Hydraulic fracturing: The regulatory year in review

Robert Earle, Analysis Group, San Francisco

One year ago, hydraulic fracturing was just starting to become a part of the general public consciousness. Gasland had come out and was playing on HBO in June 2010. As anyone in the industry who has suffered through watching the film knows, fracturing has become the byword for both shale gas development, in particular, and natural gas development, in general.

Shale gas has been a boon for the US economy and consumers, even as increased public and government scrutiny has heightened the risks for developers and investors. For example, Legacy Resources, an oil and gas exploration company based in Texas, recently backed out of a $45 million deal to buy a shale gas field in Wyoming after the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) said it had found levels of benzene at the site that were 50 times above those considered safe for humans.

Combined with horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing has greatly increased the amount of economically recoverable gas in the United States. However, issues that can occur when any well is drilled-for instance, whether proper casing techniques have been followed or whether excessive levels of methane are being emitted-often get lumped into the category of fracturing-related issues, simply because so much of the current boom in natural gas development involves hydraulic fracturing. As a result, many issues are linked in the public mind to hydraulic fracturing when strictly speaking, they are not directly connected.

For instance, methane intrusion into ground water is often linked to the practice of hydraulic fracturing. Methane, of course, exists naturally in many groundwater supplies. When methane intrusion does occur because of natural gas development, it is usually because of failures in well casings. These incidents, however, often get blamed on hydraulic fracturing.

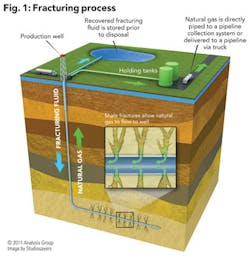

Strictly speaking, hydraulic fracturing involves the injection of water, which has been mixed with a substance such as sand and a small amount of chemicals, into a shale formation in order to release natural gas or oil from it. And, the best evidence we currently have shows that hydraulic fracturing in itself does not cause methane intrusion.

At the national level, there has been much activity concerning hydraulic fracturing. The EPA has launched several investigations, and Secretary of Energy Steven Chu asked the National Petroleum Council (NPC), an advisory group to the secretary, to produce a report on North American resource development. The report, released in September 2011, reflects input from a range of industry experts, environmentalists, and academics. It addresses many issues beyond hydraulic fracturing and contains detailed information about shale gas development that has not been compiled elsewhere. Dr. Chu also asked his Science Advisory Board (SAB) to look at the issue of shale gas development. Like the report by the NPC, the SAB's final report, which was issued in November 2011, calls for better regulation on the federal and state levels, as well as efforts by industry to improve standards and sharing of knowledge around environmental safety.

These calls for increased industry responsibility are a first step toward preserving the benefits from increased production of natural gas and reacting to the flood of shale-gas-related activity that is happening on state and local levels. In the past year, for instance, the oil and gas industry has launched FracFocus, a voluntary registry of the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing. Participation in FracFocus has been widespread although not universal. Under federal law, companies are exempt from disclosing the chemicals they use in hydraulic fracturing, so many both inside the oil and gas industry and those outside it support state regulations that would mandate participation in FracFocus or a state-established registry.

Texas, California, Wyoming, Pennsylvania, Arkansas, Michigan, and Colorado have already enacted or are considering enacting laws that would require the disclosure of fracturing fluids. These disclosure initiatives differ on a number of points, including whether the volume of water and chemicals must be disclosed, whether the information is made public, and whether some information can be withheld as a trade secret.

This last issue is especially contentious. Hydraulic fracturing experts say that each play requires the development of a specific formula for the fracturing fluids. Therefore, the disclosure of these inputs could result in the loss of valuable intellectual property, they say. Meanwhile, some environmentalists fear that companies' ability to withhold information because of IP concerns would allow them to hide their use of chemicals that may be harmful to the environment.

Potential investors in shale gas production in a state should ask themselves the following questions about disclosure issues:

- To what degree is the formula that works well in the play already known, or does venture possess intellectual property that gives it an advantage?

- If there are disclosure requirements, are there exclusions for trade secrets or intellectual property?

- If there are no exclusions for intellectual property, are the disclosures made public?

- If they are made public, what is the time frame and what is the specificity of information?

- For instance, do exact volumes and formulae need to be disclosed?

The answer to each of these questions will affect the valuation, and risk, associated with a particular deal.

In addition to disclosure-related legislation, there has been much activity on general regulation of natural gas development on the state and regional levels. The oil and gas industry seems to be of two minds on these developments. Some perceive potential regulation as unnecessary interference in productive business activities. Others believe that without a clear regulatory framework in place, with competent and adequately funded regulators to implement laws, accidents will happen and a few incompetent operators will ruin the development opportunity for all producers. Moreover, some hope that the establishment of clear and reasonable regulations would provide a safe harbor for investors, so if there are problems liability would not be unlimited.

Key states with legislative and regulatory actions:

- The New York Moratorium for drilling in the Marcellus Shale was issued in December 2010 and was partially lifted earlier this year despite an attempt in the legislature to continue the moratorium until June 2012. Further environmental review was conducted with a revised impact statement issued and public comments accepted until Dec. 12, 2011.

- In New Jersey, a bill passed in the legislature would have permanently banned fracturing in the state but was vetoed by Governor Chris Christie, who proposed a one-year moratorium. This moratorium was derided by the Sierra Club, because no gas companies have immediate plans to drill in New Jersey.

- West Virginia established an emergency rule to address horizontal drilling and fracturing practices. The rule included requirements for shale gas well operators to provide erosion and sediment control plans as well as site safety plans. If a large volume of water was to be used, water management plans were required as well.

- The multi-state Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC), covering Pennsylvania, New York, and Delaware, regulates water quality protection, water supply allocation, regulatory permitting, and water conservation initiatives for the Delaware River Basin. Over a third of the basin is on top of the Marcellus Shale. In May 2009, the DRBC announced that natural gas extraction projects located within the drainage area of the Basin's Special Protection Waters must be approved by the DRBC. A final draft of regulations was released on Nov. 8, 2011, but the final vote for approval has been postponed.

- The Ohio EPA released a draft general air permit regulation for shale gas production in October 2011.

Finally, in addition to legislative activities, there have been some notable enforcement activities that deserve investors' attention. Any regulatory regime may create risks, but investors should consider whether the lack of such a regime and the use of other enforcement mechanisms, such as the courts, would be a preferable option. On the federal level, the EPA has made it clear that while it lacks explicit authority to regulate fracturing under the Safe Drinking Water Act, it will attempt to achieve effective regulation by using its enforcement authority under other statutes.

For instance, late in 2010 the EPA issued an emergency administrative order that required Range Resources Corporation, an independent oil and gas producer operating in several shale formations, to provide drinking water, stop migration of methane, remediate affected groundwater, and conduct monitoring in relation to claims of well-water contamination in Parker County, Texas.

This enforcement action has been stayed, pending review by the courts. While federal action on Range Resources may still happen, it is interesting to note that recent proceedings at the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates the oil and gas industry in that state, concluded that Range's natural gas drilling activities did not contribute to the contamination.

Pennsylvania is also notable for its actions against two companies drilling in the Marcellus Shale region- Cabot Oil & Gas Corporation for methane contamination and Chesapeake Energy for contamination of private water supplies. In particular, the well failures associated with Chesapeake Energy prompted activity by the state of Maryland, with an intent to sue notice, and by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection.

In addition to these governmental enforcement actions, there is pending private litigation in Arkansas, Colorado, Louisiana, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, and West Virginia. As these private suits move forward, investors will need to consider which jurisdictions prove riskier than others, whether the United States is moving toward federal primacy and away from state dominance of the regulation of gas production, and which methods can mitigate regulatory and litigation risks going forward. OGFJ

About the author

Robert Earle, vice president at Analysis Group, has extensive experience in the energy industry, including natural gas markets, resource planning, tariff design, risk analysis, and valuation. He focuses much of his work on analyzing market opportunities, strategy, regulatory issues, and litigation related to the oil and gas sectors. Earle previously was manager of economic analysis at the California Power Exchange where his responsibilities included developing an overall analytic infrastructure for market analysis, analysis of new products, and briefing regulatory and legislative bodies.

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com