Does size matter?

RETHINKING THE SIZE OF YOUR ASSET TEAMS

JAMES BAMFORD, JOSHUA KWICINSKI, AND MARTIN MOGSTAD, WATER STREET PARTNERS, WASHINGTON, DC

NON-OPERATED ASSET TEAMS are under assault. Staring into low commodity prices, non-operated asset teams in petroleum, minerals, and other natural resource sectors are under pressure to reduce team size.

Attempting to shelter their teams - and make a fair and fact-based determination of the right team size - many non-operated asset managers and executive sponsors lack the data and perspectives to do this well.

It doesn't have to be this way.

UNDERSTANDING RISK IN A POST-MACONDO AND SAMARCO ENVIRONMENT

Assets can have very different technical risk profiles; for example, developing an onshore conventional oil and gas asset is inherently less risky than an offshore Arctic oil and gas exploration well or one in deepwater Gulf of Mexico. Closely related to value or upside is the risk profile of the asset or downside. Non-operators post-Macondo and Samarco increasingly understand the financial and reputational impacts of Health, Safety, and the Envrionment (HSE) incidents. On the whole, this suggests that assets with greater HSE and technical risk likely need a larger team providing assurance and leaning in on critical issues.

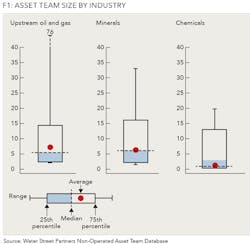

Non-operated asset teams typically range from two to eight FTEs. Teams in the oil and gas industry tend to be twice as large as teams in mining, chemicals, and other natural resource industries, according to data Water Street Partners has collected and synthesized on team size in more than 250 non-operated assets across the natural resources sector (See Figure 1). And asset teams looking after joint venture (JV) operating companies-incorporated businesses with an independent management team-are usually twice as small as asset teams looking after unincorporated JVs operated by a partner (See Figure 2).

Ideally, non-operators thinking about asset team size would engage in a process that begins with benchmarking-but then goes further, in search of the context and nuance necessary to differentiate assets otherwise similar on paper, and to enable companies to identify situations where greater resourcing might generate real value-or where no amount of expertise will ever shift the operator's path. We believe this calls for a greater focus on three things that provide a more holistic understanding of the asset and the implications of more or less resourcing: value, risk, and influence.

NO VALUE, NO TEAM

Value is the sine qua non for an asset team-no value, no team. That value can be quantified across multiple dimensions, including the well-known financial metrics like Net Present Value (NPV) and Free Cash Flow (FCF) that drive daily decision-making across the industry.

But pure statistics are only the starting point. Consider two assets with similar NPV on paper. One asset is mature and focused on managing the decline curve using proven approaches, while the other is months away from the Final Investment Decision (FID) on its initial development plan featuring $500 million company share. Despite the same NPV, more value in the near-term is in play for the second asset. Meanwhile, an asset may have a relatively small carrying value or limited near-term spend. But an asset may be worth investing resources in due to the strategic benefits-like gaining favor with a National Oil Company (NOC) in the future by over-investing in providing technical support today in an asset the company operates.

YIELD INFLUENCE, ACHIEVE DESIRED OUTCOMES

The third factor is the company's level of influence on the operator. On occasion, non-operators have extremely strong formal rights-like veto, information access, audit, and other rights in the Joint Operational Area (JOA)-that can be leveraged to achieve desired outcomes. More often, the ability to influence an operator is a product of more informal levers-like grudging respect earned through demonstrated technical competence, relationships built over the long-term, or the ability to offer a valuable carrot in trade.

Understanding the level of influence is a critical input into an asset's team size. All else being equal, more resources should be placed on the asset where the company has greater influence-and more ability to impact value and risk. On the other hand, a company with no influence and significant risk ought to be staffing just enough to provide assurance-while asking whether it should remain in the asset at all.

TEAM SIZE IS STILL ONE OF MANY FACTORS

Looking at value, risk, and influence provides a thoughtful way to have a conversation about resource allocations, and enables cross-asset comparisons, identification of assets whose resourcing seems disconnected from key factors, and a framework and language to defend headcount against executives challenging from afar without context.

Make no mistake, team size is just one factor determining non-operating partner success. Asset team composition, seniority, dedication, structure, and several other factors also matter. Size is the easiest to change, and possibly the most impactful in the near term. In the end, size does matter.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jim Bamford is a co-founder of Water Street Partners based in Washington, DC, where he serves a global client base across industries on joint venture issues. He has supported more than 200 JV transactions and restructurings during his career and has worked extensively on JV governance, organizational, and commercial matters. Prior to Water Street, he co-led the JV practice at McKinsey & Company.

Joshua Kwicinski is a senior director at Water Street Partners has led multiple engagements on JV governance with IOCs, NOCs, and other natural resources firms. He also serves a global client base in aerospace and defense, biotechnology, hi-tech manufacturing, and other industries.

Martin Mogstad is a senior consultant with Water Street Partners. His recent experience includes working with oil and gas operators, service companies, and heavy industry manufacturers in North and South America, Europe, and the Middle East. He joined Water Street Partners from Schlumberger, where he worked in business consulting.