Oil and gas security

Standardization and continuity in security risk assessments improve decision-making

Paul Mercer, Hawk Sight Security Risk Management Ltd., London

For international oil companies operating in hostile environments, corporate security can be a confusing and costly function, and one that is often outsourced to specialized consultancies at significant cost. The trouble is, ask three different security consultants to carry out the same Security Risk Assessment (SRA) and you may well get three different answers.

This lack of standardization and continuity in SRA methodology creates confusion between those charged with managing security risk and those who sign off on the budget. So how can security professionals effectively translate the traditional language of corporate security in a way that aids both understanding and also the efficient and cost-effective development of corporate security systems appropriate for their intended use?

Standardized security risk methodology is a three-stage process:

- Develop a working understanding of what is most important to the operation under review.

- Gain an in-depth understanding of the security threat environment in which it operates.

- Assess how vulnerable critical elements of the project are to the threats identified.

Through this process, security professionals can develop a system that is appropriate for its intended use and flexible enough to be adapted to an ever-changing security environment. They also can directly compare projects in different environments so they can benefit from lessons learned globally.

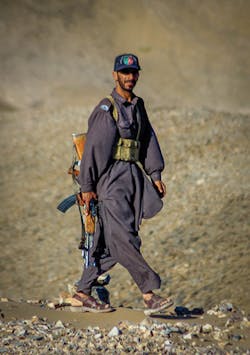

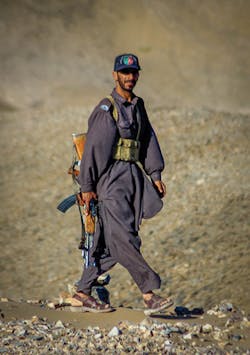

Photos by Hawk Sight Security Risk Management Ltd.

Furthermore, by ensuring the methodology used is compliant with enterprise risk management standards, we can begin to translate the traditional language of security into that of enterprise risk. This promotes understanding across all business functions and changes the perception of corporate security from a simple cost center to one that adds value.

CHANGING THE APPROACH

To benefit from such an approach, some fundamental changes need to be made.

First, the security risk analyst needs to gain an in-depth understanding of the operation or project being considered in order to prioritize what supporting assets need protecting the most. These may be people, physical assets, technology or information itself.

Next we must understand security threats originating from a human source such as military conflict, crime and terrorism, and those emanating from a non-human source such as natural disasters and epidemics.

Most high-profile security threats to international oil and gas operations are derived from a human source. Louise Richardson, renowned political scientist and author of "What Terrorists Want" says "terrorists seek revenge for injustices or humiliations suffered by their community." To effectively assess the security threat people bring to your project, both now and in the future, we must consider not only the action or activity carried out, but also who carried it out and why.

A security threat assessment must therefore identify:

Threat activity: Kidnap for Ransom of your company's employees, for example.

Threat actor: Who might carry out such activity?

Threat driver: What motivates the threat actor (perceived lack of employment opportunity, revenge for the actions of a contracted corporate security team, etc.)?

Intent: How often has the threat actor carried out the threat activity or have they only threatened to do so?

Capability: What competency do they have now and in the future?

Security threats emanating from non-human sources such as natural disasters, communicable diseases and accidents can be assessed in a similar assessment process. For example:

Threat activity: Virus outbreak causing serious illness or death to company employees.

Threat actor: What might be responsible? Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

Threat driver: How might this spread? Through close contact with an affected individual.

What Potential does the threat actor have to do harm? Up to 300 people may have died of MERS in Saudi Arabia.

What Capacity does the threat have to do harm? MERS has been reported in over 19 countries.

But a security threat by its very nature, be it human or non-human, is not static and must be continually monitored. As a result, an annual SRA, as many companies prescribe, may still leave your operations exposed.

To effectively monitor security threats, we must consider events that might escalate them to a higher level, but also what events may de-escalate them. For example, security forces firing on a protest march may escalate the potential of a violent response from that group, while effective communication with protest leaders may, in the short term at least, de-escalate the potential of a violent exchange. This type of analysis can help with effective threat forecasting.

The key challenge facing corporate security professionals is, however, "selling" their security threat analysis to the oil and gas company. The perception of security threats may differ from person to person due to an individual's experience, background or personal risk appetite.

To effectively sell a threat analysis, assessment must be put into context by creating credible scenarios specific to the operation or project in question. There is little point specifying terrorism as a principle risk because it is too broad a threat. But outlining the risk of an armed attack by local militia due to an ongoing dispute on employment opportunities allows us to make the threat more plausible and to assess if existing control measures might withstand the incident.

ASSESSING VULNERABILITY

Assessing the effectiveness of existing control measures forms a key part of the Vulnerability Assessment.

When assessing vulnerability, security professionals must:

- Consider how attractive the assets might be to threat actors and how easily they can be identified and accessed.

- Assess how well these assets are already protected against this threat activity.

- Consider how well equipped an organization is respond to an incident, should it occur despite control measures.

Like a threat assessment, this vulnerability assessment needs to be ongoing to ensure controls not only function correctly now, but also are still relevant to the ever-changing security environment in which the project operates.

The Statoil "The In Anemas Attack" report, which followed the January 2013 attack in Algeria, made recommendations for the "development of a security risk management system that is dynamic, fit for purpose and geared toward action. A standardized, open and well-defined security risk management methodology will allow both experts and management to have a common understanding of risk, threats and scenarios and evaluations of these."

But maintaining this essential process is no small task and requires specific skillsets and experience. According to the same report, "…in most cases security is part of broader health, safety and environment positions and one for which few people in those roles have particular experience and expertise. As a consequence Statoil overall has insufficient full-time specialist resources dedicated to security."

Anchoring corporate security in effective and ongoing security risk analysis not only facilitates timely and effective decision making but also introduces a broader quiver of security controls that may not have been considered as a part of the corporate security system before.

AN INCLUSIVE AND CEREBRAL APPROACH

Before jumping into a one size fits all, military approach to security system design -one which depends on the standard, costly combination of physical security, technology and armed security personnel-let us blow the dust off the SRA and consider how else we might begin to mitigate the security risks we have identified.

Today, international oil companies engage social scientists to carry out Social Impact Awareness (SIA) studies to inform Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs. But how often is such activity considered a part of corporate security? An SIA study may identify, for example, the key subsistence activity of the locals in a particular Area of Operation (AOO) such as farming, which relies on minimizing the environmental impact of an operation. Furthermore, it may identify concerns such as grievances around lack of education opportunities and healthcare. By minimizing the impact on farming and providing schools and healthcare to the local community, you have effectively suppressed a common threat driver to operating in developing countries, mitigating a potential risk before spending a penny on traditional security measures.

Table 1 draws on information from the UNDP Human Security Index (HDI). It shows a correlation between the Global Peace Index (GPI), a leading measure of national peacefulness from the Institute of Economics and Peace, with indices quantifying some key security threat drivers that can be managed through effective corporate social responsibility programs.

A clear correlation can be seen between the level of national peace and the level of wages, education, health, and food. These are all services that can be, and in many cases, are included as part of a CSR program and can have a direct impact on security at the operational/project level. Taking this more inclusive corporate security approach at the security planning stage (and gathering feedback about its effectiveness) means you can reassess security threats at a tactical and human level and engage with specialists throughout the organization. This increases your understanding and veracity of the corporate security function.

For example, I was once asked to use the SRA approach to justify a considerable increase in the number of armed troops required to protect a pipeline in Kurdistan, together with the installation of over 50 kilometers of fencing and surveillance. The threat assessment identified two significant risks, one from a targeted suicide bomber attack and the other from collateral exposure to an air attack against militia known to operate near the pipeline.

By mapping threats against critical assets, it was agreed no number of armed guards would reduce the likelihood of the pipeline rupturing due to an airstrike. Even the suicide bomber threat would require fencing at significant standoff, as it is not feasible to identify, capture, and disarm a potential suicide bomber before detonation.

So we moved our attention from preventing the threat activity to responding to it. By adopting a procedural update to response planning we demonstrated we could lower the risk to a level considered "As Low as Reasonably Practicable" at a fraction of the cost of the physical, technical and manpower controls that were initially recommended.

Traditional physical, manpower and technological security remains an essential aspect of operational security, but one that should perhaps not be considered as the first step in security system design. Rather, it should be the final step that fills in gaps that cannot be mitigated through softer security considerations.

Not only can a more inclusive and cerebral approach to security save you money, but it can also lower the overall project risk profile. Military inspired security systems focus on military models employing uniformed armed security, centrally trained and entirely under the command of officers and NCOs.

Contracted armed security, on the other hand, draws on private security companies that are, in most cases, not under the direct control of the corporate entity paying for them and who come from a variety of different backgrounds. The posture of contracted armed security personal will reflect directly on your company and, may actually increase your company's target attractiveness. Many corporate entities have signed on to the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, which outlines the huge responsibility of corporate entities when contracting private armed security services.

For international oil companies operating in hostile environments, in-depth, ongoing Security Risk Analysis can facilitate an understanding of the corporate security function and offer ongoing analysis for effective decision-making. Rather than a military inspired model that may neither be suitable nor entirely under your control, the more inclusive approach described above can limit the likelihood of an attack and create cost savings, while also ensuring there is an appropriate response.

About the author

Paul Mercer is director of Hawk Sight Security Risk Management Ltd., designer of the Hawk Sight Security Risk Management solution, and an expert with the Hostile Environment Liability Protection program. He is a former Royal Naval Officer who has worked as a security risk consultant the past 12 years while living and working throughout the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. Contact him at [email protected].