The race to liquids

E. Russell "Rusty" Braziel, Bentek Energy, Evergreen, Colorado

For the past 18 months, the cash price for natural gas at the Henry Hub has averaged less than $4.25/MMbtu. Even the most optimistic, bullish members of the producing community have grudgingly recognized that the shale gas phenomenon is materially shifting the natural gas supply/demand balance.

Natural gas producers drilling in shale and other unconventional plays continue to improve productivity, lower costs, and increase output. Growth in natural gas supply is primarily responsible for the lower market price for natural gas today and will likely maintain downward prices for some time to come.

Fortunately for some producers, there is more than just methane in those shale formations. Some contain high quantities of natural gas liquids (NGLs) and condensates, and both products have prices more aligned with crude oil than natural gas. With crude oil prices historically high relative to natural gas, high-BTU NGLs and condensates yield a much higher wellhead value for the producer.

Over the past year, this premium value has resulted in a veritable "Race to Liquids." Most of the larger shale gas producers have shifted significant budget dollars to liquid-rich plays, including both high-BTU gas and crude/condensate production with high-BTU associated gas.

But there is a catch. For some it is a big one. To realize the higher wellhead value for high BTU gas, the producer must run what Bentek calls the "NGL Value Chain Gauntlet." NGLs must be extracted at a processing plant, the liquids must be fractionated (split into individual NGL components), transported to market, and finally, that market must be large enough to absorb the new supply without a detrimental impact on price.

Producers in areas suffering downstream capacity constraints may find the economic benefits of high-BTU gas will be difficult to realize. Worse yet, in some cases, such constraints can be so severe it may restrict the volume of gas that can be produced, setting a limit on the number of wells that can be drilled and completed.

As natural gas production from high-BTU plays continues to increase, the possibility of capacity limitations and market oversupply will increase. Market participants need to be vigilant to spot the early warning signs of these developments.

Lower natural gas prices

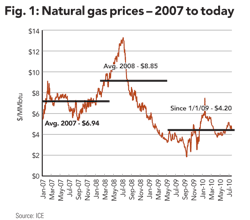

Compared to the recent past, natural gas is cheap. As shown in Figure 1, the average cash market price of natural gas at the Henry Hub in 2007 was $6.94/MMbtu. During the commodity price run-up in early 2008, the price rose to almost $14.00/MMbtu. Then with the financial meltdown during the last half of 2008, prices fell precipitously. The average price of natural gas in 2008 was $8.85/MMbtu.

By January 2009, the price was below $5.00 and has remained there for most of 2009 and the first half of 2010. During the 18 months since January 2009, the natural gas price has averaged $4.20/MMbtu. The reasons for this decline are complex and multifaceted. One of the primary factors is clearly a continuing oversupply of natural gas due to prolific production from shale plays.

In recent months, producers have begun to recognize that the current low price environment for natural gas could persist for quite some time. As a result, producers are pursuing strategies that will increase their revenues from each unit of wellhead production. One of the most successful of these strategies has been a shift of drilling budgets and resources to high-BTU gas plays, and to crude oil opportunities with high-BTU associated gas.

The following quotes taken from investor conference calls from early in the second quarter 2010 reflect this drilling sector sentiment:

- Chesapeake: "We continue to focus primarily on oil and liquids rich areas. That's where the money is these days…..For now, we are disclosing just 12 liquids rich plays, but there are more on the way."

- Devon: "Oil and NGL are the focus now. Most of 2010 is focused on oil and liquids-rich plays"

- Petrohawk: "2,000 drill sites in the Eagle Ford should be crude oil and liquids rich. While crude oil and natural gas liquids are a small part of our production today, we can grow it quickly..."

These are only a few examples. Many other producers are jumping on the liquids bandwagon.

Relationship between crude and natural gas prices

The value driver for high-BTU natural gas is the price relationship between crude oil and natural gas. The price of NGLs is strongly influenced by crude oil prices. When crude oil prices are high relative to natural gas, NGL prices tend to be equally strong.

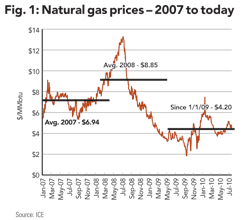

In pure BTU terms, a barrel of crude oil contains about six times the heat energy of an MMbtu of natural gas. But for several decades that relationship has had little to do with pricing. For the past 20 years, the crude-to-gas ratio has averaged just under 10:1. That ratio increased significantly starting in early 2009, ramping up to almost 25:1 in September of last year.

More recently, the ratio has pulled back to about 17:1, which is still quite high historically. The considerably higher ratio over the past two years reflects both the dynamics of the global crude oil market and the shale-induced oversupply of North America's natural gas.

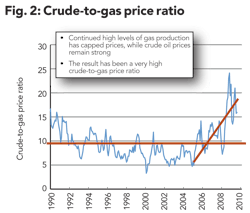

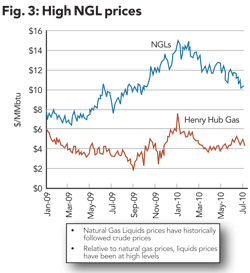

Figure 3 indicates how the relative strength in crude prices is pushing NGL prices well above the price for natural gas. The blue line is the weighted average price for a basket of NGLs based on the average natural gas plant slate of products — 45% ethane, 30% propane, 10% normal butane, 5% isobutene, and 10% natural gasoline. Pricing for this basket fluctuated between $7 and $14/MMbtu during the period since January 2009, while natural gas prices averaged the $4.15/MMbtu previously referenced.

Note that almost half of the average barrel of gas plant NGL production is ethane. Ethane is an especially significant NGL product for three reasons:

|

NGL producer liquids credit

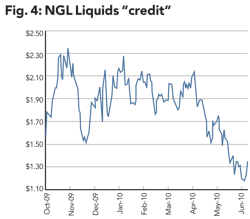

How much can higher value NGLs mean to a natural gas producer? One way of looking at this value is to compute the NGL "producer credit" — defined as the incremental margin that a natural gas producer can receive by extracting the raw natural gas stream and selling the liquids from production.

Consider the following example: A producer has two wells in the same region. Well #1 produces pipeline quality gas, approximately 1,050 btu/cf. Well #2 produces high-BTU gas — 1,300 btu/cf. Gas from Well #2 can be processed, fractionated, and transported to market in Mont Belvieu (major trading hub for NGL on the Texas Gulf Coast) for a total cost of 10 cents/MMbtu.

The incremental margin of Well #2 over Well #1 since October 2009 is shown in Figure 4. Over this period of time, our producer realized a netback of approximately 1.50/MMbtu more for gas from the high-BTU well. Said another way, the effective break-even price (the natural gas price at which the producer makes an acceptable rate of return) is $1.50 LESS for the high-BTU well. (Recent weakness in the Producer Liquids Credit, which at the time of this writing is about $1.50/MMbtu, is primarily due to some strength in natural gas prices as a result of primarily weather-related demand.)

Evidence of the shift in natural gas drilling activity

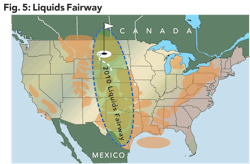

There is ample evidence in reported drilling data that the shift to higher-BTU plays is well underway. In fact, much of that shift is concentrated in an area of the country that runs from South Texas almost due north to southern Saskatchewan in Canada (see Figure 5).

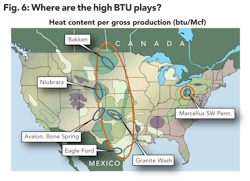

This "Liquids Fairway" includes the following new natural gas plays that are often talked about in today's natural gas marketplace (see Figure 6), including:

- Eagle Ford in South Texas

- Granite Wash in the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles

- Avalon and Bone Spring in the Permian basin

- Niobrara in Colorado and Wyoming

- Bakken in North Dakota

Figure 6 also indicates the average BTU value of many of the major US producing basins. Low BTU basins are shown in purple, while higher BTU regions are shown in dark green. Most of the higher BTU regions are within the Liquids Fairway, but not all.

Note: There is one important high-BTU producing region that does not fit into the Liquids Fairway and encompasses a portion of the Marcellus shale basin located in western Pennsylvania, eastern West Virginia, and extends into western New York. Like plays in the Liquids Fairway, the high-BTU Marcellus region has the potential to add incremental value to the producer's netback. But high-BTU gas in the Marcellus is far removed from almost all petrochemical markets and has been consistently plagued by limitations on processing and fractionation infrastructure. The implications of these constraints will be discussed in greater detail in the section below titled 'The NGL Value Chain Gauntlet.'

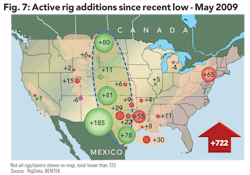

Hard evidence of the shift to the Liquids Fairway can be seen in the deployment pattern of drilling rigs, as indicated in Figure 7. This graphic shows areas where new natural gas drilling rigs have been added since May 2009, when the rig count dipped to a low point due to the economic meltdown and inception of lower prices. The data indicates that 722 natural gas drilling rigs have been added since that nadir. Of this total, about 35% have been added in low BTU plays (shown in red), while 65% have been added in high BTU gas and crude oil plays (shown in green), most of which are well within the Liquids Fairway.

Note that the Marcellus rig additions are shown in red, since most additions since mid-2009 have been made in the lower BTU region of northeastern Pennsylvania.

The NGL Value Chain Gauntlet

Even though a successful well in a high-BTU gas play provides the potential for a higher netback and corresponding revenues, it does not ensure those benefits. To realize those returns, a producer must run the NGL Value Chain Gauntlet.

In other words, although the pricing environment may be attractive, many other elements need to be in place to translate potential proceeds into actual revenues. These elements include:

- Access to processing: A processing plant with available capacity must be relatively nearby to the drilling location in order to extract the liquids and yield marketable, pipeline specification natural gas.

- Available transportation: Liquids need available transportation to market. This can be via truck or rail cars, but these tend to be expensive and labor intensive. The best alternative is an NGL pipeline, but if pipeline capacity is not available it can take years to develop and construct new capacity.

- Access to fractionation: The liquids are split or fractionated into their component parts (ethane, propane, butanes, and natural gasoline) at a fractionation plant. Most fractionation is performed at the central processing locations in Mont Belvieu or Conway, Kan. Fractionators have limited space. Currently many fractionators operating in the US are at or near full capacity.

- Market demand: A market has to be found for NGL products. NGLs are used as a feedstock for chemicals, plastics, motor gasoline, home heating, and several other markets. If these markets are oversupplied, prices will fall. Furthermore, if low demand or over-supply cause NGL prices to fall below parity with natural gas (and this typically happens with low ethane prices) processors will reject ethane, throwing that natural gas supply back into the market.

NGL production growth

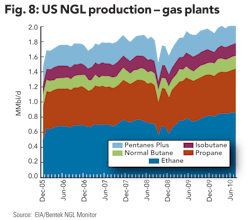

Consideration of the NGL Value Chain Gauntlet described previously is always important for gas producers in high-BTU plays. The level of concern about capacity and market constraints grows when NGL production increases. Such increases are happening today. Over the past three years, the rate of NGL production growth from natural gas processing plants has been accelerating (see Figure 8) and is now just above 2,000,000 Bbls/day.

Figure 8 indicates that US NGL production has been increasing since December 2005 at a CAGR (compound average growth rate) of 7.7%. That rate increased to 12.3% CAGR since early 2009 (following recovery from damage incurred during hurricanes Ike and Gustav in 2008). During the same period, the growth rate for natural gas production is only up 3% CAGR over the same period.

There are two primary reasons why NGL production is increasing at a much higher rate than natural gas production, both related to the Rush to Liquids. First, the higher value for liquids has resulted in more gas being processed to extract liquids. Second, new high-BTU gas development frequently requires new gas plants or upgrades to existing plants.

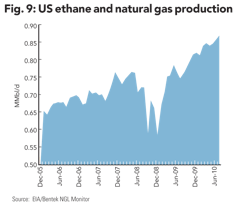

Most of the new plant construction uses cryogenic technology. A cryogenic facility can extract a much greater percentage of ethane from the natural gas stream. This greater ethane yield increases the total volume of ethane produced.

This implies that the most significant NGL production growth has been in ethane volume, and an examination of the data confirms that expectation. As shown in Figure 9, ethane production from natural gas processing plants increased by 200,000 bbls/day since December 2005, with 100,000 bbls/day increase occurring since early 2009. Ethane production grew at 19.2% CAGR over the past 18 months while, as noted above, natural gas was up only 3.0% during the same period.

Fractionation capacity

With NGL production on the rise and the utilization rate of many fractionators near capacity, there is some concern that fractionator constraints could limit further NGL production growth. In certain plays, such constraints are already impacting producers.

There are 36 major commercial fractionation facilities in the US. The largest fractionation centers are the Texas Gulf Coast region, (in and around the Mont Belvieu trading hub), the Louisiana Gulf Coast, and the Kansas/Oklahoma region. Total fractionation capacity is about 2.3 million b/d.

On paper, with NGL production of 2 million barrels/day and capacity of 2.3 million barrels/day, there should be adequate capacity to meet NGL producer requirements. However, the reality is different for three reasons.

- First, fractionation capacity may not be economically accessible. Several of the new shale plays do not have convenient pipeline access to processing plants with pipeline capacity to major fractionation facilities (such as in the Marcellus), limiting NGL output to mixed product (a.k.a. "Y-grade") that can be moved by truck or rail.

- Second, the only fractionation capacity that is economically accessible may be fully utilized (such as some portions of western Oklahoma).

- Third, some fractionators may not have capacity to meet the needs of the higher ethane production volumes. For example, if a fractionation plant has a 100,000 barrels/day nameplate capacity, this does not mean the plant is able to process a liquids stream containing 100% ethane, or 100% propane and butane. Fractionation capacity is optimized for a "normal" product mix. Higher concentrations of one product (such as ethane) cannot necessarily be accommodated.

Fortunately additional fractionation capacity is coming online. In Mont Belvieu, Targa is expanding its Cedar Bayou fractionation plant by 60,000 bblss/day in 2011. Enterprise is increasing capacity by 75,000 bbls/day at its Mont Belvieu plant in 2011 and has announced another 60,000 bbls/day in 2012. Enterprise is also expanding fractionation at two plants in the Eagle Ford natural gas basin at Shoup (from 69,000 barrels/day to 77,000 barrels/day in Q2 2011) and Armstrong (from 17,000 barrels/day to 20,000 barrels/day in Q4 2011).

Although several regional bottlenecks will exist due mostly to logistical situations, this additional NGL fractionation capacity will be adequate to meet the needs for most NGL producers over the next few years. The greater challenge will be to find a market for the growing NGL production.

Market demand for NGL production

There are three primary markets for NGLs: Petrochemicals, residential/commercial heating (that also includes your home barbecue grill), and the refining/blending market — which uses butanes and natural gasoline to produce motor gasoline. Each NGL product has a unique market profile. Almost all ethane production is used in the petrochemical market as a feedstock to produce ethylene, propylene, and other building-block chemicals. Propane moves into both the petrochemical and heating market. Some propane is also exported to Mexico and offshore markets, mostly in Latin America. Butanes and natural gasoline (a.k.a C5+) move into petrochemicals, motor gasoline, and export markets.

In total, about 30% of total NGL supply goes into the heating market, almost all of which is propane. Demand in the heating market is weather dependent — highly sensitive to cold weather in areas of the country that use significant levels of propane for home heating.

About 15% moves into the refining and blending market, which is most of the butanes and natural gasoline. The demand for NGLs from the refining sector is dependent on NGL prices relative to other gasoline components, seasonal shifts in the specifications for those requirements, and the general health of the motor fuel market.

The largest demand sector for NGLs is the petrochemical market, which absorbs about 55% of total NGL production. There are 27 major petrochemical facilities in the US, some of which have multiple units at the same location. These plants are called Olefin Units, Steam Crackers, or Ethylene Crackers, and are mostly located along the Texas/Louisiana Gulf Coast.

The demand for NGLs by the petrochemical sector fluctuates with the downstream demand for petrochemicals (influenced by economic activity, exchange rates, etc.) and the relative prices of NGLs to other petrochemical feedstocks.

To some extent, the petrochemical market acts as a balancing mechanism or "governor" of NGL demand. For example, if cold weather drives propane prices high, petrochemical plants will shift to lower price alternative feedstocks, reducing the demand for propane in the petrochemical market. Similar balancing mechanisms work for butanes and natural gasoline in both the petrochemical and refining/blending market.

The exception is ethane. Almost 100% of ethane is used in the petrochemical market, and thus the demand for the ethane component of the NGL stream is highly dependent on the petrochemical market. If downstream demand constraints for increased NGL production develop, the problem will most likely be concentrated in the ethane market.

The ethane market

Over the past year, about 80% of all U.S. ethylene cracker feedstocks were NGLs, with the remainder mostly naphthas and gas oils sourced from refinery output streams. Due primarily to attractive NGL pricing relative to the refinery streams, the feedstock percentage from NGLs has been increasing, with ethane taking a disproportionate share of the total. Most US ethylene crackers have been running maximum ethane volumes.

There are two reasons for this development. First, the growth in ethane supply has driven ethane prices lower relative to other feedstocks. This makes ethane the most attractive feedstock for these plants. Second, access to lower price ethane has been an advantage for US ethylene crackers in the global petrochemical market. Competing European plants rely more heavily on naphtha and gasoil feedstocks, which are more closely correlated to crude oil prices and thus are relatively more expensive.

With most ethylene crackers running maximum ethane volumes, the ability of the industry to absorb increasing volumes of ethane production is limited. Today the US ethylene industry can process about 950,000 bbls/day of ethane with almost all of that feedstock volume coming from natural gas processing plants. Capacity expansions are possible, and a few projects are being considered by olefins producers.

Whether these expansions will keep up with growing ethane production is an open question. The concern for the NGL marketplace is that continued increases in NGL production could create a situation where there is not enough petrochemical capacity to absorb all the ethane that NGL fractionation plants produce.

If ethane supply exceeds that capacity, ethane prices will be under even greater downward pressure. Declining ethane prices would impact economics of extracting ethane at gas processing plants, and shrinking the value of the NGL Producer Credit for natural gas producers.

Self-correcting mechanism: ethane rejection

There is, however, a self-correcting mechanism in the ethane market. If ethane prices drop below the price of natural gas on a BTU basis, a significant number of natural gas processing plants have the option to reject ethane — that is, to extract propane, butanes, and natural gasoline, but to leave some portion of the ethane in the natural gas stream.

How much ethane can get rejected is dependent on natural gas pipeline specifications, ability of the plant to make the ethane 'cut' without also rejecting propane and other liquids, and other factors.

When a substantial number of natural gas processing plants go on rejection, there are two market implications:

- Ethane production declines, ethane prices rise, and petrochemical demand falls, thus correcting the supply/demand imbalance.

- Natural gas plant output of natural gas increases, as volumes previously sold as ethane are sold in the natural gas stream.

The effects of ethane rejection on natural gas supply/demand balances are complex, depending upon physical plant capabilities, pipeline transportation and fractionation constraints, petrochemical market factors, and the pricing relationships between natural gas, NGLs, and alternative petrochemical feedstocks.

From an overall market perspective, it would be unlikely that ethane rejection could have a significant impact on natural gas supply. However, on a localized or regional basis, ethane rejection could increase natural gas supplies beyond gathering and pipeline transportation capacity, which could depress local prices and limit local production.

About the author

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com