Prepare now for regulation of OTC derivatives

Moazzam Khoja,SunGard Energy Commodities, Houston

In 1998, when Brooksley Born was chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), she tried unsuccessfully to bring transparency to the over-the-counter (OTC) derivative markets. Her efforts led to a strong negative reaction from Alan Greenspan, then chairman of the Federal Reserve, and administration officials who did not think that the status quo in OTC derivatives markets at that time posed significant danger.

Now, more than a decade later, the US Congress is engaged in overhauling the entire financial system in order to cope with future financial crises. Much has been written on the causes of the 2008 crisis, but at a very fundamental level it was caused by a highly leveraged system that did not have enough cushion to absorb the shock of unusual events. High leverage in a financial market is akin to tight supply in commodity markets as a catalyst for crisis.

For example, Midwest power prices spiked unusually high in 1988, due to tight power supply and above normal temperature. A similar situation occurred in 1997 with the natural gas basis market in Chicago.

The primary purpose of the legislation before Congress today is to increase transparency and reduce leverage. Although the proposed financial regulation is very comprehensive, this article will focus on Title VII, which regulates the OTC derivatives market by amending the Commodity Exchange Act and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

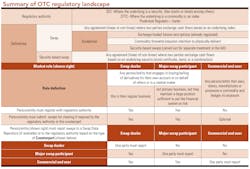

A key element of the bill is defining those terms that it then uses to establish regulatory authority and requirements. The bill defines OTC derivatives as various types of swaps, and classifies firms that trade swaps by their role as swap dealer, major swap participant, or commercial end-user.

Swaps

Swaps are defined very broadly to include any transaction where two parties enter into an agreement where value is derived by a security or an index, with a few possible exceptions. The exceptions include exchange of cash flows for physical delivery, exchange-traded futures, and certain security-based contracts described in the Securities Exchange Act.

Security-based swaps are carved out of the definition of swaps. These are derivatives where the underlying is a security (stock certificate, bond, or a combination). Security-based swaps are regulated by the SEC; most other swaps are regulated by the CFTC; these activities in banks may be regulated in part by their prudential regulator.

Cleared swaps are those that are subject to clearing requirements.

Photo courtesy of SunGard Energy Commodities.

The term "swap" does not discriminate between linear and non-linear instruments, making all types of options and exotic structures qualify as a "swap" under this definition. The purpose behind the broad definition is to help ensure that few instruments can escape regulatory scrutiny and transparency.

Swap market roles

A swap dealer is one who engages in the buying and selling of swaps, either for his own account or on behalf of someone as a regular business or who is a market maker.

The major swap participant is someone who may not be a dealer, but who keeps a substantially large open position not related to hedging that creates substantial credit risk.

In essence, such an organization may have similar obligations as a swap dealer even though it may not be their principal business. The defining characteristic is whether their swap activity can cause systemic risk to the financial system.

A commercial end-user is broadly defined as an entity that uses, stores, and processes commodities (extensively defined), and only uses the swap to hedge its risk.

These definitions are activity based. Part of an entity can be a swap dealer and another part can be a commercial end-user, depending on their respective activity

Swap market regulation

Swap dealers and major swap participants have an onus to register and be subject to clearing or margin requirement or be subject to capital requirements. The bill further mandates that major swap participants and swap dealers clear most swaps through a centralized derivative clearing organization (DCO) and be subject to daily margining by the DCO.

Cleared swaps must also be executed in either a board of trade or a registered swap execution facility to help ensure market transparency.

The burden is on the regulators to make rules that define which swaps are subject to clearing. The bill defines criteria to make this determination on swaps offered for clearing. There are many factors that the CFTC should consider; including standardization of the contract, availability of prices, and volume.

The intent is that only highly customized or illiquid swaps or those that are not accepted by any DCO would not require clearing by major swap participants and swap dealers. These would instead be subject to capital requirements.

However, to the extent at least one entity in a swap transaction acts as a commercial end-user, the swap would not be required to be cleared with a DCO and would not be subject to margin or capital requirements, although a commercial end-user may elect to clear the swap voluntarily.

Since transparency is a key goal of the bill, it contains a mandatory public reporting requirement for all swaps. Cleared swaps are subject to real-time public reporting by the DCOs.

Real-time means "as soon as technically practicable after execution." Otherwise, the bill requires timely reporting to a new entity known as a "Swap Data Repository" or, if not accepted by such, then directly to the applicable regulatory body. The purpose is so that regulators can have complete transparency into these markets.

Regulatory effects

If this bill becomes law, the resulting financial regulation will impose certain challenges for companies engaged in swaps. Under current versions of bills passed by both chambers of Congress, the business practice for "commercial end-users" will not substantially change, other than the obligation to demonstrate that their trades are hedges.

Congress left it up to the regulators to further define commercial hedging activity via rulemaking, so it is still possible that there will be documentation requirements. It is hoped that regulators will interpret commercial hedging to refer to economic hedges, rather than accounting hedges.

If two commercial end-users trade with each other and elect not to clear the trade, one of them would report it to a Swap Data Repository. Otherwise, this responsibility would belong to the swap dealer or major swap participant with which they trade.

The exception that absolves end-users from margining and capital requirements for their hedging activity was a contentious issue. Forcing end-users to clear contracts and subject themselves to the margining could have become counterproductive if they decided to avoid hedging altogether. This would not be a prudent consequence of this regulation.

In both versions of the bill, this problem was properly addressed and mitigated. For swap dealers/major swap participants, the proposed legislation would impose many obligations. First, they need to register. Second, they would need to clear where clearing is required or report trades when clearing is not required. Finally, they could be subjected to capital requirements.

The purpose of this requirement is to ensure that adequate capital is allocated for swap activity. This is important for the stability of the system.

Two benefits occur because of margining and capital requirements. Margining imposes a self discipline. It is human nature to not worry about things until they become due. Initial margining requires setting aside part of the at-risk funds in advance of the outcomes, while variation margin imposes a daily settlement process that forces organizations to actively view risk. Imposing capital requirements will ensure that swap participants allocate enough risk capital for the risk taken by engaging in complex or customized derivative activity that cannot be cleared.

Any system that does not have redundancy causes shocks. Just like excess supply or redundancy can stave off a power or natural gas price spike, regulatory capital and reduced leverage can stabilize financial markets.

Conclusion

The pending financial regulation of OTC derivatives is a largely well thought out and balanced approach to enforce stability through margining and capital requirements. While not finalized, the proposed legislations makes huge shifts, and companies of all types involved in commodity markets need to begin preparing by making the requisite investments in people, process, and technology.

It is to be hoped that the exceptions for legitimate end-users will stand, so that they are not unduly burdened by the margin requirement and discouraged from hedging. The capital and margin requirements are two potent tools in the hands of the regulators who can use them to create a financial cushion to avoid potential destabilizing events. The key questions are: 1) Will organizations be equipped to deal with the additional reporting and risk management requirements?; and 2) Will regulatory agencies be given sufficient resources to obtain additional staff and systems necessary to handle the additional workload? Only time will tell.

About the author

Moazzam Khoja, CFA, is senior vice president of SunGard Energy and Commodities Inc. He joined SunGard in 2004 and he is actively engaged in the strategic development of the firm's software solutions. He has spent the past 14 years dealing with energy and commodities derivatives, focused on software strategy, risk management, pricing and valuations of energy and commodity derivatives structures, and research. He has authored many articles and spoken in many forums on topics relating to managing commodity risk in speculative operations, optimizing hedging decisions, and valuing and pricing complex energy and commodities derivatives. Khoja received his MBA from the Columbia Business School in 1996 and obtained his CFA charter in 2003.

Acknowledgement: David Benepe of SunGard Energy and Commodities for his research and contribution to this article.

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com