P. 2 ~ Continued - Trends emerge on hydraulic fracturing litigation

Displaying 2/6

View Article as Single page

Second, the study may encourage or discourage lawmakers from bringing hydraulic fracturing within the scope of the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act.

Finally, much of the threat of water contamination predominantly arises when the energy company allegedly is deficient in casing the well. As the draft study itself mentions, proper well design and construction can play a major role in preventing contamination. As such, it is quite possible that EPA will conclude that mandates and design regulations are needed to ensure well integrity. Further, the industry has recognized the importance of educating the public about the effect of well design and geology in preventing potential consequences on aquifers, as is evident from television commercials on the subject.

While the imposition of these regulations would come with additional regulatory costs of compliance, at this point, there does not appear to be anything on the horizon that could fundamentally jeopardize the continued expansion of shale gas development.

Perhaps the most likely scenario is that the EPA study will affirm the conclusions of other recent studies, which conclude that hydraulic fracturing does not pollute groundwater, nor does it pose a disproportionate threat to public health and safety when compared to other resource extracting operations.

For instance, a study commissioned by the British Parliament recently determined, in authorizing the use of hydraulic fracturing in the UK, that there was no evidence that fracturing posed a direct risk to underground water aquifers provided that the drilling well was constructed properly.2

A recently released Duke University analysis of 68 private groundwater wells across Pennsylvania found that, while those wells near fracturing sites did have increased concentrations of methane, they were not contaminated with drilling toxins. Though based on a limited sample size, the study found no evidence of contamination from the chemicals used in the fracturing, which are often the focus of litigation and public health fears.3

On May 2, 2011, the University of Texas announced a $300,000, 9-month study to explore further the validity of continuing allegations that fracturing can contaminate or pollute groundwater. Based on what has gone before, including years of experience with well-fracturing technology designed to stimulate production of hydrocarbons, a report different from previous findings would appear unlikely.4

The most significant threat then, from a regulatory perspective, is not disclosure or well-design mandates or the conclusions of the EPA study, but rather the potential for delays in granting permits by state agencies paralyzed by political pressure. Furthermore, with the exception of an outlier Arkansas case that alleges that hydraulic fracturing causes earthquakes, development of tort law associated with fracturing operations also does not at the moment appear to present a substantial threat to the industry.

While it is true that a couple of cases have settled for reasonable sums, so far it would appear that the majority of pending cases does not contend that fracturing itself invariably pollutes the local air and water, but rather alleges that the particular practices of the operations in question were poorly managed. Therefore, case law developed from such operations may come to resemble case law applicable to other oil and gas exploration and production operations, as well as general tort law associated with operations of many other industries, where companies are sued for negligent operations, but the majority of the industry is able to continue on, largely unhindered.

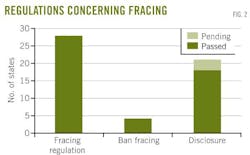

Fig. 2 shows the number of pending and passed regulations concerning hydraulic fracturing.

Displaying 2/6

View Article as Single page