Would North Sea oil revenues fund an independent Scotland?

A large oil rig close to shore in Northern Scotland

Barney Gray, Old Park Lane Capital, London

Would an independent Scotland thrive on North Sea oil and gas revenues? Could an independent Scotland be economically viable without increasing tax or cutting services to an unacceptable degree? Would the Scottish be better or worse off outside the United Kingdom? These questions have become the subject of heated debate between the UK government and the Scottish National Party, with the SNP's opponents claiming that, even with North Sea oil and gas tax revenue, the English subsidize Scotland.

Following the resounding "no" in the referendum for a regional assembly in the North East in 2004, it is recognized that the specter of any increase in local taxation, or cutting public services, is a huge deterrent to electors voting for independence. The economic statistics therefore need to be looked at closely.

Frustratingly the "facts" quoted by each side often seem to conflict. I'm not an economist. However, one of the pillars of the economic argument put forward by the SNP hinges on the long-term value of oil and gas revenue from the North Sea. As such, the issue has become central to the viability of Scottish independence.

In an interview with The Economist published in January, SNP leader Alex Salmond claims that 90% of North Sea oil revenue belongs to an independent Scotland and that with this revenue, Scotland is in an economically stronger position than the rest of the UK. While the 90% figure would need to be negotiated with the Treasury in Whitehall, and I don't think they would get anywhere near that amount (see below). Using the 90% figure (SNP's best case) and keys such as the price of oil and expected production levels gives (in my opinion) a clear and authoritative picture of the economic reality of an independent Scotland.

It's worth first looking at the hard economic data to see why the North Sea revenues are so important. Scotland accounts for 8.4% of the UK population, 8.3% of the UK's economic output, and 8.3% of the UK non-oil tax revenues. However, Scotland accounts for 9.2% of total UK public spending.

Statistics from the Scottish Executive showed that in 2009-2010, the latest period for which figures are available, total public expenditure in Scotland was £59.2 billion (US$94.1 billion), equivalent to £11,370 (US$18,078) per person. This compared to the UK per capita total of £10,320 (US$16,409). Non oil-tax revenues in Scotland were £42.7 billion (US$67.9 billion) in the same period, which equates to £8,221 (US$13,071) per person – significantly less than public expenditure.

www.woodmac.com/northseamap2012

This argument is used to suggest that England is currently subsidizing Scotland, but that is disingenuous. The UK's total budget deficit equates to £2,000 (US$3,180) per head anyway, not a million miles away from the Scottish per capita deficit and London and the South East are effectively subsidizing the rest of the UK, including much of the rest of England. And of course, the UK Treasury is subsidized by the bond market to fund the deficit anyway.

To fund an independent Scotland, the SNP has based its economic arguments on the premise that the value of "North Sea oil and gas revenue" is as much as £13.4 billion (US$21.3 billion) per annum. However elsewhere they talk about "North Sea revenue" and "North Sea oil." It makes a huge difference which of these they're actually referring to. However, most commonly, such as in their manifesto, they refer to "North Sea oil and gas revenue" so the following is based on that interpretation.

Looking at the figures, I believe that the £13.4 billion per annum figure is based on an historical spike in North Sea revenues in 2008-2009 when oil prices exceeded $144 per barrel at one point. Using these figures, an independent Scotland, with 90% of those revenues (£11.7 billion, or US$18.6 billion), would have a budget deficit of only £4.8 billion (US$7.6 billion) – considerably smaller than the rest of the UK on a per capita basis. Aside from the fact that this calculation was derived from a highly convenient point in the cycle, I believe that the SNP's figures don't recognize a number of the harsh realities of the oil industry.

Oil prices are very volatile. Although the current Brent benchmarked oil price is in excess of $100 per barrel, the price fluctuated by more than $112 in 2009. The price is affected by global geopolitical issues beyond the control of Scotland. With one exception, North Sea revenue has shown a year on year decline every year since 2004-2005. The one exception in 2008-2009 was when oil prices hit unprecedented peaks in excess of $140 per barrel.

To get a true picture you need to look at more recent years such as 2009-2010 when North Sea revenue was just £6.5billion (US$10.3 billion). In reality, unless there is a sudden and unexpected rise in oil prices, tax revenues will therefore be far less than the SNP are assuming. Of course, the experts could be wrong and oil prices could start to increase again, but I think it unwise to base key economic decisions on prices going against the current trend.

The Scottish economy would also be disproportionately dependent on high oil prices. In the UK, a fall in oil prices is not ideal for public finances, but it is not a disaster (and of course it has its advantages!). In an independent Scotland, it could easily wipe 15% from the planned public expenditure budget. That sort of uncertainty would cause huge challenges, in planning, budgeting, and of course in proving to the banks that Scotland is a viable risk. The only way to manage an economy with such volatility at its core would be to have huge reserves to carry it through.

However, there is much worse news for the SNP. Oil production in the North Sea is also declining steadily. In 2012, it is likely to drop below 1 million barrels a day (not a million barrels a year as some national media quoted recently) from a peak of just under 3 million barrels a day in 1999. Unless concerted action is taken to stop or at least slow the decline, it is possible that at some time in the next 12 years, many of the largest producing oil fields will face abandonment.

To address this problem Scotland would have to start behaving like Norway, which actually considered the solution to the same problem some years ago. Scotland shares a number of similarities to Norway in terms of population and dependence on oil and gas revenues.

Norway, like the UK, imposes a very high tax burden on North Sea oil and gas production. In Norway the rate of tax is 78%, and in the UK it runs as high as 82%, depending on the age of the oil field. However, Norway recognized that this level of taxation was preventing companies from starting new exploration projects. As an incentive, the country introduced a tax rebate that amounts to a rebate on the exploration costs for companies when they found and developed hydrocarbons. This provides explorers with the means to raise development capital as the market then takes account of this additional return from the Norwegian exchequer.

The tax incentive has contributed to a considerably slower decline in North Sea production in Norway compared to the UK from similarly timed peak output, and after five years it paid for itself in tax revenues. However for those five years Norway had to sacrifice short-term revenue. Nevertheless, with its economy in a stronger position through the 1980s, Norway was able to build up a sovereign wealth fund of US$550 billion. To put the scale of this figure into context, it is the equivalent to more than three times the UK's forecast fiscal deficit in 2011-2012.

To be able to depend on North Sea revenue in the long term, Scotland would therefore need to sacrifice a large proportion of North Sea tax revenue for at least five years as it reorganizes its fiscal regime, while already running a sizable budget deficit.

At this point it is also worth looking at the arguments behind the SNP's claim for 90% of North Sea revenues. The BBC's Douglas Fraser recently said that Scotland could "expect to have more than 80% of the UK's oil and gas revenue." The SNP's opponents argue that England has a claim to between a quarter and a third of the North Sea oil and gas fields. Centrica, which owns British Gas, believes just 14% of North Sea oil and gas areas would fall in Scottish waters, saying that the rest is in the territory of England, Norway, and Holland.

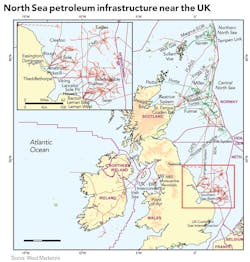

If you look at the maps there can be some argument over whether the maritime border should follow the angle of the onshore border – a 45% degree angle – or follow the line of latitude from the coast. That would affect how much North Sea can be claimed as "Scottish" (arguing over maritime borders is never simple and has caused wars). However some things are more straightforward than has been suggested, as nearly all the gas fields are clearly and unarguably off the coast of England, not Scotland. I therefore don't believe that the SNP has any chance of negotiating anything near the 90% or even the 80% figure with Westminster for reasons of simple geography.

The claim for 90% is probably an opening bargaining position, and the SNP probably expects to be negotiated down from this figure. Looking at the maps, I think it is more realistic to assume that an independent Scotland would settle for something nearer 50% of North Sea revenues, which of course increases the deficit for an independent Scotland substantially.

I'm very happy to leave the political and economic debates to the politicians and the economists, but it is alarming if their debates are based on assumptions that oil prices and production will remain the same or increase. OGFJ

About the author

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com