Executive compensation arrangements

E&P companies continue to walk the line Brian Cumberland and JD IVY, Alvarez & Marsal, Dallas

Designing compensation programs that retain and motivate key executive talent, while simultaneously maximizing shareholder value, is a challenge all public companies face. Responsibility for walking this precarious line falls to both members of the management team and of the compensation committee of Boards of Directors (Compensation Committees). Due to a volatile commodities market in the energy sector, restructuring pay packages can be a daunting task. The goal is to restructure pay packages to avoid an avalanche of key executive departures, all while facing the ire of third party shareholder advisors, the media, and political activists asserting that executive pay levels are unjust and excessive.

To do that, companies must ensure compensation programs are reasonable and specifically tailored to their organizations. This can be accomplished by analyzing the competitiveness of the arrangements (as compared to those offered by companies in its peer group), and the likelihood that executives will be sufficiently motivated in both the short and long-term. Understanding how competitors compensate their executives is a critical step in this process.

THE E&P Incentive Compensation Report

To identify how exploration and production (E&P) companies compensate their CEOs and CFOs, the Executive Compensation Practice of Alvarez & Marsal conducted a comprehensive survey of executive compensation arrangements in place at the 100 largest publicly traded E&P companies in the US. Only companies that derived a majority of revenue from E&P activities and disclosed sufficient executive compensation data were included in the analysis.

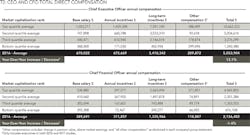

We divided the companies into four quartiles based on market capitalization (see Table 1), and made comparisons to our prior studies, when applicable.

Executive compensation programs at E&P companies

Executive compensation programs at E&P companies include: (i) base salary, annual bonus, and long-term incentives (Total Direct Compensation); and (ii) change in control benefits (CIC Benefits).

Total Direct Compensation. On average, Total Direct Compensation paid to CEOs was up 13%, which was primarily due to increases in the grant date fair value of long-term incentives. Average Total Direct Compensation paid to CFOs fell slightly (down 1.4% to $2,156,402). See Table 2.

As in prior years, approximately 80% of Total Direct Compensation paid to CEOs and CFOs was derived entirely from incentive compensation. Base salary and/or other forms of compensation, such as increases in the value of retirement plans, made up the remaining 20%. On average, base salary accounted for 13.2% of Total Direct Compensation paid to CEOs, and 18% to CFOs.

Incentive Compensation. Properly structured incentive compensation arrangements are effective in retaining and motivating executives over different periods of time. Annual incentive plans (AIPs) measure short-term performance (generally, over a one-year period) and long-term incentive plans measure performance over longer multi-year periods. Additionally, incentive compensation that is contingent on the achievement of established performance criteria is generally exempt from the $1 million deduction limit that applies for Federal income tax purposes.

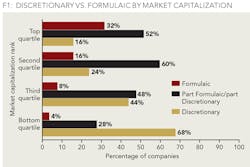

Annual Incentives. Annual bonus plans generally fall into one of three categories, those with payouts based on a formula (Formulaic Bonus Plans), Compensation Committee discretion (discretionary Bonus Plans), or a combination of both (Combination Bonus Plans).

In Formulaic Bonus Plans, bonus amounts are contingent on the achievement of set performance criteria and targets. Compensation Committees do not have discretion to increase payout amounts, but they are given authority to exercise negative discretion (i.e., to reduce amounts actually paid). The prevalence of these plans remained relatively flat between 2014 and 2016 (14% in 2014, 17% in 2015, and 15% in 2016).

Once quite common, the prevalence of Discretionary Bonus Plans declined 17% between 2014 and 2015. In 2016, 38% of companies have a Discretionary Bonus Plan, up slightly from 2015 (37%). Figure 1 shows the breakdown for each quartile.

Combination Bonus Plans incorporate both a formula, which is used to calculate the size of a bonus pool (for example, a percentage of EBITDA), and discretion to allocate such funds to individual executives. In 2016, 47% of companies used Combination Bonus Plans, as opposed to 32% in 2014. The rise in prevalence is likely due to the need for some flexibility to respond to unforeseen circumstances or factors outside of an executive's control, like crude oil and natural gas price fluctuations.

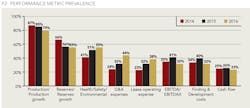

With respect to performance metrics used in annual incentive plans, companies appear to be favoring cost control metrics, and may be shifting away from tying incentives to growth without considering underlying profitability. In 2016, the three most prevalent performance metrics were: (i) production and growth in production (used by 79% of companies, down from 85% in 2015); (ii) reserves and reserves growth (used by 55% of companies, down slightly from 56% in 2015); and (iii) health, safety, and environmental metrics (used by 55% of companies, up from 51% in 2015). Compared to previous years, companies were more likely to tie bonuses to growth or production in existing, successful wells, reducing unprofitable production efforts, and expense reductions (see Figure 2).

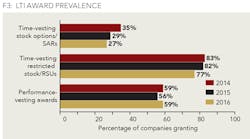

Long-Term Incentive Plans. As a long-term retention and motivation tool, equity-based long-term incentives (LTI) align an executive's interests with those of shareholders. Stock options, stock appreciation rights (SARs), restricted stock and restricted stock units (RSUs) are the most common forms of LTIs.

In 2016, 77% of companies granted restricted stock and RSUs that vest on the basis of time, 59% of companies used performance-based awards, and 27% of companies awarded time-based stock options and SARs (see Figure 3).

In an effort to ensure total compensation values remain competitive, some companies that grant performance-based awards or stock options will, in tandem, provide executives with time-based restricted stock or RSUs. The majority of E&P companies (67%) granted two or more different types of LTI.

Almost half (44%) of all performance-based awards were contingent on the achievement of more than one measurement of performance. Most awards (92%) were based, at least in part, on total shareholder return (TSR) as compared to the TSR of its peer group (Relative TSR). One-third (32%) incorporated TSR on an absolute basis (Absolute TSR), designing it as either a standalone metric or, if Absolute TSR was negative, as a lower cap on maximum allowable payouts. Companies also implemented metrics based on production (10%) and reserves (7%).

Why companies pay as they do

Looking at the data, we asked why the companies pay as they do.

The companies generally use the structure of, and pay consistently in amount with, the US pay model. In general, higher amounts are paid at companies with greater market capitalization - reflecting the differences in complexity and affordability (considering pay as a percentage of market capitalization), and the pay structure is more leveraged or variable.

Annual Incentive Plan (AIP). The AIP at larger companies is generally formulaic or a combination of formulaic and discretionary, but more discretionary at smaller companies. Larger companies tend to use a design that preserves Federal income tax deductibility (as performance based), yet provides flexibility to deal with performance variability caused by economic market conditions.

Production and reserves growth is the essence of the business - a commodity production business. Given the suppressed price of oil and gas, there is an imperative to operate efficiently, so it is prevalent to include efficiency or profitability metrics. Also, because of the nature of the industry, safety and environmental goals are important. These operational features round out the prevalent mix.

Long-term Incentives (LTI). The industry uses TSR as the prevalent metric for awarding long-term equity. Large capitalization companies predominantly use relative TSR - as a "performance measure of choice." This is consistent with the commodity nature of the business. The value of an E&P company's reserves and current and future production is valued and given liquidity through the public stock market. Changes in equity value are a combination of external market forces, internal management activity, and costs of finding and extracting the commodity based on physical conditions. To a reasonable degree, the industry has enough different member companies that reasonable peers for comparison are available, so a relative TSR program creates alignment, and is engaging and rational to both executives and shareholders. It also works well in the current governance environment that demands executives not be paid ahead of shareholders.

Both large- and small-capitalization companies use absolute TSR and/or stock options. The use of absolute TSR or stock options recognizes the limitations of the relative TSR metric (such as the comparability of the comparison group or the relative volatility of a specific company's business model and risk profile). A company may enjoy more steady, less volatile TSR performance over time, and a stock option may better accommodate and pay for that steady performance. Also, some small companies may see a particularly promising growth opportunity for an extended period of time, and a stock option provides leverage and specificity that is particularly engaging to that company's executives.

Finally, the industry uses restricted or time-based stock to sure-up retention in the current, challenging environment. Even though the industry as a whole is depressed, receiving fresh, new equity awards at another company at/or near the bottom of the cycle can be an attractive prospect for some executives. Therefore, companies need to provide key talent with a reason to stay and remain engaged and time vesting stock is generally most effective at accomplishing this objective.

What Do We Expect in 2017? The economic outlook for the industry appears to be brightening, but guardedly so. Oil and gas prices are off their lows, some capacity has been sidelined, and international producers seem to be behaving more rationally.

We expect large-caps to continue to pay as they have in recent years-in design, structure, and amount. As prices stabilize we anticipate that companies will be able to set more realistic incentive targets, which should lead to stronger annual and long-term incentive payouts.

Small-capitalization companies that have been particularly constrained-lower pay amounts, and no LTI or cash-based LTI-will gradually recover if oil and gas prices can stabilize. In the meantime, we note:

- Misery loves company. Other small-capitalization companies in our study are struggling with compensation issues e.g., many small capitalization companies granted no LTI for two consecutive years.

- Companies should focus on pivotal management roles, e.g., critical personnel and high performers/high potentials.

- Many executives will stay if they believe they are making a difference, and they are receiving a reasonable level of compensation.

- Compensation Committees need to communicate regularly with shareholders; proxy advisers have plenty of advice, but have never paid an E&P company's executives; so stay informed of advisors' voting policies, avoid pay irritants, and "protect the core" compensation program.

Bankruptcy compensation. Of particular importance to E&P companies is the impact plunging commodities prices had on their stock prices. In some cases, equity value fell by more than 50%, pushing LTI values into the gutter. The impact is clear when the average value of restricted stock and performance share awards made to the top 20 E&P CEOs is compared to declining crude oil and natural gas prices. We view executive compensation as one of the most important levers available in a restructuring.

Change in control benefits. Most E&P companies also provide change in control benefits, which generally include one or more of the following: (i) cash severance; (ii) the accelerated vesting of outstanding, unvested equity awards; (iii) the vesting of certain retirement benefits; and (iv) excise tax protection. For CEOs and CFOs, severance payments and long-term incentives represented more than 80% of the value of CIC benefits. Due predominantly to lower stock prices, average total CIC benefit values for CEOs declined in 2016 (to $8,849,145, down 7.6% from 2015), and for CFOs (to $3,437,059, down 1.4% from 2015). See Table 3.

Cash severance payments. Cash severance payments upon a termination of employment in connection with a change in control are provided to CEOs in 72% of E&P companies, and to CFOs in 68% of E&P companies. Severance payments are generally expressed as a multiple of compensation, which is most commonly defined as either base salary, or base salary plus annual bonus. CEOs were entitled to severance equal to: (i) three or more times compensation (at 47% of companies); and (ii) between two and three times compensation (at 46% of companies). Severance for CFOs was: (i) between two and three times compensation (62% of companies); and (ii) three times compensation or higher (23% of companies).

Accelerated vesting. The prevalence of single and double trigger vesting provisions in equity plans were nearly the same in 2016. Single trigger vesting (i.e., vesting on a change in control) was found in 47% of equity plans. A double trigger (i.e., a change in control and an involuntary or constructive termination of employment without cause, or a resignation for good reason) was used in 46% of equity plans. Only 7% of companies granted the Board discretion to accelerate vesting. However, as pressure from shareholders and shareholder advisory services continues to mount, more companies are expected to transition to double trigger vesting provisions.

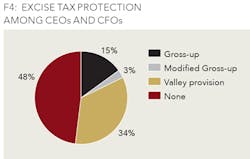

Tax Gross-ups. In accordance with the "golden parachute" provisions in Section 280G of the Internal Revenue Code, payments to executives that exceed the "safe harbor" threshold trigger a 20% excise tax on the executive and a disallowance of a tax deduction for such amounts by the company. Due to the scrutiny placed on this benefit, fewer companies are authorizing them. In fact, 48% of E&P companies declined to provide executives with any form of excise tax protection in 2016 (See Figure 4). However, these protections are often negotiated prior to an actual transaction.

Conclusion

The E&P industry has experienced a great deal of turmoil over the last several years. As it should, this has had an effect on how companies compensate their executives. As the industry hopes for better times, it is still being cautious with the manner in which it is compensating executives. If and when commodity prices stabilize, Compensation Committees will be able to more easily align executives' interests with the direction of the business by effectively setting performance goals and targets. Until that time, Compensation Committees will continue to struggle with identifying the most effective way to align executive compensation with business results.

About the authors

Brian Cumberland is a managing director with Alvarez & Marsal LLC in Dallas, where he leads the firm's Compensation and Benefits practice. Prior to joining A&M, Cumberland led KPMG's Compensation and Benefits Group for the Southwest. He earned a bachelor's degree in business administration from the University of Texas and a juris doctor from St. Mary's School of Law. He also received a master of laws degree in taxation from the University of Denver.

J.D. Ivy is a managing director with Alvarez & Marsal LLC. Prior to joining A&M, Ivy was a senior manager in the compensation and benefits groups of KPMG and Arthur Andersen. Ivy received a bachelor's degree in accounting from Abilene Christian University and a master's degree in business administration from Texas Tech University. He is a Certified Public Accountant, and a Certified Compensation Professional through the World at Work organization.