gas Resources Exploration and Mining Report – 2017, July 13, 2018.

- State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, “Ministry of Land Resources Holds National Conference on Oil and Gas Exploration and Mining Results,” Aug. 15, 2017.

- China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), “Ordos Basin,” http://www.cnpc.com.cn/en/xhtml/pdf/19-Ordos%20Basin.pdf

- China.org.cn, “CNPC plans 150-bln yuan investment in Xinjiang,” July 26, 2018.

- Mason, J., Hua, J., Daly, T., and Tan, F., “In China’s far west, CNPC vows $22 billion spend to replace ageing oil wells,” Reuters, July 24, 2018.

- Sinopec Group, “China’s first shale gas field hits 10 bcm/year,” Mar. 29, 2018.

- Wood Mackenzie, “Chinese shale gas production will almost double in 2 years,” Apr. 17, 2018.

- Duan, Z.F., “China Natural Gas Market Outlook,” CNPC Economics & Technology Research Institute, Nov. 8, 2017.

- Xinhuanet, “China plans to expand oil, gas pipeline networks,”July 12, 2017.

- NDRC, “Notice of Printing and Distributing the Medium and Long-Term Oil and Gas Pipeline Network Plan,” (Chinese), July 12, 2017.

- CNPC, “Flow of natural gas from Central Asia,” https://www.cnpc.com.cn/en/FlowofnaturalgasfromCentralAsia/FlowofnaturalgasfromCentralAsia2.shtml

- Asia-Plus, “Construction of Tajik section of Turkmenistan-China gas pipeline starts, says Tajik official,” Jan. 31, 2018.

- RT, “Russia to become China’s top supplier of gas soon,” Sept. 22, 2018.

- Gazprom, “Gazprom and CNPC sign Heads of Agreement for gas supply via western route,” May 8, 2015.

- NDRC, “Opinions on Accelerating the Construction of Gas Storage Facilities and Improving Market Mechanism for Gas Storage and Peak Regulation,” 2018.

- NDRC, “Notice on Printing and Distributing the Opinions on Accelerating the Use of Natural Gas,” (Chinese), July 4, 2017.

- Chen, A.Z., “Factbox: China’s underground natural gas storage facilities,” Reuters, Apr. 11, 2018.

- Bai, W.S., “NDRC holds press conference regarding natural gas production and supply,” (Chinese), State Council, Apr. 27, 2018.

- Meng, M., “China’s Sinopec starts building nation’s largest gas storage site,” Reuters, May 23, 2017.

- Xin, Z., “Sinopec boosts gas storage units,” China Daily, Aug. 9, 2018.

- Petroleum Economist, “World LNG Map: 2018 Edition,” 2018.

- State Council, “Government-Approved Investment Project Catalogue,” (Chinese), Dec. 12, 2016.

- China National Offshore Oil Corp., “Jiangsu Binhai LNG receiving station projects pre-trial approved, (Chinese), Sept. 30, 2016.

- Li, Q., “Private Enterprises’ Participation in LNG Receiving Station,” (Chinese), People.cn, Apr. 9, 2018.

- Corkhill, M., “Chinese LNG terminals hit record utilization rates,” LNG World Shipping, Mar. 8, 2018.

- Li, Y., “China’s Emerging 2nd Tier LNG Players and LNG Import Capacity Outlook,” SIA Energy: China LNG International Summit,” Mar. 16, 2016, p. 5.

- International Group of Liquefied Natural Gas Importers (GIIGNL), “The LNG Industry: GIIGNL Annual Report 2018,” 2018.

- Rogers, H.V. and Stern, J., “Challenges to JCC Pricing in Asian LNG Markets,” OIES Paper: NG 81, February 2014, p. 7.

- Li, X.M., “Shanghai trading platform will support energy market reform,” Global Times, Nov. 27, 2016.

- Lin, D. and Goh, B., “China launches commodity trading center in Shanghai, eyes Asia gas hub status,” Reuters, Nov. 26, 2016.

- Chen, A.Z. and Henning, G., “China’s Chongqing gas exchange aims to be Asia price benchmark,” Reuters, Dec. 29, 2017.

The authors

Batt Odgerel ([email protected]) is a research assistant at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) in Washington, D.C. He has also served as a research associate at the Energy Policy Research Foundation (EPRINC) and a researcher at the Institute of Strategic Studies under the National Security Council of Mongolia. He holds an MA in international economics and energy from Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, Washington, DC.

William Pack ([email protected]) is the senior policy research analyst at EPRINC in Washington D.C. He has also served as a civilian contractor for the Department of Defense, as well as a Publius Fellow at the Claremont Institute. He holds a BA in liberal arts from St. John’s College, Annapolis, Md.