Are the fiscal regimes of West Africa deepwater attractive to foreign investors?

Ighodalo Itama Aimienwanu University of Dundee Dundee, Scotland

EDITOR’S NOTE: This in-depth article is extracted from an academic paper written by Ighodalo Aimienwanu, who recently completed work on his MBA degree in oil and gas management at the Centre for Energy, Petroleum and Mineral Law and Policy at the University of Dundee in Scotland. For the sake of brevity, we have deleted his footnotes and bibliography. The article examines the financial risks and benefits of petroleum exploration in West African deepwater.

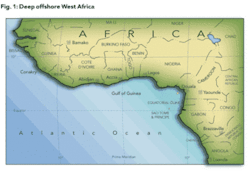

The world’s major deep offshore regions, the Gulf of Guinea (West Africa), Gulf of Mexico (GoM), and Brazil, have witnessed a flurry of exploration and development activities in recent years. Rising oil demand, declining shallow water and onshore reserves, political instability in big onshore areas, significant deepwater discoveries, and high oil prices have fuelled these deepwater activities.

However, deepwater exploration requires sophisticated technology and huge capital expenditures. Likewise, the investment risks are considerably higher than with traditional onshore exploration activity, accounting for the relatively fewer players. In evaluating the business decision to invest in a country, investors typically consider macroeconomic and political factors, geology and the fiscal terms, making it imperative for governments to design unique fiscal systems to attract investments.

Deep offshore West Africa is unique because of the high exploration success rates, favorable geology, crude quality, proximity to key markets, and relative political stability, in recent times, in most of the countries in the region. The region is considered the utmost prize in Africa. It is currently in the limelight as a result of stunning discoveries in Equatorial Guinea, Angola, and Nigeria.

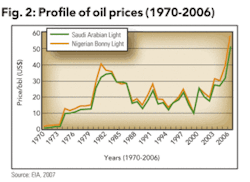

Although current high oil prices make the economics of exploration and development in most regions favorable, the true test of a fiscal regime is its long-term flexibility to (historically) volatile oil prices (see Fig. 2) and fluctuating costs which could adversely impact investment outcome.

This article evaluates the attractiveness of the fiscal regimes of the deepwater areas of Nigeria, Angola and Equatorial Guinea, being the three most important countries in the Gulf of Guinea deep offshore area based on the level of discoveries and production output. It begins by discussing the evaluation criteria namely; government-take, stability, cost recovery, and re-investment incentives. This is followed by a discussion of the legal frameworks for their fiscal regimes and an analysis of their attractiveness using the evaluation criteria above. It also looks at their global competitiveness and concludes with their attractiveness.

Fiscal regimes evaluation criteria

Fiscal terms depend on other factors such as geology, oil quality, transportation costs, as well as the political and macroeconomic environment of the countries. Consequently, while the criteria discussed below are crucial in determining the attractiveness of fiscal regimes, because they can be approximated in quantitative terms, they are by no means exhaustive.

Typically, two broad interest groups must be satisfied for a fiscal regime to be attractive in the long and short term — the investors (oil companies) and host government. The government perceives itself as the custodian of its citizens’ collective wealth, while oil companies must make appropriate returns on investment for their shareholders. If any of these parties’ interests is not sufficiently guaranteed by the regime, investment in petroleum exploitation may not take place, or if it does, may not be sustainable in the long term or may be done inefficiently.

The evaluation criteria are an attempt to achieve a delicate balance between these two seemingly conflicting objectives, but which could be jointly fulfilled by an appropriately structured fiscal regime.

Government take

Government-take refers to the share of profits accruing to government (expressed as a percentage) from the exploitation of a state resource by an investor, and includes royalties, income taxes, bonuses, profit oil, and fees. It does not take into account other aspects of the fiscal regime such as ring fencing re-investment credits, domestic market obligations, cost recovery limits, etc.

Government-take should be directed at the economic rent, i.e. ensure neutrality, because this ensures that the investor recoups costs and achieves the minimum required return on investment. It also guarantees government revenues when a positive NPV is achieved, without affecting the investment decision i.e. it would neither encourage over-investment nor under-investment. Such a system is regarded as progressive.

While this appears fairly straightforward in theory, it is difficult to determine the economic rent in practice, because several variables influence the available economic rent. Consequently, what constitutes a fair government-take differs across geographical locations, political jurisdictions, different oil prices, and field sizes and types (within the same country).

Government-take tends to be lower for deepwater areas compared to similar projects in other areas (see Appendix I). The size of the take affects field profitability and viability from the investor’s view point, as is the timing of government’s take (irrespective of the size). A predominantly front-end loaded regime is regarded as regressive and would discourage investment, because it adversely impacts field economics and transfers most of the project risk to the contractor.

Conversely, a predominantly backend loaded government-take, pushes most of the risk to government, leaving government with little or no guaranteed earning. It may be argued that governments should be relatively more patient than investors, but political exigencies and other development needs combine to motivate governments’ (particularly in developing countries) desire for steady early revenue streams. Thus, a balance between the two extremes may be ideal.

Governments may enhance the available take by reducing the level of perceived political risks associated with investing in the country, which in turn reduces the minimum required return by the investor.

Stability

Long-term planning is inevitable in the petroleum and mineral mining sector, and stability provides this platform. Oil exploration and production take place over a long period, but project appraisal is based on (negotiated or stipulated) fiscal terms prior to project commencement. During project execution, several variables beyond the host government’s control such as oil price, exploration and development costs, etc. may change, but investors would not want variables within government’s control such as policies and other political variables to change.

Stability of a fiscal regime implies that it will remain unchanged, making profit or cash flow projections based on its terms realistic. Fiscal regime stability deals with insulating a project from the effects of variables within and outside government control, i.e. stable government policy and flexibility of the regime.

In order to assure stable government policies over the life of projects, investors insist on the insertion of stabilization clauses to ensure government’s commitment to the negotiated fiscal terms even when there is a change in government personnel. The efficacy of these clauses in dissuading policy changes is doubtful, since governments may vary policies to satisfy national and political interests. A more viable option is adopting clauses that permit periodic re-evaluation (after prior industry consultations) and incorporate provisions for compensation where losses result.

Secondly, flexibility suggests that neither government’s nor investor’s return is eroded by changes in: oil price; project costs; and available economic rent, since any considerable changes in either party’s return would instigate clamor for renegotiation. Since these changes sometimes inevitable, the fiscal system should assure easy adaptability when they occur. A regime directed at profits or positive NPV would achieve this, the latter being more flexible.

Cost recovery and re-investment incentives

The timing of cost recovery, magnitude of recoverable cost items and possibility of escalating cost recovery through re-investment incentives are crucial to a fiscal system’s attractiveness, as they impinge on the project’s NPV and the profitability of further investments.

Very restrictive cost recovery systems increase an investor’s business risks. Conversely, very liberal terms transfer business risks to the government, a situation governments are averse to. Considering the high risk of failure associated with oil exploration, equity demands that an investor should be guaranteed recovery of project costs in order to preserve shareholder value and repay providers of capital.

Allowances like ring fences, re-investment credits (e.g. as a percentage of exploration expenditure) and uplifts provide for escalation of cost recovery from repeated investment. These provisions result in higher returns for multiple as against stand-alone projects, by increasing the project revenue. They are referred to as tax allowances or credits, but are cost related. Investors prefer repeated investments in a known terrain, for reasons such as familiarity with the geology, existing relationships and considerations.

Thus, a tax regime that allows early cost recovery of project costs and provides incentives for reinvestments will attract investment, encourage re-investment and boost revenues to government and the investor.

The deepwater fiscal regimes of Angola, Nigeria, and Equitorial Guinea

Having discussed the evaluation criteria, this section reviews the legal framework for deepwater exploitation in the three countries (details are presented in Appendix II).

Angola

Petroleum activities in Angola are governed by the Petroleum Law of 2004, which is in many respects similar to the 1978 legislation (OECD/IEA, 2006). The law confers ownership of petroleum resources on the state and makes the state-owned oil company, Sonangol, the sole holder of petroleum rights. Thus, companies can only perform petroleum exploration and production activities in association with Sonangol. This partnership could take the form of a registered company, a joint venture, or production sharing contract. Sonangol may hold equity in a field via its subsidiary, Sonangol P & P, through which it has participated in some development blocks and therefore, has multiple roles.

Sonangol represents government’s interest in negotiating petroleum exploration and production agreements with the international oil companies, which are typically in the form of concession agreements or production sharing contracts (PSCs). The PSCs cover deepwater acreage and are typically negotiated on an individual basis.

Nigeria

The Nigerian offshore deepwater exploration and production agreements are governed by the Deep Offshore and Inland basin Production Sharing Act of 1999 (Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 1999). The law defines deep offshore as any water depth beyond 200 meters and brings all other relevant petroleum tax legislation in conformity with its provisions.

The law provides for more favorable fiscal terms than what obtained for onshore areas. It contains provisions for royalty rates on a sliding scale and an oil prospecting license up to a maximum of ten years. The enactment of this law was premised on the persistent problems experienced by government in funding its joint venture cash call, lack of an enabling legislative backbone for deep offshore petroleum exploitation and the impact it was having on the development of exploration acreage.

Equatorial Guinea

Petroleum activities in Equatorial Guinea are governed by the Hydrocarbons Law number 8 of 2006 (Hydrocarbons Law, 2006; Mobbs, 2007). It gives petroleum exploitation rights to the state and stipulates that petroleum exploration and production agreements between government and foreign oil companies shall be based on the Model PSCs. All prior PSCs are to be renegotiated in line with the terms of the new law, which replaces the 1981 law and its amendments. Additionally, the new law contains domestic market obligations.

The country’s petroleum resources are largely offshore. In 2001, it established a national oil company, GE Petrol, to manage government’s interest in the PSCs with foreign oil companies, but may also go solo in unlicensed acreage. Its primary role is commercial, with responsibility for promoting the country’s exploration acreage, but may also seek exploration acreage abroad (Hydrocarbons Law, 2006; KPMG, 2006).

Comparative analysis of the attractiveness of the deepwater fiscal regimes

Having set out the criteria for evaluation and the legal framework (for highlights of the three fiscal regimes see Appendix II), a comparison will now be made between the regimes on one hand and those of other deep offshore areas, bearing in mind differences in geology, oil quality, drilling success rates, economic and political development.

Broadly speaking, the West Africa deep offshore region has several advantages: high drilling success rates of about 60%, compared to 28% for the Gulf of Mexico; relatively higher oil quality, combining a higher API gravity (compared to Latin America) and low sulphur content; low transportation costs and relatively easy transport access to key markets; and lower exploration and production costs compared to GoM.

Government take

What may be considered a fair government take varies widely from 45 to 85%, depending on the investor’s political and business risks in exploration and production. For example, while Ivory Coast, with a higher risk profile has an average government-take of 49%, Cameroon with a relatively low risk profile has an average of 74 to 78%.

Comparing government-takes in the deep offshore “Golden Triangle,” the US GoM and Brazil have average government-takes of 38 to 42% and 60 to 65%, compared to Nigeria’s 64 to 70%, Angola’s 60 to 85%, and Equatorial Guinea’s 39-75%. While government take in Angola and Nigeria appear relatively higher, the very favorable geology and stable terrain may support this level.

Angola’s reliance on large front-end bonuses may reflect its considerable exposure to oil-backed short-term external debt, illustrating the relationship between a country’s macro-economic conditions and the design of its fiscal regime. That nation’s bonuses are the highest in the world, and government receives all revenues above $32/barrel, but the regime is regarded as one of the most progressive in the world, because the absence of royalties and use of a ROR sliding scale ensures its relative neutrality.

Also, given that the bidding process is competitive, the signature bonus size may approximate investors’ evaluation of the acreage’s prospectivity. Overall, the regime is considered attractive.

Key features of Nigeria’s PSC include a sliding scale royalty system depending on water depths, profit-oil split based on level of production, a 50% tax allowance, and moderate bonuses. It relates the level of front-end receipts to the difficulty of exploration and development, and back-end profit sharing to production output. When viewed against other advantages earlier discussed, the take may be justified.

Equatorial Guinea differs from the previous two with a very competitive lower limit, but a high upper limit based on the level of production. It incorporates a sliding scale royalty and profit split that are responsive to production levels, and minimum bonuses for each bidding round. Given its growing importance in the oil trade (buoyed by recent significant discoveries) and improved political stability, its regime is attractive.

The PSCs of Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea are based on the assumption that production levels mirror project profitability, which may not always hold. Generally, it is difficult to say if the front-end components make the three regimes non-neutral, bearing in mind the “need” for early revenue by most developing countries.

Stability

Stable policy is a key investor requirement. Angola’s and Equatorial Guinea’s PSCs provide for the negotiation of contract terms prior to signing and state participation of up to 20%. These assure predictability (by fixing the terms) and risk sharing, which may prevent adverse policy changes. Similarly, Nigeria’s PSC provides for a review of terms after an initial fifteen years, also providing stability of fiscal terms.

Furthermore, flexibility is assured by the profit related ROR sliding scale in Angola’s case. Nigeria’s and Equatorial Guinea’s PSCs target revenue, but have incorporated some flexibility by using sliding scales (production based) for profit-oil split. Nigeria’s PSC further provides for a review when oil price exceeds $20/barrel.

Therefore, while the tax regimes target some non-profit and non-positive NPV components, they still exhibit some flexibility.

Cost recovery and re-investment incentives

Cost recovery is the most important variable in a PSC (Speed, undated). Angola and Equatorial Guinea’s (new PSCs, old PSCs had no cost recovery limits) systems have cost recovery limits of 50 to 65% and 54 to 80% respectively, while Nigeria’s PSC has no cost recovery limits. They all allow for accelerated depreciation over four years (Equatorial Guinea) and five years (Angola and Nigeria). Angola and Equatorial Guinea provide for uplift on capital expenditure, while Nigerian and Equatorial Guinea allow investors carry forward unrecovered costs.

The presence of incentives for reinvestment such as ring fences (Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea), which allow for costs consolidation and uplifts on capital investment (Angola and Equatorial Guinea) ensure that incremental investments yield relatively greater returns for both parties.

Thus, the three regimes allow early cost recovery and escalation of same (through re-investment), resulting in higher revenues and favorable project economics.

Conclusion

Non-fiscal variables such as nature of the geology, stability of the terrain, product quality, ease and cost of transportation, political stability, and drilling success rates are important in fiscal regime evaluation, and make conclusions about its attractiveness more robust. For example, wide differences in government takes between two regimes may be misleading as a stand-alone yardstick for determining attractiveness, since the difference may belie wide variations in geologic, political, or business risks.

Considering the very strong endorsements in favor of the West Africa deep offshore areas in these “non-fiscal variables,” the fiscal regimes offer very attractive terms to foreign investors and explain the scramble for investment opportunities in the region’s exploration acreage.

Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea have predominantly back-end loaded taxes. Nigeria’s fiscal regime offers excellent cost recovery terms and accommodates difficulties (and costs) associated with increasing depths including royalty waivers at depths exceeding 1000 meters, while the latter offers accelerated depreciation of capital costs. Coupled with favorable geology, investors stand to gain. However, Nigeria would needs to resolve the Niger Delta crisis speedily.

Angola’s ROR sliding scale system is very progressive, but huge front-end bonuses could negatively impact full cycle economics, requiring large discoveries and/or high oil prices for an early return, or a long term view by investors. However, if government can guarantee stability, the fiscal regime is relatively attractive to investors, because investors in the oil industry would be willing to take geologic, cost and price risks, but not political risks.

About the author

Ighodalo I. Aimienwanu [[email protected]] currently resides in Dundee, Scotland, where he recently completed an MBA oil and gas management degree at the Centre for Energy, Petroleum and Mineral Law and Policy at the University of Dundee. A Nigerian by birth, he has spent nearly six years in the banking industry. However, an interest in the energy industry motivated him to undertake work on his second MBA degree.