Comparison of project structures in an LNG liquefaction plant

Thomas E. Holmberg, Baker Botts LLP, Washington, DC

Photo courtesy of Sempra Energy.

A fundamental decision that project participants must make when developing a liquefied natural gas (LNG) infrastructure project is how to structure the project. The structure of a project will affect the risk profile of the project and, as a consequence, the type of financing the project will attract and the ease with which the project may be financed.

The final structure elected by the project sponsors will, of course, also depend on various other factors, including the existing contractual relationship among the project sponsors, and local law and tax regimes. This article compares the three following project structures for LNG liquefaction projects:

- an integrated project model in which the participants share a unity of interest in the LNG value chain from production of natural gas through the liquefaction of the LNG;

- a project company (or merchant) model in which the project company that owns the liquefaction facility purchases natural gas as feedstock from a seller (or sellers) and resells LNG to offtakers; and

- a tolling model in which the LNG plant does not take title to natural gas feedstock or LNG produced at the plant, but provides liquefaction and processing for the owners of the feedstock natural gas.

Summary of project models:

Integrated project model

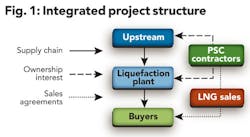

In an integrated project, one or more investors own rights to natural gas reserves. Where there is more than one investor, they share the production of the reserves pursuant to a Production Sharing Contract (PSC) or similar agreement. The parties to the PSC (the PSC Contractors) build the necessary infrastructure to monetize gas reserves, and the LNG plant is one part of the integrated project necessary to produce the natural gas, liquefy it, and market the resulting LNG. Each PSC Contractor holds an undivided interest in the LNG plant in proportion to its ownership of the rest of the project.

Figure 1 shows a typical integrated project structure.

Typically, each PSC Contractor holds title to its share of LNG production from the time natural gas is produced from the field until the sale of LNG to a third party. Sales of LNG may occur at the tailgate of the LNG plant (in the case of a CIF or FOB sale), or at a receiving terminal (in the case of a DAP sale). Under an integrated project structure, the equity owners may or may not act in unison to sell volumes of LNG from the LNG plant.

If the PSC contractors have the necessary capital to construct the project, an integrated structure has many benefits. These benefits include alignment of interest among the PSC contractors and the ability to share costs across the entire LNG supply chain, which may be beneficial for tax reasons and cost accounting reasons (for example, the PSC Contractors may want to use the early losses from construction of an LNG plant to offset profits from any natural gas liquids production, thereby possibly reducing the PSC Contractors' royalty or tax obligations).

In addition, in an integrated project, each natural gas supplier (who is also a PSC Contractor) has control over its own production and is in a better position take advantage of market opportunities than it would be if the supplier were bound by a long-term gas supply agreement with a separate LNG plant company (subject, of course, to any minimum deliverability obligations).

Project company (or merchant) model

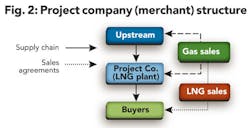

Under a project company model, the company that owns the LNG facility (Project Co.), unlike the PSC Contractors described above, does not have an interest in the upstream assets. Instead, Project Co. owns the LNG plant. Project Co. purchases natural gas as feedstock for the plant, processes that natural gas into LNG, and sells the LNG to one or more buyers on an FOB, CIF, or DAP basis for Project Co.'s own account.

There are many variations of the project company model. In some cases, the entities that own Project Co. will also own the upstream facilities. In other cases, there is not a unity of interest along the LNG supply chain. For example, a project may be structured so that, although the natural gas supplier(s) are not identical to the group that owns Project Co., most of the owners of the upstream natural gas supplies are owners of the LNG liquefaction facility.

In yet another variation, a governmental entity may own Project Co. (directly or through the state-owned national oil company), while an operating company owned by the upstream PSC contractors (e.g., in proportions that are substantially similar to their ownership of the upstream supplies) operates the facility.

Figure 2 shows a typical Project Co. (merchant) project structure.

There may be several reasons for structuring Project Co. as a separate company even where there is a unity of interests in the LNG supply chain. For example, tax considerations may require a distinct company with separate profit (or loss) from its operations, or local law may require the LNG facility to be owned by a governmental entity.

Commercial considerations may also dictate the use of a project company model. If the upstream owners are unable (or unwilling) to invest in the liquefaction facility, a separate project company may be merited. In other cases, some owners of the plant may not have an interest in the upstream supplies, so an integrated project model will not be possible. The fiscal regime in the project country defining when the first commercial sale of hydrocarbons occurs may also influence the sponsors' selection of a project company model.

Although the project company model may be useful to address legal and commercial considerations, it does impose some risk on Project Co. Among the most significant of those is the commodity pricing risk that Project Co. takes in purchasing natural gas and selling LNG. For example, because LNG is sold by Project Co., which is a separate entity from the party that produced the natural gas, Project Co. must purchase natural gas from the upstream producers (or some intermediary party) pursuant to a gas supply agreement.

If the upstream suppliers are not owners of Project Co., negotiation of the gas supply agreement could prove more cumbersome, and an upstream supplier may force an undesirable allocation of market risks on Project Co. through the pricing mechanisms in the gas sales agreement. For example, the gas sales agreement may include a netback price based upon the sale price of LNG from the project or may include a participating economic interest in the revenues of Project Co.

The use of a project company model reduces somewhat the flexibility of each equity holder with respect to the production of natural gas and disposition of LNG, because all sales are made in unison through Project Co. However, making such sales on a unified basis simplifies issues related to the management and allocation of the capacity of the LNG plant. Even though the sales are made in unison, a variety of LNG sales arrangements are available. In most circumstances, Project Co. sells LNG to third parties under a long-term LNG sale and purchase agreement (SPA), with Project Co. taking the upside and downside commodity risks associated with buying natural gas and marketing LNG.

An alternative to this approach is for Project Co. to sell LNG on an FOB basis to the project sponsors, which are responsible for lifting and marketing LNG in proportion to their equity shares of Project Co. Depending on the pricing structure, such an arrangement could reduce volatility risk to Project Co., thereby enhancing the predictability of the revenue stream.

Tolling model

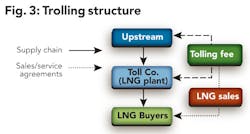

Under a tolling model, the company owning the LNG liquefaction facility (Toll Co.) does not take title to the natural gas that is processed. Instead, Toll Co. receives a fee (the Tolling Fee) to provide the service of processing natural gas owned by a producer or a purchaser of LNG.

Figure 3 shows a typical tolling structure.

Under a typical tolling structure, the owners of the natural gas sell their natural gas (as LNG) to a downstream buyer at the tailgate of the LNG plant. As with other project models, there are variations of the tolling structure. For example, in one possible arrangement, Toll Co., while still receiving the Tolling Fee, takes title to the LNG and is the FOB seller of the LNG. This hybrid arrangement, sometimes referred to as "quasi-tolling," allows Toll Co. to share in pricing upside while the Tolling Fee insulates Toll Co. from price risk.

As illustrated in Figure 3, a principal benefit of a tolling structure is the minimization of market risk to Toll Co. through the predictable payments of the Tolling Fee. A typical Tolling Fee structure is a two-part fee. The first part of the two-part fee is a reservation charge paid to ensure that the LNG plant has the necessary capacity to liquefy a natural gas owner's natural gas on a regular basis (e.g., monthly) and is payable whether or not any natural gas is actually liquefied. This reservation fee would allow Toll Co. to recover fixed costs, as well as a return on capital.

The second fee (e.g., a commodity charge) may be assessed per unit of natural gas processed. This fee would recover the variable costs associated with processing the natural gas. By structuring the Tolling Fee this way, Toll Co. minimizes its market risk (including price volatility), since the reservation charge is payable irrespective of whether any LNG has been produced or any sales of LNG have been made by the owner of the LNG to offtakers.

A tolling structure may be appropriate where there is uncertainty of natural gas supply or of downstream markets. In such a case, the upstream supplier may be willing to bear the risk by committing to the Tolling Fee in exchange for Toll Co.'s investment in the project. This would also be the case if the project sponsors wish to attract outside investors to the project.

A tolling structure may also be appropriate as an alternative to an integrated project if the project sponsors anticipate receiving supply from multiple fields or in circumstances where the local tax regime imposes taxes that could apply in the other structures (for example, a tax on title transfer). Finally, a tolling structure can facilitate project financing to the LNG plant since the project revenues are not directly exposed to market risks.

Conclusion

There is no "standard" structure for an LNG liquefaction project. Selecting a project structure depends on the identity of the project participants (throughout the value chain), tax and legal regimes, risk appetite, and financing considerations. Although the three basic structures discussed above provide a good starting point for considering and selecting a project structure, the possible number of variations is limitless, depending on factual circumstances – and the creativity of the project sponsors. OGFJ

About the author

In a "Cost, Insurance and Freight," or CIF sale, the seller delivers the goods to the buyer on board the vessel and risk of loss passes from the seller to the buyer on board the vessel. The seller is responsible for the costs and freight to bring the vessel to the port of destination and is also responsible for insurance to cover buyer's risk of loss to the goods. In a "Free on Board," or FOB sale, the buyer is responsible for providing LNG shipping, and title and risk of loss pass from the seller to the buyer as the LNG is loaded onto the LNG ship from the liquefaction facility. In a "delivered at place" or DAP sale, the seller is responsible, at its own expense, for providing shipping for the LNG, the title to and risk of loss of which transfer from the seller to the buyer as the LNG is unloaded from the LNG ship to the receiving terminal. |

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com