New drilling reduces impacts to Greater Sage-Grouse habitat

Dave Applegate

Occidental Petroleum Corp.

Casper, Wyo.

Given that oil and gas developers are using fewer well pads to develop hydrocarbon resources in Powder River basin, and that this reduction has led to fewer roads and less habitat fragmentation, new wildlife studies are necessary in the basin to evaluate Sage-Grouse impacts from this reduction in habitat fragmentation. By reducing surface impacts, oil and gas operators in Wyoming’s Powder River basin are advancing sustainable energy development.

Recent plans in Power River basin include 3-mile lateral wells in two directions, potentially allowing recovery of hydrocarbons across 6 square miles from just one drill pad.

Background

Greater Sage-Grouse presence is generally viewed as an indicator of habitat health in the sagebrush biome. In Wyoming, nearly 70% of the state surface area covers Sage-Grouse habitat, and oil and gas extraction nearly always overlaps these areas.

Horizontal drilling, completion, and operational changes reduce both surface disturbance and fragmentation associated with the recovery of hydrocarbons. Most studies investigating impacts of oil and gas development on Sage-Grouse habitats do not include the effects of these more efficient and smaller footprint developments.

For example, historic coal bed natural gas (CBNG) development over a 4-sq mile area in Powder River basin required 32 well pads with associated access roads. Now the same size area is developed for oil-shale resources from a single drill pad with horizontal wells drilled two directions. These technological changes call for new wildlife studies which take reduced drilling footprints and reduced habitat fragmentation from access roads into account.

Sage-Grouse population decline

Greater Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) inhabit much of the western US. Hydrocarbon extraction is Wyoming’s primary economic engine, and oil and gas infrastructure nearly always overlap with Sage-Grouse habitats.

Sage-Grouse population dynamics are complex, cyclic, and likely influenced by regional climatic variation as indexed by the Pacific Decadal Oscillation.1-2 Statistically-derived population reconstruction models indicate range-wide population declines of Sage-Grouse since the 1960s.3-5

Although not listed as an endangered or threatened species, these declines have been closely observed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), as well as the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Conservation advocacy groups have filed petitions for more than 25 years to list the Greater Sage-Grouse pursuant to the Endangered Species Act.

BLM manages nearly 30% of the surface land in Wyoming and nearly 70% of the mineral resources in the state. Two examples of development restrictions to enhance Sage-Grouse survival through regulatory mechanisms include prohibiting surface-disturbing activities near Sage-Grouse breeding habitats and annual activity-timing stipulations during the breeding season. Since 2008, the State of Wyoming has taken proactive measures to limit disturbances to under 5% and habitat fragmentation to no more than one disturbance feature per square mile in the key Sage-Grouse habitats (core areas) to prevent the Sage-Grouse from being classified as a federally listed species.

Wildlife population models count male Sage-Grouse in spring at “leks” or strutting grounds to estimate changes in the abundance of Sage-Grouse. Leks are relatively small open areas in sagebrush habitats where male birds congregate each spring with a high degree of fidelity. At these communal breeding grounds, the male birds can be seen and heard dancing and displaying in the early dawn hours.

While habitat conversion from sagebrush biome to agriculture production, overharvesting, and possibly overgrazing were the primary causes for Sage-Grouse population declines before the mid-20th century, causative factors for population declines since the mid-1960s have been more diverse.6-7 Impacts during this period include areas of potential over-harvesting due to relaxation of harvest regulations from the early 1960s through the mid-1990s, landscape disturbances and fragmentation from wildfire, anthropogenic activities such as energy development, and changes in the habitat carrying-capacity due to extended drought.8-11

This analysis examines the declining fragmentation impacts from oil and gas development in Wyoming over the last 20 years (2004–2024) due to technological advances in drilling, presenting this evolution in drilling techniques as evidence that current oil and gas development within Sage-Grouse habitats is compatible with sustainable Sage-Grouse populations.

Habitat disturbance, fragmentation

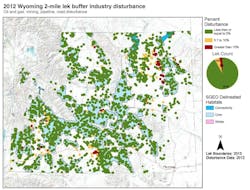

In 2015, a database created at the University of Wyoming mapped disturbances within a 2-mile buffer of individual Sage-Grouse leks. The project was primarily funded by the Petroleum Association of Wyoming (PAW). More than 2,400 individual lek maps were developed by the university’s Graphical Information Systems Center (WyGISC). Each lek map displays disturbances in a 2-mile radius around a lek.

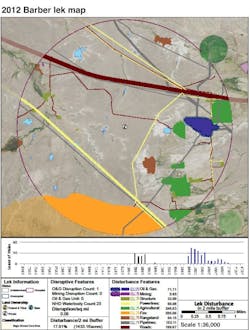

Fig. 1 shows an example lek map outside of the Wyoming core habitat for the Barber Lek. The map indicates surface disturbances by category, ongoing lek count in a bar graph, and disturbance by category within the legend. The mapping database included a 2-mile radius around each lek as both the State of Wyoming and BLM apply seasonal timing stipulations on ground-disturbing activities in this buffer. Important lifecycle nesting and brood-rearing occurs in a 12.6-sq mile area within this buffer. In this example, nearly 18% of the total lek buffer area is disturbed. Fire caused the largest percentage of the disturbance at nearly 600 acres (indicated in orange).

Lek counts started at the Barber lek after 1980 and after several consecutive annual counts, it was monitored only once in the following 15 years. The count at this lek shows significant declines from 1999 onward that were likely caused by the high disturbance level in the 2-mile buffer. The bar graph in Fig. 1 illustrates typically absent Wyoming Sage-Grouse lek-count data given the manpower needed to sample more than 2,400 known leks across Wyoming during the spring lekking season. USGS population-reconstruction models supplement these absent data.

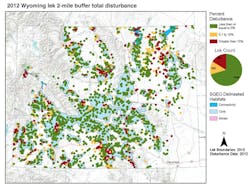

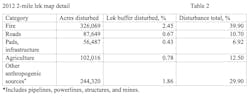

Fig. 2 summarizes individual maps where each circle represents the cumulative disturbance data in the 2-mile buffer of individual leks. Blue shading signifies Sage-Grouse core habitats. Development restrictions are much more stringent within core habitats where nearly 85% of Wyoming’s Sage-Grouse population breeds.

The green circles show that, in 2012, total surface disturbance from both anthropogenic sources (roads, agricultural production, oil and gas activities, mining, etc.) and natural causes (fire) was less than or equal to 5% of the total surface area within the 2-mile buffer for about 70% (or 1,700) of the leks in Wyoming. Having less than 5% surface disturbance near a lek is deemed acceptable for a breeding and brood-rearing habitat. This disturbance threshold guides new development in Sage-Grouse core habitats under the Wyoming Core Area Policy (WCAP).12 If a new project causes surface disturbance in the 2-mile lek buffer to exceed 5% in a core area, the developer must adjust the location of the disturbance(s) (e.g., co-locate on an existing surface disturbance) or purchase compensatory mitigation credits to advance the project. In Wyoming, these credits are currently associated with a single USFWS-approved Sage-Grouse conservation bank in central Wyoming, where Sage-Grouse habitat is protected from development.13

When this mapping was initially completed in 2012, about 322 lek buffers in Wyoming had disturbance levels between 5% and 10% (yellow circles), while 391 lek buffers had greater than 10% disturbance levels (red circles). When combined, about 30% of all leks in Wyoming had disturbance-related impacts that were expected to either reduce lek attendance or result in lek abandonment.

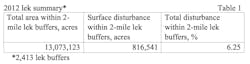

Tables 1 and 2 provide a disturbance summary for Fig. 2 which includes 2,413 Lek buffer maps. The data indicate about a 6.25% disturbance of overall Sage-Grouse habitats in Wyoming within 2-mile lek buffers, with about 40% of this overall disturbance caused by fire and 60% caused by anthropogenic sources.14

In the Great Basin (Nevada, southern Oregon, southern Idaho, and western Utah), chronic wildfire is the primary cause for past Sage-Grouse declines and will likely continue to cause significant future population declines unless targeted fire suppression, cheatgrass eradication, and habitat restoration efforts are prioritized.15

Oil and gas development provides an important subset of the disturbances in Table 1. Impacts from oil and gas development on Sage-Grouse lek attendance and population dynamics are well documented.16-19 One area of research examined the effects of well-count (pad) density on lek attendance and lek abandonment rates. Until 2012, nearly identical well count and well pad densities existed across much of Wyoming. With the advent of multi-well pads, this assumption is no longer valid.

Within the 2-mile lek buffer, well-pad density delineates scale and scope of oil and gas impacts on Sage-Grouse because each pad requires an access road which separates the landscape. Lek persistence has more than 50% probability in Powder River basin and 80% in southwest Wyoming when the 2-mile buffer contains less than 60 well pads.20 Notably, Sage-Grouse lek attendance remains unaffected for up to 12 well pads within a 2-mile radius around a lek. This finding aligns with the well-pad density criterion of one disturbance feature/sq mile for Sage-Grouse core areas outlined in WCAP.

A similar correlation for north-central Wyoming for oil and gas well density within a 0.621-mile (1 km) radius of leks indicates that densities of more than three well pads within this smaller lek buffer have a greater than 50% probability of lek abandonment.21 Combined, these impact analyses indicate that 15% (354) of identified Wyoming leks about a decade ago had been impacted by oil and gas well pad density to the extent that the probability of lek abandonment was greater than the probability of lek persistence.22

WCAP applies both disturbance (<5%) and fragmentation limitations (no more than one pad/sq mile) for new development. A subset of leks affected by oil and gas fragmentation also experience surface disturbance levels within the 2-mile lek buffer that exceed regulatory disturbance thresholds. Fig. 3, derived from completed individual lek map data, shows that oil and gas disturbances independently resulted in 194 lek buffers (8%) exceeding the 5% disturbance threshold. Of leks in Wyoming, 92% had less than 5% oil and gas disturbances within the 2-mile buffer.

Reducing surface impacts from energy development fragmentation and disturbance is imperative for achieving both Wyoming’s economic goals (ongoing oil and gas development) and conservation goals (sustainable Sage-Grouse populations).

Lek preservation with new drilling

Substantial changes in drilling, completions, and operational technologies that began 20 years ago reduce both surface disturbance and fragmentation associated with the recovery of hydrocarbons. These improvements are the result of incremental innovations in drilling rigs, development of lower friction drilling fluids, design of more robust and cable downhole tools, and ongoing learnings in completion techniques. Drilling innovations involve higher horsepower and higher torque rigs enabling high inclination and extended reach drilling. Oil and gas shale plays typically involve drilling lateral wells from 1-3 miles, often in two directions. Multiple directional or horizontal wells extend from a single pad, unlike in the past where only one vertical well was drilled per pad in this area. Using these technologies, well pads can be sited away from active lek areas.

Most studies investigating the impacts of oil and gas development on Sage-Grouse occurred before the widespread deployment of these new drilling techniques, and current oil and gas impacts are often overstated in the popular press and public agency-generated documents. The 2024 BLM resource management plan, for example, failed to analyze reduced impacts to Sage-Grouse from these drilling advances.

Impact analyses completed in the context of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) or Endangered Species Act (ESA) listing evaluations by federal agencies still refer to oil and gas lease activity, drilling permit numbers, or wildlife peer-reviewed studies situated in fields with only vertical wells. Basing impact analysis using these metrics and outdated studies are no longer the best available science in evaluating the impacts of oil and gas development on Sage-Grouse.

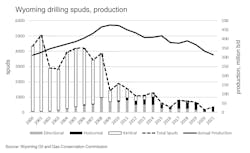

Fig. 4 shows spudding in Wyoming by well type and count from 2000 through 2021, highlighting the increase in horizontal drilling and decline of vertical wells. More than 4,000 vertical wells spudded in Wyoming in 2000. Of 1,076 wells spudded in 2012, 339 were vertical, 244 were horizontal, and 493 were directional. In comparison, an average of 300 horizontal wells (and about 550 total wells on average) spudded per year during the 5-year period from 2017 through 2021.

Total 2004-24 production in Wyoming peaked in 2009 at about 450 MMboe. Current total production from about 550 well-spuds per year using the new drilling techniques, nearly matches total production in the early 2000s, when more than 4,000 vertical wells were drilled a year (due to the well-count intensive coal-bed methane play in northeast Wyoming).

Improved Powder River basin habitats

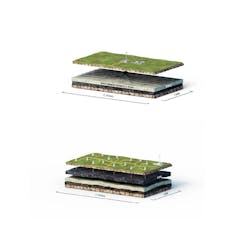

Fig. 5 compares disturbance footprints of vertical and horizontal wells. Innovative drilling and completion technologies reduce habitat fragmentation, which can be measured by different variables such as habitat patches or length of habitat edges (e.g., road lengths within the habitat). In this comparison, fragmentation levels are independent of habitat loss.23 Each of these development profiles have similar disturbance levels (<1%) per section developed, but different levels of habitat fragmentation.

This example compares energy produced/acre disturbed and the energy produced/pad feature from Powder River basin CBNG in the late 1990s with a 2023 horizontal multi-well pad targeting deeper shale oil in the same producing basin.

The CBNG play deployed eight vertical wells/section, each requiring an access road. The horizontal play, however, concentrates total pad disturbance at two nearby locations. The fragmentation profile is significantly lower in the horizontal play, with truck traffic going to two co-located pads (drill pad and equipment pad) serving four sections versus 32 pad locations in the CBNG play.

The energy produced per acre disturbed increased by a factor of 2.8 in Powder River basin, from 5 Gw-hr to 14 Gw-hr, while the energy produced per surface feature increased by a factor of more than 40, from 4 Gw-hr to 167 Gw-hr (Box 1). The historic CBNG development divided the four sections developed into more than a dozen habitat patches, while current development creates as few as two habitat patches in the four sections of development, illustrating the significant reduction in habitat fragmentation associated with drilling and developing long-lateral horizontal wells from a limited number of pads.

References

- Row, J.R. and Fedy, B.C., “Spatial and temporal variation in the range-wide cyclic dynamics of greater Sage-Grouse,” Oecologia, Vol. 185, No. 4, Oct. 19, 2017.

- Ramey, R.R., Thorley, J.L., and Ivey, A.S., “Local and population-level response of Greater Sage-Grouse to oil and gas development and climatic variation in Wyoming,” PeerJ, 6:e5417, Aug. 14, 2018.

- Garton, E.O., Connelly, J.W., Horne, J.S., Hagen, C.A., Moser, A., and Schroeder, M.A., “Greater Sage-Grouse population dynamics and probability of persistence,” in Greater Sage-Grouse, Ecology, and Conservation of a Landscape Species and Its Habitats, Studies in Avian Biology, S.T. Knick and J.W. Connelly, editors, University of California Press, Berkley, Calif., Vol. 38, 2011, pp. 293-382.

- Garton, E.O., Wells, A.G., Baumgardt, J.A., and Connelly, J.W., “Greater Sage-Grouse Population Dynamics and Probability of Persistence,” Final report to Pew Charitable Trusts, Mar. 15, 2015.

- Coates, P.S., Prochazka, B.G., Aldridge, C.L., O'Donnell, M.S., Edmunds, D.R., Monroe, A.P., Hanser, S.E., Wiechman, L.A., and Chenaille, M.P. “Range-wide population trend analysis for Greater Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus)—Updated 1960–2022,” US Geological Survey Data Report 1175, 2023, pp. 1-17.

- Knick, S.T. and Connelly, J.W., “Greater Sage‐Grouse and Sagebrush: An Introduction to the Landscape,” in Greater Sage‐Grouse: Ecology and Conservation of a Landscape Species and Its Habitat, Studies in Avian Biology, S.T. Knick and J.W. Connelly, editors, University of California Press, Berkley, Calif., Vol. 38, 2011, pp. 1-9.

- Patterson, R.L., “The Sage Grouse in Wyoming,” Sage Books, Denver, Colo., 1952.

- Dinkins J.B., Duchardt, C.J., Henning, J.D., and Beck, J.L., “Changes in hunting season regulations (1870s-2019) reduce harvest exposure on greater and Gunnison Sage-Grouse,” Plos One, Vol. 16, No. 10, Oct. 5, 2021.

- Baker, W.L., “Pre-European-American and Recent Fire in Sagebrush Ecosystems,” in Greater Sage-Grouse, Ecology and Conservation of a Landscape Species and Its Habitats, Studies in Avian Biology, S.T. Knick and J.W. Connelly, editors, University of California Press, Berkley, Calif., Vol. 38, 2011, pp. 185-201.

- Naugle D.E., Doherty. K.E., Walker, B.L., Holleran, M.J., and Copeland, H.E., “Energy Development and Greater Sage-Grouse,” in Greater Sage-Grouse, Ecology and Conservation of a Landscape Species and Its Habitats, Studies in Avian Biology, S.T. Knick and J.W. Connelly, editors, University of California Press, Berkley, Calif., Vol. 38, 2011, pp. 489-502.

- Coates, P.S., Prochazka, B.G., O’Donnell, M.S., Aldridge, C.L., Edmunds, D.R., Monroe, A.P., Ricca, M.A., Wann, G.T., Hanser, S.E., Wiechman, L.A., and Chenaille, M.P., “Range-wide Greater Sage-Grouse hierarchical monitoring framework—Implications for defining population boundaries, trend estimation, and a targeted annual warning system,” US Geological Survey Open-File Report 2020–1154, 2020.

- Greater Sage-Grouse Core Area Protection Executive Order, Order 2019-3 (Replaces 2015-4 and 2017-2), State of Wyoming, 2019.

- Pathfinder Ranches, Sage-Grouse Credits, www.pathfinderranches.com, 2024.

- Graf, N., “Wyoming Lek Mapping Update,” University of Wyoming Geographic Information Science Center, Aug. 16, 2016.

- Coates, P.S., Ricca, M.A., Prochazka, B.G., Brooks, M.L., Doherty, K.E., Kroger, T., Blomberg, E.J., Hagen, C.A., and Casazza, M.L., “Wildfire, climate, and invasive grass interactions negatively impact an indicator species by reshaping sagebrush ecosystems,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 113, No. 45, Nov. 8, 2016, pp. 12745-12750, corrected Nov. 9, 2016.

- Holloran M.J., Kaiser, R.C., and Hubert, W.A., “Yearling Greater Sage-Grouse response to energy development in Wyoming,” Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 74, Vol. 1, Jan. 1, 2010, pp. 65–72.

- Walker, B.L., Naugle, D.E., and Doherty K.E., “Greater Sage-Grouse Population Response to Energy Development and Habitat Loss,” Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 71, No. 8, November, 2007, pp. 2644–2654.

- Taylor, R.L., Tack, J.D., Naugle, D.E., and Mills L.S., “Combined effects of energy development and disease on greater Sage-Grouse,” Plos One, Vol. 8, No. 8, 2013.

- Green, A.W., Aldridge, C.L., and O’Donnell, M.S., “Investigating Impacts of Oil and Gas Development on Greater Sage-Grouse,” The Journal of Wildlife Management, Oct. 18, 2016.

- Doherty, K.E., Naugle, D.E., and Evans, J.S., “A currency for offsetting energy development impacts: horse-trading Sage-Grouse on the open market,” Plos One Vol. 5. No. 4, Apr. 28, 2010.

- Hess, J. and Beck, J., “Disturbance factors influencing greater Sage-Grouse lek abandonment in north-central Wyoming, “Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 76, Vol. 8, July 30, 2012, pp.1625–1634.

- Applegate, D. and Owens, N., “Oil and gas impacts on Wyoming’s Sage-Grouse: summarizing the past and predicting the foreseeable future,” Human-Wildlife Interactions, Vol. 8, No. 2, October, 2014, pp. 284-290.

- Fahrig, L., “Ecological Responses to Habitat Fragmentation Per Se,” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, Vol. 48, May 13, 2017, pp. 1-23.

Author

David Applegate, PE ([email protected]), is a public lands policy manager for Occidental Petroleum Corp. in Casper, Wyo. He holds a BS in civil engineering from the University of Wyoming and an MS in environmental engineering from Duke University, Durham, NC. He is a member of the American Society of Civil Engineers.