Mexico's deepwater exploration

Undisclosed challenges to be faced

DANIEL ARANDA, GARDERE WYNNE SEWELL, MEXICO CITY

THE MEXICAN GOVERNMENT through the National Hydrocarbon Commission (NHC) released the fourth bidding round for deep-water on December 17, 2015. As expected, the NHC opted for a license contract as opposed to the production sharing schemes used in Round 1.1 and 1.2. In this round, the NHC is putting to bid 10 contract areas (see Figure 1) distributed within the Perdido Fold Belt (four areas) and Salina's Basin (Cuenca Salina) (six areas), both, deep-water regions in the Gulf of Mexico.

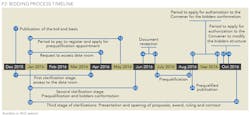

The bidding guidelines as well as the model license templates are available for review on the NHC's website (http://ronda1.gob.mx/). The bidding process timeline is summarized in Figure 2.

So far, 20 companies have expressed interest in participating in Round 1.4., with the following 13 already requesting and paying for access to the data room (as of press time, 10 have started the prequalification process):

- Atlantic Rim México, S. de R.L. de C.V.

- Shell Exploración y Extracción de México, S.A. de C.V.

- Total E&P México, S.A. de C.V.

- Chevron Energía de México, S. de R.L. de C.V.

- ExxonMobil Exploración y Producción México, S. de R.L. de C.V.

- Cobalt Energía de México, S de R.L. de C.V.

- Hess México Oil and Gas, S. de R.L. de C.V.

- NBL México, Inc.

- Statoil E&P México, S.A. de C.V.

- BP Exploration México, S.A. de C.V.

- BHP Billiton Petróleo Operaciones de México, S. de R.L. de C.V.

- Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation

- Petro-Canada (International) Holdings B.V.

Though the bidding guidelines have been streamlined based on the experience of Round 1.3, and that the Mexican government effectively adopted a contract model that adjusts to international practices, there are certain aspects that are not fully disclosed or addressed that bidders should consider when structuring their proposals and assessing their risk exposure.

In that regard, this article intends to encapsulate those additional aspects that may not qualify as no-so-obvious intrinsic challenges:

Environmental risks

Prior to the energy reform, the Mexican Congress enacted a new Environmental Liability Law which enabled condemnation to punitive and consequential (indirect) damages for the first time in Mexico. Hence, even though the model contract effectively assesses the responsibility for ensuring environmental safety to the contractor, what is not spelled-out in the contract is that contractors will become liable not only before the NHC, but also before the populations that could be affected by an environmental accident, as well as non-governmental organizations; and federal and local Environmental Protection Agencies (EPAs) The preceding without limiting other potential administrative, civil or criminal remedies.

To this extent, both the initial transition period, as well as the relinquishment of the awarded areas become of the utmost importance, since the contractor will assume any and all environmental liabilities that are not disclosed to the NHC.

Availability of marine equipment and specialized workforce

It would be unthinkable to discuss deepwater exploration without considering the need of specialized vessels. In March 2015 the Mexican government issued Maritime Regulations that enable the authorities to allow foreign flag vessels of highly specialized nature to perform internal water navigation. Although this enables the vast majority of vessels required for deepwater exploration (with an exclusion of tugboats, and supply and fast-transportation vessels) to obtain a navigation permit, it still requires the cooperation of a Mexican Shipping Company, which as of today can only be held in 49% by foreign investment. These requirements should be considered when computing costs since they necessarily imply an alliance/service contract with a Mexican investor.

Likewise, deep-water exploration will require the employment of a highly specialized workforce on a worldwide low-offer environment. In addition, both the Mexican Federal Labor Law and Immigration Law continues to impose a 10% cap on the number of foreign employees that can be employed by a Mexican company. In order to surpass these caps companies have utilized other mechanisms such as the use of outsourcing companies. However, since 2012, these arrangements have been subjected to additional governmental scrutiny, which could render them an ineffective labor liability shield for contractors.

Civil liability

As in the case of environmental liability, recent court decisions stand in clear opposition to more than 65 years of consistent legal precedents, with the imposition of punitive damages being used to dissuade others from committing such conducts. However, such damages are often assessed at the entire discretion of a judge who may not yet have faced the question of what should be considered dissuasive in this situation. The issue of class actions has also recently been introduced to the legal framework, being that as a result of that introduction, a claim has already been brought (though not yet accepted) against BP related to the Deepwater Horizon spill.

As of 2013, the courts have issued more than 13 isolated legal precedents that set aside Mexican legal traditions upholding the validity of the corporate veil. As a result, even though Mexican legal tradition has upheld that the liability of the shareholders/members of a company was limited to their economic contributions, as of now, contractors should also compute in their risk matrix the possibility of a Mexican judge piercing the corporate veil to impose personal liability to its shareholders/members if a claim is brought against them by a third party different from the NHC.

Vicinity of contractual areas

Though the contract model includes a clause that addresses the possibility of requesting unitization of related contractual areas, it is unclear as to whether the unitization contract will void or supersede the provisions of the license agreement. Moreover, when looking at the location of the first contractual area, it should be evident whether the model contract fails to include perhaps one of the major challenges not addressed in the RFP-the existence of a transboundary reservoir. In case of such a reservoir, by law Pemex would become a partner of the contractor for at least 20% of the required investment. This unforeseen circumstance could ultimately affect the financial matrix of a contractor when booking reserves.

Thus, while assessing a company's participation into Round 1.4, contractors should carefully consider the foregoing among the potential risks in order to prevent any unpleasant irrevocable surprises.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Daniel Aranda is a partner at Gardere Wynne Sewell LLP and is the leader of Gardere's Energy and Government Procurement Practice in Mexico City. The bilingual, bicultural corporate lawyer serves international energy, pipeline, banking and finance sector clients in the United States and Mexico.