Dealing with corruption

Use extreme caution when entering into international, high-risk transactions

MARK JENKINS, GLASSRATNER ADVISORY & CAPITAL GROUP LLC, DALLAS

I typically get a bit excited about movie sequels despite their historically bad reputations. I have enjoyed a few: "The Empire Strikes Back," "Aliens," Star Trek II - Wrath of Khan," "Godfather II" and the highly anticipated sequel to Ridley Scott's "Blade Runner." What about corruption scandals? Do they have sequels? Of course they do!

In the last four years, Brazilian federal prosecutors have had their courtroom dockets full of bribery and kickback cases related to Petrobras, the Brazilian state-controlled oil company. The Brazilian federal police nicknamed the Petrobas investigation, "Operation Lava Jato" or "Operation Car Wash".

Now we have a second scandal - Eletrobras, the Brazilian state-controlled power company, which produces electricity through electric, hydro and nuclear power plants. It has been quietly involved in the follow up investigations with code names such as "operation radioactivity" and "operation electroshock". It has promises of similar notoriety to Petrobras; but has not received as much media attention.

Similar to Petrobras, Eletrobras involves federal prosecutors arresting high-level executives, construction companies involved in scandal, and a civil class action lawsuit for securities violations.

Petrobras

However, I am getting ahead of myself. To best understand the Eletrobras scandal, it's important to get a grasp on the Petrobras scandal. They are interrelated and overlap.

The name "Operation Car Wash" originated from a gas station two miles west of Brasilia's government buildings called Posto da Torre or Tower Gas Station. The Wall Street Journal reported in June of 2015 that a money transfer services allegedly used to transfer bribe payments from Petrobras to Petrobras executives' offshore accounts was on the premises of the gas station.

The Original Scheme

According to the US Department of Justice (DOJ), the Petrobras scheme of bribes and kickbacks came in part through a system put in place by Odebrecht and its subsidiary, Braskem, a Brazilian construction company. Odebrecht created a division called the "Division of Structured Operations" (DSO), which operated solely to collect and disburse funds to pay bribes.

Off-book transactions and secret encrypted email communications were utilized to conceal the activity from outsiders. Court documents reveal that the generation of funds to pay the bribes came from intercompany overhead charges, retainers for the purchase of company assets, and self-insurance charges.

According to the DOJ, Odebrecht alone paid bribes in Brazil of at least $349 million to obtain $1.9 billion in benefits such as the awarding of contracts and favorable legislation. Outside of Brazil, Odebrecht paid bribes of $439 million to foreign government officials in at least 11 other countries in Latin America and Africa to obtain $1.4 billion in benefits. Odebrecht has pleaded guilty and has agreed to pay a total of at least $2.6 billion and up to $4.5 billion dollars in fines depending on its ability to pay. Braskem has pleaded guilty and has agreed to pay a total criminal penalty of $632 million and $325 million in disgorgement of profits.

Eletrobras

As part of the plea bargains agreed to in Operation Car Wash during 2014 and 2015, several construction company executives admitted to bribing Brazilian state-controlled companies in other sectors. During testimony in 2015, Dalton Avancini, CEO of Camargo Correa SA, stated that [Petrobras] bribes were paid to Eletrobras executives by Camargo Correa SA on a hydro dam project called Belo Monte and a nuclear reactor construction project called Angra 3. Two months later Ricardo Pessoa, owner of UTC, another construction company, also testified that his firm paid bribes to Eletrobras officials for the Angra III project.

On May 14, 2015, Eletrobras issued a disclosure to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) stating it would not be able to file its financial statements with the SEC in part due to the internal investigation of the bribery allegations. In July 2015, Brazilian law enforcement arrested Othon Luiz Pinheiro da Silva, CEO of Eletronuclear, a subsidiary of Eletrobras, for 24 instances of rigging bids for the Agra III project in return for R $4.5 million (USD $1,137,600) in bribes. On August 15, 2015 the City Of Providence, Rhode Island, brought a class action lawsuit against Eletrobras for violating the Securities Exchange Act 1934 for concealing the Eletrobras corruption issues, and misleading investors.

In May 2016, the New York Stock Exchange suspended trading of Eletrobras securities and began delisting procedures due to the failure of Eletrobras to file its 2014 financial statements. The acting Eletrobras CEO, Pedro Figueredo, who had taken over for Pinheiro after his arrest the prior year, was suspended in July 2016 from Eletrobras. He was being investigated by Brazilian police for collusion with Pinheiro in the bribery scheme and interfering with the investigation. In October 2016, Eletrobras released their 2014 and 2015 financial statements with the following message:

"...our 2014 and 2015 consolidated financial statements reflect the conclusions of the Investigations which resulted, respectively, in the expensing of costs of R$ 195.127 million (approximately USD 73.4 million) and R$ 15.996 million (approximately USD 4.04M) that had been improperly capitalized to our assets. "

Also stated in the 2015 financial statements was a comment, which had been included in the last several years' financial statements:

"As a result of our management's evaluation of the effectiveness of our disclosure, controls and procedures in 2015, our management determined that these controls and procedures were not effective due to material weaknesses in our internal controls over financial reporting."

Compliance takeaways

As a multinational company or even a business entity that is contemplating entering international trade, how do you avoid scandals described above? How-or could-a robust compliance program uncover widespread corruption involving several levels of management going all the way to the top?

For the numerous entities and subsidiaries involved in the aforementioned investigations, it is difficult to determine what compliance programs were in place, if any, and when the compliance programs began. Eletrobras stated they had a compliance program, however, as previously mentioned, Eletrobras management stated that their internal controls had not been adequate in 2014 and 2015.

Compliance "Must Haves"

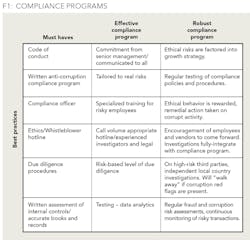

Companies that have United States and foreign regulatory mandates such as Sarbanes Oxley, DOJ, SEC, and Brazil's Clean Company Act should have the minimum requirements in place (see first column in Figure 1). An effective compliance program must go beyond what is standard and have top-level commitment, compliance testing, and a risk-based compliance program (see second column in Figure 1). The third column represents seasoned multinationals that understand corruption risks and thrive on the additional scrutiny by law enforcement globally. Their compliance programs factor in corruption risk as part of their overall strategy. They continually monitor high risk transactions and incentivize their employees to conduct business ethically.

Internal controls/due diligence

Anti-corruption policies are only as effective as the internal control and compliance procedures that test if employees are following the policies. Below are a few examples of internal control/compliance procedures that can assist you in validating that your organization has "above board" transactions:

Construction bid review

International construction projects in high-risk countries involving foreign governments should be considered high priority for review. For public bid government projects, determine if bid procedures were followed including:

• Obtain at least three bids with the same bid specifications sent to each bidder for construction projects over a certain dollar amount.

• Segregation of duties: The person sending out the bid information (such as an engineer) is not the same person that should receive and analyze bid packages. A third employee with no interests as to the outcome should choose the winner based on quality and price.

• Quality and due diligence investigations conducted on bidding companies to determine appropriateness of the bidder, potential conflicts of interests, history of corruption, and bid history results.

• Market and comparison analysis conducted on purchased equipment and services of winning bidder to identify potential overcharges.

• Conduct change order analysis frequency/amounts post bid.

High risk transactions

There are certain transactions (txns) that have a great susceptibility for corruption. Figure 2 shows several typical high-risk transactions and potential guidance on how to review them.

Anti-corruption due diligence third parties

For high risk third parties which includes agents (in high corruption risk countries) that are providing introductions to government entities, there should be a higher level of due diligence (See Figure 3).

Of special note, accepting at face value information provided by a third party without verifying the accuracy is not considered real due diligence. This would be considered "papering the file" and will not be accepted by regulatory agencies when an investigation commences and therefore should not be accepted by compliance professionals.

The 2016 Unaoil scandal validates the argument that compliance cannot be a "check the box" exercise. In this instance, internal emails went public showing that it may have been an intermediary for bribes involving numerous corporations.

Independent transactional testing

Along with the internal review processes mentioned above, data analytics testing will assist with ensuring your anti-corruption program is operating effectively. Conduct prioritized data analytics testing based on high-risk divisions, vendors/agents (based on type and monetary amounts paid), or locations. Test project purchase order and invoice data including quantity, pricing, and descriptions while comparing to other arms-length transactions with review by third-party objective experts. For example:

- Look for low digit and/or consecutive invoice numbers (indicating that you might be the only customer for a vendor or potential shell company).

- Identify potential duplicate invoices by examining those with the same date and amount for invoice numbers such as "1a" or "2b".

- Use Benford's law (also called the first-digit law), an observation about the frequency distribution of leading digits in many real-life sets of numerical data. The law states that in many naturally-occurring collections of numbers, the leading significant digit is likely to be small. Test invoice amounts for unnatural frequencies of specific digits with the same significance. For example, if you observe multiple amounts just below approval thresholds such as $24,999, $249, and $24, the second digit, "4", has an occurrence greater than is natural according to Benford's law. Such behavior may be indicative of an attempt to circumvent approval processes for purposes of making corrupt payments.

- Also, compare project vendor addresses with those of other vendors, employees, and related parties to identify potential conflicts of interests.

Based on investigation of data analytics testing results, eliminate false positives and perform "on the ground gum shoe" investigating. For example, if you find two bidders that are consistently winning bids, visit the location. In parts of Latin America, different addresses and vendor names can lead you to the same location. Site visits can also provide you with information on whether the vendor can actually provide the service or manufacture the product. A residential address that is billing for large power generators may be either a distributor or a false vendor. In addition, verify that the product or service was actually delivered and/or provided.

Postscript

As of the date of this article, it is unknown what the conclusions will be of the known ongoing investigations by Brazilian authorities of Eletrobras. There is a continuing Eletrobras internal investigation, and it is unknown what will transpire, if anything, regarding the pending class action lawsuit.

In the meantime, the Petrobras scandal does not seem to be going away. In February 2017, Panamanian investigators raided law firm Mossack Fonseca offices, the integral player in the "Panama Papers" scandal. Ten months before the raid, documents were leaked implicating companies and individuals using the law firm as a safe haven for tax evasion. Now there are allegations by Panamanian and Brazilian authorities related to Odebrecht bribe payments being connected to Fonseca.

Verify before entering into international, high-risk transactions that you have a robust and risk-based anti-corruption compliance program with sufficient internal controls in place so your organization can avoid the "film noir" atmosphere encountered by these Brazilian business entities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Jenkins is a senior managing director in the Dallas office of GlassRatner Advisory & Capital Group LLC. He has more than 20 years of experience in forensic accounting, financial investigations, fraud risk assessments, anti-corruption consulting, and financial analysis. He has in-depth knowledge and skills in managing litigation projects and investigations in both domestic and international environments with extensive experience in Latin America. He regularly provides global anti-corruption due diligence and training to international business entities. Before joining GlassRatner, Jenkins co-founded Fidelity Forensics Group LLC, a forensic accounting, investigations, and anti-corruption consulting firm.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or positions of GlassRatner Advisory & Capital Group LLC or of Oil & Gas Financial Journal.