Internal controls are critical in oil and gas application systems

Yahya MehdizadehSchlumbergerHouston

Abstract: From seismic analysis to reservoir modeling, geological and geophysical data processing applications are the primary components in determining the value of an asset for oil and gas companies. The extrapolated data feeds the appropriate financial systems to determine revenue and financial position. Therefore, internal controls become a necessity for the application systems that supply the financial data.

As a key element in the new compliance background for public companies in the United States, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) requires expanded responsibility for evaluation of and disclosure about a corporation’s internal controls. Section 404 of the act directs the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to adopt rules requiring annual reports for companies traded on the US stock exchanges to include an assessment of the effectiveness of internal controls and procedures for financial reporting.

Furthermore, 404 goes as far as demanding that the company’s independent auditors attest to and report on the effectiveness of the internal control structure to the board of directors. In addition, section 302 requires management - specifically, the CEO and CFO - to sign off on financial statement fairness and internal control effectiveness.

This act has led to companies investing heavily in becoming SOX compliant using internal resources, external consultants, information systems, and auditing. Initial compliance is only the beginning of the long-term impact of SOX on organizations. It is important that companies ensure that compliance is a means to an end - not an end in itself.

Although the SEC has not yet issued a definition or framework for internal controls, it is expected to closely align with the key internal control concepts of the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). The current COSO chairman states, “. . .that every division in a company needs to have a documented set of internal rules that control how data [are] generated , manipulated, recorded, and reported.” It is important that a baseline is established to measure the continued effectiveness of controls in a dynamic environment.

A data integrity challenge

Seismic data from oilfield assets are interpreted to determine the existence of hydrocarbons in underground formations. Based on the findings, the assets then go through a series of simulations to determine development strategies and to forecast production output. The final result is represented by the amount of oil and can be produced from that asset, measured in barrels per day (bpd).

Corporate management focuses on how many barrels of oil can be produced per dollar spent, while their counterparts on the operations side evaluate what dollar amount can be generated per barrel produced. Therefore, the upstream marketing functions of oil and gas companies play a significant role in the valuation of assets within the financial statements.

Business and petrotechnical applications are key in providing the needed financial data. Their role in extrapolating production and pricing data is critical in forecasting revenues, which have a profound effect on developing an earnings forecast based on future oil and gas production.

Technical, commercial, and compliance requirements need to be satisfied during the various stages of the financial reporting process. As an example, for reserves estimation, geological and geophysical applications are used to assign a value to assets based on the potential oil and gas output from the asset. The financial estimates are then calibrated against other considerations such as commercial risks, cost to produce, corporate objectives, and business drivers. Finally, the numbers are adjusted using industry guidelines and regulations and become an integral part of the assets in corporate balance sheets (see Fig. 1).

Furthermore, because the reserves estimation determines how much oil and gas a company can produce in the future, it impacts the company’s future sales projections. Without adequate controls to ensure the proper recording of such items, the resulting financial data may be unreliable, resulting in damage to management’s credibility with shareholders, regulators, business partners, and the public.

Control systems and the role of IT

Whether through a unified Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system or a collective of best-of-breed operational and financial management software applications, information technology (IT) is the foundation of an effective system of internal controls over financial reporting. Thus, IT professionals are being held accountable for not only ensuring that adequate internal controls are in place, but also for validating the quality and integrity of the information generated.

Although the ultimate responsibility for financial numbers resides with the business managers, their lack of detailed knowledge of these systems makes this a full-time responsibility of the IT staff. Therefore, IT is being tasked with mapping the IT systems that support internal controls and the financial reporting processes to the financial statements.

Unfortunately, ensuring adequate internal controls separately for each business and petrotechnical application is time consuming and costly. It may lead to an inconsistent methodology for controls if no common standard or baseline is followed to implement the controls.

One way to tackle this problem is to step back and look at a bigger picture of how controls can be implemented. Industry analysts such as Gartner and Forrester suggest that a robust control system should consist of five components (see Table 1).

An architecture for compliance

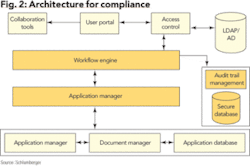

A common workflow engine, applications, and an audit trail manager are integral parts of implementing internal controls for petrotechnical applications. Access to geophysical and geological applications that impact financial numbers should be via a portal where the appropriate rule-based and/or role-based access enforces appropriate access controls.

Role-based access is best validated against a corporate directory containing the job title of every current employee. For example, a reservoir engineer’s access into the portal should only allow him to analyze a specific field from a specific customer to conduct the necessary data modeling. On the other hand, an asset manager logged into the portal should be able to look at the entire oilfield asset to conduct her business activity. Based on the task to be performed and the user role, the right application would be launched.

In this case, the reservoir engineer, based on his role, would have access only to a specific set of applications such as exploration interpreters or prospect viability or simulation modeling tools. On the other hand, the asset manager would not only have access to those tools, but in addition would be able to look at two- and three-dimensional seismic interpretations that would give her a better view of the reservoir.

The workflow process manager ensures that the business process is followed throughout the various stages, interfacing with the application access manager calling the required data from the various databases and feeding it back for data manipulation. This can be demonstrated in production planning process where a number of applications - from production and engineering analysis to data mining to streaming production data - are used to provide remote monitoring and support dynamic production and drilling.

The resulting asset data is then stored in a database that is secured by encrypting the data, key escrow, and data locking. Throughout all transactions, an audit trail is created ensuring traceability of the process for audit or reporting with adequate assurance that the data has not been modified by the time of signoff.

To deploy this framework, the four basic steps to follow are:

• map the various petrotechnical business processes (resulting in a process map similar to Fig. 1, but probably with more detail);

• inventory the applications that are used to support each step of the process;

• select an appropriate workflow engine that works with the existing applications, or can easily be connected to them;

• integrate the petrotechnical processes into the workflow, typing in application calls and log recording features.

While this framework may not be practical to implement for all applications, it should form a baseline for the type of controls that need to be in place to ensure proper compliance. The key to this framework is its focus on process, which helps to implement better controls from a security and auditability standpoint.

Best practices

When it comes to frameworks that help enterprises prioritize their needs for compliance, the COSO enterprise risk management (ERM) framework seems to be one of the better models in existence. The general IT controls section does an excellent job of identifying areas of risk, and in particular, the ones that need remediation to comply with Sarbanes-Oxley.

Because the ERM framework does not provide the specifics of how to implement a compliance system, it is recommended to use control objectives for information and related technology (CobiT), which is an IT process, control framework, and maturity model for auditors, senior business management, and senior IT management.

CobiT focuses on what an enterprise needs to do, along with the IT processes that ensure proper internal controls are in place. According to Gartner [Logan 2004], enterprises that adopt a risk management approach for a control framework will cut the cost of their compliance program by 50 percent during the next five years. Some best practices that can help achieve this are shown in Table 2.

In order for internal controls to work effectively, they have to be planned, implemented, operated, and maintained as a complete system. Furthermore, internal controls must not only be viewed as a technical solution, but also as a core part of organizational culture.

In oil and gas companies, this requires strong commitment from asset managers, operations and production teams, and financial managers. These teams must work together to resolve issues without weakening the controls required for compliance.

Conclusion

There is no such thing as a risk-free environment, and compliance with Sarbanes-Oxley does not create such an environment. In particular, it is generally impossible to detect or prevent intentional financial fraud by properly authorized managers. However, implementing a framework where there is consistency in documented internal controls (with automated workflows, auditability, data security, and integrity checks) can help reduce the risk and create a more efficient working environment.

For upstream oil and gas financial transactions, applications that impact oilfield asset valuation, reserves estimation, and production planning should have internal controls embedded throughout the transactions. Linking the relevant financial reporting risks and the infrastructure that supports the financial controls is a good direction to ensure a proper compliance. OGFJ

References

1. “IT Control Objectives for Sarbanes-Oxley,” Abstract: IT Governance Institute, ISBN 1-893209-67-9

2. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of Treadway Commission (COSO), www.coso.org

3. [Logan 2004] Debra Logan, John Bace, Lane Leskela, “Use a Process Framework for Compliance and Think Long Term.” Gartner report DF-22-3035, May 2004

4. “Visualizing Strategic Business Process Management,” Upstream CIO, February 2005

5. [Nicolett 2004] Mark Nicolett, “IT Security Technologies Can Address Regulatory Compliance.” Gartner report 02252004-04, February 2004

The author

Yahya Mehdizadeh [[email protected]] is director of corporate security strategies for Schlumberger. In this capacity, he is responsible for defining and implementing corporate security governance for Schlumberger’s oil and gas customers. He has held several senior management positions, from leading a start-up business unit focused on delivering smart card-based identity and access management solutions for logical and physical security to building a managed security services offering, to putting together a defense-in-depth strategy for the Athens Olympics, to defining compliance solutions addressing regulatory issues such as SOX and HIPPA. Mehdizadeh holds a masters degree in information systems and management with certifications as a CISSP, CISM, CISA, and GSEC. An active member of the ISSA, ISACA, and a champion at the Houston Technology Center, he regularly collaborates with industry executives and tech start-ups on emerging technology issues and trends.