Considering CapEx investments in a time of unusual uncertainty

Richard Westney, Westney Consulting Group, Houston

Confidence in traditional measures of investment risk and return continues to erode. This is not surprising. In his recent testimony before Congress, Ben Bernanke stated, "We recognize that the economic outlook remains unusually uncertain." According to Mohamed El-Erian (CEO of Pimco), writing in the Financial Times, this heightened uncertainty is already changing the way we think about investment decision-making. None of this is news to investors in general or to those who are responsible for investing in major capital projects.

Unusual times call for unusual measures; uncertain times call for measures of uncertainty

Every decision-maker yearns for predictability, and this is especially true today. To predict is "to make known in advance" and investors in capital-intensive organizations or specific projects have long held the expectation that the developers and engineers proposing projects will be able to make known in advance the cost and time to complete with sufficient accuracy for a responsible investment decision.

But what does an investment decision-maker do if the level of risk associated with a project's size, duration, technology, location, and prevailing economic conditions make the required predictability impossible to achieve?

Interestingly, a synonym for predictability ("the quality of being predictable") is banality (to be "drearily commonplace"). Surely we would not complain if predictable project outcomes were "drearily commonplace." But, as we have seen, predictable outcomes are far from commonplace — in fact the reverse is true.

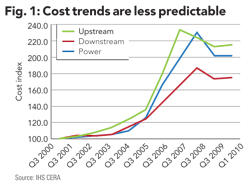

What assumptions should decision-makers make today about the cost of a project in which they intend to invest and which is to be completed five years from now? An investor might examine historical cost trends and find that, after a long period of price stability, in 2005 the cost of capital project goods and services took a sudden and unanticipated upward turn as seen in Figure 1.

These unprecedented cost trends, along with other unfortunate lessons from the financial crisis, are good examples of the inadequacy of historical data as a means to gain confidence in forecasts. Not only is the future direction of project costs unclear, significant volatility must also be accounted for.

Clearly, when it comes to investing in capital projects, these are truly uncertain times. As a result, our cherished notions that capital projects are predictable must be replaced with a hard-nosed, reality-based approach that addresses head-on the challenge of ensuring our project investments will deliver the outcomes we expect.

If we can't have predictability, can we at least have the ability to manage it?

Of course there are well-established conventional practices to help ensure project predictability. Private equity and other project investors often look for a management team with a strong record to bring effective risk management to bear.

These managers often implement a phased and gated project development process to ensure that sufficient "front-end loading" has been done such that the project's scope and planning are well defined when the final investment decision is made. Of course this best practice makes a lot of sense but, since there are important risks that are not reduced by improved project definition, even projects that have been led by experts who invested considerable time and effort in front end definition have gone on to become "train-wrecks."

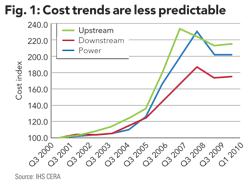

The assumption that current best practices will give us the predictability we need must be replaced with a fresh approach that recognizes capital predictability, not as a problem to be solved, but instead as a variable to be continuously managed. This process of continuously managing predictability is illustrated by the diagram shown in Figure 2.

The key to managing predictability is calibration. We must first understand the drivers of risk and uncertainty if we are to be able to develop de-risking strategies. Ongoing attention to these strategies enables preservation of the predictability we have achieved, as does periodic re-calibration that renews the process. Calibrating a project's predictability requires some fresh thinking and is therefore the focus of this article.

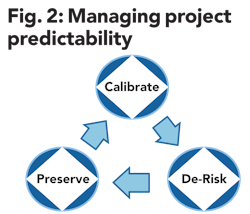

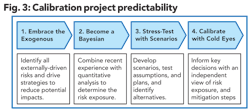

Calibrating project predictability requires a four-step process as illustrated in Figure 3.

Step 1: Embrace the exogenous

The conventional approach to project risk management tends, naturally enough, to focus on those risks that engineers and project managers can control. These are typically the risks associated with the tactics of engineering, procurement, and construction.

Diligent application of project management best practices such as adherence to a gated process and diligent completion of "Front End Loading" (FEL) can significantly reduce both the probability and impact of these risks. Contingency funds are added to the cost impact to cover their impact.

However, this approach often ignores or minimizes exogenous risks: those risks that are largely driven by external forces over which we have little or no control. Major, international projects encounter many such risks; in fact they are usually the cause of the large cost overruns and schedule delays that so often occur. These risks typically include:

- Geopolitical conditions and trends

- Global and regional economic conditions

- Influence of non-financial stakeholders such as non-government organizations (NGOs)

Embracing the exogenous means taking an early, focused approach to identifying all such risks, understanding their causes and effects, and developing proactive management strategies to address them.

Step 2: Become a Bayesian

Most investment decision-makers have access to the skills of risk analysis professionals, and the results of their probabilistic analysis of a project's cost, duration or economic value. The role such analyses should play in decision-making has long been debated and, as a result of the financial crisis, this debate has only intensified.

Risk analysis attempts to predict future outcomes in one of two ways: it can look backward by performing statistical analysis of past data, or it can look forward and simulate the range of possible outcomes for the project at hand and the environment in which it will take place. In either case, the question is the extent to which the results of quantitative analysis should be tempered by judgment.

Bayesian thinking approaches this issue by acknowledging the importance of judgment in performing probability analysis, with particular emphasis on incorporating recent data and trends. Clearly, a traditional, backward-looking analysis in 2005 would have missed the dramatic cost trends that were already evident at that time (see Figure 1). Bayesians at the time were looking at the earlier indicators of these trends, and incorporating these into their analyses of risk exposure.

Step 3: Stress-test with scenarios

One of the problems decision-makers have with incorporating the results of risk analysis into their decision process is that risks do not occur one-at-a-time. So sensitivity studies (e.g., what happens if this risk should occur?) that assume all other risks are frozen are of questionable utility.

Scenarios provide a composite view of how several risk drivers might interact and how this might impact the project. They provide an excellent tool for stress testing assumptions, strategies, organizational capabilities, and execution plans. The result may be minor adjustments, contingency plans, or an increased vigilance over the indicators of the potential severity of key risks.

Step 4: Calibrate with cold eyes

Of all the explanations routinely offered for cost overruns, perhaps the one that hits the target most cleanly has been offered by Bent Flyvbjerg based on his seminal research on mega-projects: it is not so much that projects cost more than they should, it is that they were severely underestimated in the first place.

Why does this happen? Most organizations rely on their internal processes to ensure that a project is ready for the final investment decision and all risks have been identified and understood. And, internal processes inevitably have systemic sources of optimism as a result of rational economic behavior by project sponsors that encourages optimistic assumptions and unrealistically low cost estimates.

Independent, cold-eyes reviews can overcome this inherent internal bias by examining all aspects of the project's value proposition — commercial, financial, technical, and execution. The review team can review each of these project dimensions from the perspective of both risk (ensuring we fully understand all the risks involved and have addressed them appropriately) and readiness (verifying that all the work that should have been done at this point has in fact been done properly). This calibration of the project's status provides the understanding of the predictability of the project's outcomes that is needed to make a risk-informed investment decision.

Summary

Investors in capital projects or capital-intensive industries today find themselves on the horns of a dilemma: on the one hand, boards of directors and executive committees are demanding more effective risk management and more predictable results; on the other, the outcomes of major capital projects are more unpredictable than ever.

The conventional wisdom that if you do enough engineering and have an experienced management team your major risks have been mitigated is simply insufficient today. Decision-makers need a more complete understanding of all project risks and what needs to be done to manage them.

By facing up to the inherent unpredictability of project outcomes, and applying the four-step process for calibrating predictability, we can be in a position to de-risk our projects, improve predictability, and gain the confidence needed to move forward.

About the author

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com