Embattled Brent

Analyzing threats to the benchmark's viability

Phil Casey,Petroleum Economist, London

Uneasy is the head that wears the crown. This phrase – famously penned by William Shakespeare for the play Henry IV – is surprisingly relevant when discussing today's crude oil markets. The reigning global benchmark is indisputably the North Sea's Brent. Indeed, the US Energy Information Administration estimates that Brent is used to price two-thirds of the world's crude. It successfully displaced West Texas Intermediate (WTI) in March 2013 as the world's most heavily-traded crude grade.

Its grip on the title, however, looks increasingly precarious. Continued North Sea production declines have served as the primary concern and called into question Brent's long-term viability. More recently, outages and disruptions – most critically at the Buzzard field – have led to temporary price spikes and cast doubt on Brent's ability to accurately reflect global crude prices on a day-to-day basis. Consequently, Brent has come under increased scrutiny from traders.

Other potential threats to the benchmark include rising North Sea production costs, an unfavorable tax policy, and growing geopolitical uncertainty from the upcoming referendum on Scottish independence. These criticisms of Brent have led to increased speculation regarding the possible emergence of a rival benchmark, with Urals and Dubai most commonly cited as the leading contenders.

The Paris-based International Energy Agency reported last year that European oil demand was at a 20-year low. Logically, the combination of falling North Sea production and falling European demand should decrease Brent's relevance. Additionally, the widely-held belief that seaborne crudes like Brent are more reflective of global markets than landlocked crudes is highly questionable – pipelines benefit from a flexibility in delivery quantity that is impossible for crude tankers to mimic. This supposed "seaborne advantage" was critical in Brent's overthrow of WTI.

Perhaps most symbolic of all, Shell has announced that the decommissioning of the Brent field – after which the embattled benchmark is named – is well underway. Brent Delta, one of the field's four platforms, reached cessation of production in December 2011. Within the next few years, then, the world's leading oil benchmark will no longer be backed by physical Brent. The price impact of this development will be muted, though. Field production barely exceeded 1,000 b/d in 2013.

When Brent futures were originally introduced in 1988, the contract was based solely on crude from the Brent field, which reached peak production of 400,000 b/d in 1984. Today's contract, as traded on the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), is comprised of a blend of crude grades from four primary North Sea streams – the Brent, Forties, Oseberg, and Ekofisk complexes (BFOE).

The number of North Sea fields underlying the Brent contract, then, has risen from one to a number in the hundreds. Forties stream alone is a blend of crudes from some 70 fields. Platts' inclusion of these additional blends (Forties and Oseberg were added in 2002, Ekofisk in 2007) was meant to counter rapidly falling production at the Brent field. It was only a temporary fix to a more fundamental problem, though.

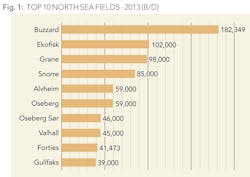

The other flagship fields of the BFOE complex are also in decline. Combined production from Forties, Oseberg, and Ekofisk was only 202,473 b/d in 2013. This was to be expected – those three fields came online in 1975, 1988, and 1971, respectively. The rest of the North Sea is not faring much better. According to this author's analysis, its top 10 fields produced 756,822 b/d in 2013 (See Figure 1). By comparison, the United States alone boasts three shale plays – Eagle Ford, the Bakken, and the Permian Basin – with individual production levels in excess of 1 million b/d.

According to Oil and Gas UK, the country's official trade body, only 15 exploratory wells were spud in the North Sea in 2013. This can be attributed to rising production costs brought about by reservoir depletion. Between 2012 and 2013, extraction costs rose 27% to £17 per barrel. Additionally, the number of fields with production costs above £30 doubled over the same period.

With the UK's unceremonious dumping of its short-lived fracking moratorium in December 2012, these rising North Sea extraction costs may cause some operators to divert their attention to the greener pastures of UK onshore. In July 2013, George Osborne and the UK Treasury announced a proposal to set a 30% tax ceiling for onshore shale gas operations in Great Britain. This tax break is meant to encourage the commercial development of northern England's significant shale gas deposits in the wake of the Bowland Shale Gas Study – a report published by the British Geological Survey which dramatically raised onshore reserve estimates.

New North Sea operations, meanwhile, are strapped with a top tax rate of 62%, with aging fields subject to draconian rates as high as 81%. This tax discrepancy could accelerate the natural migration from the North Sea to new, more exciting plays. If such an exodus does indeed materialize, it will place even further pressure on Brent.

While most criticisms of the Brent benchmark have focused on its ability to stay relevant over the long term, a disturbing trend of production disruptions has begun to threaten its short-term credibility as well. In 2012, a dangerous natural gas leak at Total's Elgin-Franklin field led to the immediate evacuation of 238 platform workers and brought back memories of the 1988 Piper Alpha tragedy. It took nearly a year before Elgin-Franklin came back on-stream.

In Norwegian waters, a compressor breakdown at BP's Ulma platform led to a drop in Ekofisk production last August, while a strike of 700 oil workers shut down the Oseberg and Heidrun fields for several days in 2012. Meanwhile, the North Sea's largest field – Buzzard – has experienced an exceptionally high number of outages over the past several years. An EIA report blamed this on "various technical and operational issues." The field was offline multiple times recently, including for periods in May, June, and August of 2013 and in January of this year. In March, it was announced that Buzzard would be shut down for maintenance for 25 days this summer, beginning in late July. This extended closure is presumably an attempt to address these issues and make the necessary operational repairs.

Disruptions at Buzzard are particularly damaging to Brent's credibility as a benchmark, and not only because of its size. Unlike WTI, which is priced entirely from the NYMEX futures contract, Brent is the result of a complicated pricing cocktail which includes physically-traded oil cargoes (Dated Brent), ICE Brent futures, and a variety of other derivatives.

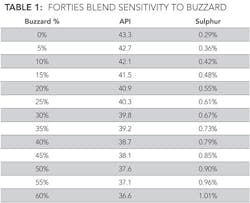

The cheapest of the BFOE blends in the physical (or "spot") market determines the final printed price of Platts' Dated Brent assessment each day. Because the sulfur content of Forties is significantly higher than that of Brent, Oseberg, or Ekofisk, it is the stream that usually sets the Dated Brent price. Consequently, Forties has a disproportionate impact on the Brent benchmark price. Buzzard – which produces a much lower quality crude than most North Sea fields – accounts for over 33% of Forties blend and thus has a significant knock-on effect on Dated Brent prices.

When Buzzard goes offline, Forties prices will jump due to both decreased supply and increased quality. Outages at Buzzard, therefore, have an especially adverse effect on the short-term reliability of the Brent benchmark. The impact of Buzzard crude on the overall quality of the Forties stream can be seen in Table 1.

The ongoing geopolitical saga of Scotland's planned September referendum on independence from the UK is further cause for concern. Preliminary polling suggests a very tight result, and ownership of North Sea mineral rights is a heated subject. Indeed, a popular political slogan used by the Scottish National Party during the 1970s has once more become a rallying cry for Scottish nationalists – "It's Scotland's Oil!"

Whatever the outcome of the referendum, the uncertainty and tension surrounding the vote has left many North Sea operators wary. Though perhaps not severe enough to cause current producers to pull out, the region's increased political volatility may certainly discourage the entry of new participants and require contingency planning by current operators.

Despite the generally pessimistic outlook presented here, there have been some positive developments in recent years that should not be overlooked – most notably in the form of the massive Johan Svredrup discovery along the Norwegian Continental Shelf in 2010/2011. Expected to come on-stream in the fourth quarter of 2019, it has a projected peak production of 500,000 b/d, perhaps the highest output level of any field in North Sea history. Goldman Sachs considers Johan Svredrup to be a low-risk development and estimates a commercial breakeven of $39 per barrel. With gross recoverable reserves estimated between 1.7 and 3.3 billion barrels and a production horizon to 2050, the inclusion of Johan Svredrup crude in the Brent basket would help counteract falling BFOE output and bolster the benchmark's long-term viability.

A discovery such as Johan Svredrup is exceptional, especially in a mature basin like the North Sea. The likelihood of another such find is minimal. Fortunately for the Brent benchmark, then, it is also finding support from a far more mundane source – increased recovery rates from aging fields. Technological breakthroughs and increased commercial incentive from elevated oil prices have extended the lives of many fields.

Apache, a Houston-based independent exploration and production company, is leading the charge in the revitalization of the UK's seemingly-exhausted North Sea assets. At the time of its purchase of the Forties field from BP in 2003, production had fallen to 40,000 b/d and was expected to stop altogether by 2013. Remarkably, through the use of 4D seismic technology and horizontal drilling, Apache has managed to achieve higher production levels at Forties today than at the time of the sale 10 years ago. Other companies have certainly taken note. If replicated on a wide scale, these enhanced recovery methods may prove even more instrumental in salvaging the Brent benchmark than the rogue Johan Svredrup discovery.

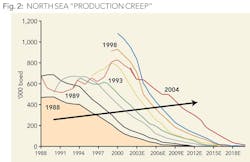

Combined with new discoveries, these enhanced recovery tactics have resulted in a North Sea "production creep." Figure 2 highlights this phenomenon. Essentially, it displays the continued upward revision of production estimates for the North Sea. If history is a good indicator, this figure implies that popular consensus on the North Sea is generally too pessimistic. One can clearly see in the graph, for example, that production estimates for 2012 were much higher in 2004 than they were in 1998.

In conclusion, a number of factors have combined to place unprecedented scrutiny on the Brent benchmark. There can be no doubt that it has entered a period of intense turbulence. Production disruptions, unfavorable tax policies, declines in North Sea output, rising production costs, and a climate of geopolitical uncertainty have caused many to question its short-term stability and long-term viability. Some – including the CEO of the world's largest oil trader, Vitol – have gone so far as to suggest that the Brent basket must be expanded to include crude grades from Algeria, West Africa, and Kazakhstan.

scrutiny from traders.

Among the potential threats

are North Sea production declines,

rising North Sea production

costs, an unfavorable

tax policy, and uncertainty over

the upcoming referendum on

Scottish independence. These

criticisms of Brent have led

to speculation regarding the

possible emergence of a rival benchmark, with

Urals and Dubai most often cited as the leading contenders.”

Despite these threats, certain developments may forestall the need for an immediate overhaul. Coupled with the discovery of the Johan Sverdrup elephant field, continually-elevated oil prices have rendered the employment of EOR tactics at aging North Sea fields commercially viable and thus bolstered the basin's production prospects. The potential for the inclusion of DUC and Troll blends to the Brent basket also reduces immediate pressure on the benchmark.

Upon its discovery, the Brent field was named after the "brent goose" by Shell. Though its current prognosis is not good, it is still premature to declare with certainty that Brent's goose is cooked.

About the author

Phil Casey graduated Magna Cum Laude from HEC Paris with a Master of Science in Energy & Finance. He completed undergraduate studies at Georgetown University with a double-major in Finance and International Business. He has previously interned at Merrill Lynch in Washington, DC and in the M&A team at Santander Global Banking & Markets in Paris. He is a member of the Society of Petroleum Engineers.