Mergers and acquisitions complicated by new accounting rules

Seenu Akunuri Michael Collier PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, Houston

There is no question that the global energy industry is at a crossroad. Demand continues to rise around the world while many industry segments – such as deep water offshore drilling, upstream production and refining and marketing – are already operating at or near capacity. Recent turbulence in commodity prices have sharpened the focus on broadening sources of supply, yet increasing production of both traditional and alternative fuels will require significant capital investment to expand, diversify and optimize the world’s energy and infrastructure resources.

This unique confluence of events puts even the most capable management teams at a distinct disadvantage in planning for future growth. Given the volatility of energy prices, it is difficult to calculate the true, long-term value of assets and commit to additional investments. And even if internal acquisition teams are able to reach consensus on value, it may not be possible to raise the requisite amounts of capital to fund new projects or acquire assets that complement existing infrastructure.

Adding to the complication are new accounting rules that change the way mergers and acquisitions and other business combinations are reported and how fair value is measured. These new guidelines affect both corporations and private equity (PE) firms, resulting in a growing concern that business as usual will be anything but in the coming months and years.

New accounting rules

SFAS 141R - Business Combinations

SFAS 141R revises the business combination standards set forth in SFAS 141, which was introduced in 2001. SFAS 141R significantly changes how one can account for business combinations for financial reporting that might impact how deals get done in the future.

The definition of a business under SFAS 141R is more inclusive than the previous definition. Under SFAS 141R, more transactions will be treated as business combinations than under the prior rules. Under the new standard, business is defined as an integrated set of activities and assets conducted to provide a return of dividends, lower costs, increased share price, or other benefits. A business does not have to be self-sustaining (not required to generate outputs). This will require certain energy deals, such as pipelines, refining assets, power plants, development stage assets, etc., previously treated as an asset acquisition to be treated as a business combination.

Changes under the new guidance include:

- The measurement date for consideration transferred, including equity securities, is the acquisition date (the date when control is obtained, which is generally the closing date).

- Acquisition costs are treated separately from the transaction and are generally expensed when incurred. As such, companies may need to explain the nature of the related costs and the impact of such costs on the earnings of the company.

- Research and development intangible assets are initially recognized and measured at fair value and subsequently treated as indefinite-lived intangible assets, subject to amortization upon completion or impairment if the asset is subsequently impaired or abandoned.

- Earnouts, or other forms of contingent consideration, are generally recorded at fair value on acquisition date, and subsequently adjusted to fair value through earnings over time.

- Market participant basis is considered for assigning values to individual assets. An acquirer’s intentions with regard to an asset’s intended use does not impact the value assigned to the individual asset. Assets that an acquirer does not intend to use are measured on the basis of market participant assumptions.

- New disclosures are required for transactions with minority shareholders and certain non-recurring gains or losses.

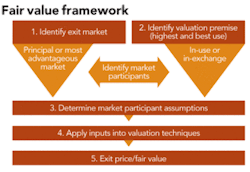

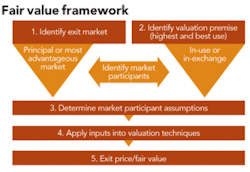

SFAS 157 introduces a new definition for fair value, which is as follows:

Fair value is the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.

Prior to SFAS 157, the definition of fair value was more ambiguous and its application was applied inconsistently. Often, practitioners valued businesses and assets assuming fair value was an entry price and made company specific assumptions at times. The definition of fair value under SFAS 157 introduces the notion that fair value is an exit price that a market participant would pay the seller for a company, asset or investment.

SFAS 157 - Fair Value Measurements

SFAS 157 allows acquirers to use one of three separate approaches to determine fair value.

- The market approach uses prices and other relevant information generated by market transactions involving identical or comparable assets or liabilities, such as the use of market multiples from comparable and similar public companies, etc.

- The income approach uses valuation techniques to convert future benefit streams, such as cash flows or earnings, to a single discounted present value amount.

- The cost approach, not generally applicable to PE funds, is typically utilized to value assets in a replacement capacity or a company in a liquidation situation.

Once one of these models is selected, SFAS 157 provides a hierarchy to prioritize the inputs to the valuation technique in use.

- Level 1 includes valuation based on unadjusted, quoted prices for identical assets or liabilities in active, accessible markets.

- Level 2 includes either a quote for an identical item in an inactive market, or a quote for similar items in active/inactive markets. Other observable inputs for full term can be used as well.

- Level 3 uses unobservable inputs – for example, a company’s own data. But the market perspective is still required.

SFAS 157 also introduces increased disclosures and documentation requirements to support conclusions of fair value. As companies move down the levels, more disclosure is required to assist investors in understanding how the asset value was determined. SFAS 157 requires companies to maximize the use of observable inputs in their valuation techniques wherever possible, and prevents them from disregarding market-based information that is reasonably available. An example within the energy sector is in an acquisition of an upstream energy company. Pre-SFAS 157, a purchaser would be inclined to utilize their own specific forward pricing curves to value the reserves of the acquiree. Upon the implementation of SFAS 157, the purchaser would now have to consider forward price curves from a market participant point of view.

The importance of valuation

SFAS 157, and to a certain extent SFAS 141R, was designed to improve the consistency, comparability and transparency of fair value measurements. By providing a single definition of fair value across US GAAP, these rules ensure that companies value assets based on market participant inputs which will require additional disclosure.

The new standards will influence acquisition negotiations and deal structures in several ways:

- Acquirers will need to consider accounting implications of acquisitions of less than 100% of the target company.

- The use of equity securities to pay for deals may be viewed as less attractive since the transaction will be measured at the close of the deal rather than at the announcement, thus pricing of the deal will not be known until closing.

- Corporate management will need to modify their accretion/dilution models to reflect the earnings impact that will result from the new standards.

- Private equity investors may want to adjust their exit strategy.

- The new consolidation standard will result in a host of new disclosures about transactions with minority shareholders and certain non-recurring gains or losses.

In times of volatility, it is easy to see the impact that SFAS 157 can have on companies. An asset’s entry price will always be the price that was paid; its exit price can fluctuate dramatically given market conditions, industry or regulatory changes and much more. The mark-to-market approach mandated by SFAS 157 may provide a more realistic, timely view of an asset’s true worth, but as financial companies are finding now, it can also create significantly more work and uncertainty for asset holders.

Potential impact on transactions

Energy companies considering M&A need to consider how a typical market participant would value a particular asset. An example is when a company is seeking to acquire another company with a significant trade name but does not plan to use it because its own trade name is more valuable. Under this scenario, the company would have to value the asset not as how it would employ the trade name upon acquisition, but on the value a market participant would sell the asset for or represent the “highest and best use” of the asset. Under the “highest and best use” methodology, if a PE fund seeks to purchase multiple portfolio companies, the PE fund would need to consider if a market participant would ascribe the most value on a stand alone basis or on a bundled basis.

In addition, companies acquiring or merging with competitors must now determine the value of the target company’s contingent liabilities, such as potential lawsuits, and revalue them on an annual basis, with any changes in value reflected in the company’s income statement.

Burden of proof

Under the new regulations, overvaluing an asset during an acquisition can lead to substantial impairment charges in future years. As the FASB continues its push for the balance sheet to more accurately reflect fair value, the burden of proof is on the acquiring firm to show, via the fair value calculations outlined by SFAS 157, that there is support for the price paid in terms of future cash flows.

Mergers and acquisitions must be handled carefully to ensure that the value of the assets purchased is consistent with the price paid; it is no longer advantageous to simply outbid competitors for an asset with the assumption that unspecified operational or management enhancements can increase its value over time.

This means that financial analysis must play a much larger role in negotiations than in the past to ensure that the acquiring company fully understands the true market value of its target. It’s widely acknowledged that, despite its challenges, reporting fair value for most financial instruments, particularly assets, provides investors with meaningful information to assess a company’s future cash flows and management’s performance. However, determining fair value under SFAS 157 for non-financial assets and liabilities can be a cumbersome task.

If the acquiring company believes there are definitive advantages to the acquisition that can enhance the asset’s value over time, then the methodology used to predict those increases in value must be disclosed. But since impairment tests must be conducted each year to determine if there is a change in fair value relative to the entry price of an acquired asset, any miscalculation of increased value, or even a change in market conditions, can require major write-downs.

Particular importance to private equity players

Private equity funds, which for the last ten years have dramatically changed the energy M&A environment, are particularly affected by M&A related accounting rules because so much of their value-creation “horsepower” is centered on the acquisition (and exit) processes. Many PE firms are investing a great deal more time and resources in the due diligence process, often working with third-party valuation consultants to determine the most accurate assessments of a target company’s assets. This allows senior management and the deal team understand the reporting/tax implications of their offer before they make it, rather than settling on a price and allocating that across assets post-merger.

In addition, PE firms may consider instituting a number of organizational practices that can help them better understand the value of their investments and provide the necessary documentation of their portfolio companies for regulatory purposes.

The first step in such an effort is the development of clear, written accounting policies and procedures along with training for all key employees. PE firms should also formalize the coordination between financial reporting valuation professionals and deal teams or asset managers, and share resources such as valuation models or other insights across the industry to enhance consistency and transparency

Most importantly, it is necessary to institute quarterly and annual fair value analysis initiatives of all assets, and document these efforts as thoroughly as possible. Any independent third-party valuation that is needed should be conducted quarterly/annually and be documented.

PE firms should designate an internal financial reporting “owner” who has clear-cut responsibilities for preparation of valuation models and memos and coordination with other relevant groups within the company, such as the valuation committee, deal teams, asset management teams and senior management. Valuation memos should include:

- A complete description of the subject company.

- A complete description of the investment, including rationale, acquisition multiple, complete capital structure and co-sponsors.

- An overview of the investment’s financial performance, including pro forma at acquisition, historical and prospective financial performance and budget vs. actual.

- Management’s outlook and expectations for the investment, including an overall industry perspective; revenue, EBITDA, growth and margin expectations; and unanticipated events, such as potential lawsuits or contract expirations.

Finally, the valuation process including methodologies, support for significant assumptions, exit strategies and substantiation of concluded values should be reported and documented.

What the future holds

Indeed, some PE firms are changing their investment strategy due to a decline in leveraged buy-outs resulting from the credit crunch impacting our economy. PE firms are focusing on distressed assets and are actively seeking to purchase divisions of other PE firms or corporations rather than acquiring whole companies as corporations seek to return to their core competencies.

At the same time, however, some PE funds are moving ahead with aggressive acquisition strategies in an attempt to capture the value inherent in today’s energy and power markets.

Regardless of what happens to commodity prices, it is clear that PE firms and others involved in energy M&A must approach potential targets with a clear-cut, definitive understanding of the value of assets they are purchasing.

More and more, due diligence teams are having in-depth discussions with third-party valuation consultants to help determine tangible and intangible values and to structure deals properly to minimize the risk of future impairment charges.

In addition, PE firms will need to implement management oversight and policies and procedures to ensure proper valuation on an ongoing basis of all assets. With the appropriate structure in place and clear and well defined exit strategy, PE funds can continue to invest in the energy sector markets and do so successfully.

About the Authors

Seenu Akunuri [[email protected]] is a director in the Transaction Services group of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP.

Michael Collier [[email protected]] is a partner in the Houston Transaction Services group of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP.