Trade secret protections

Energy companies may need to re-evaluate their protocols.

Brian Cathey, Pierce & O'Neill LLP, Houston

On September 1, Texas became the 48th state to adopt a form of the Uniform Trade Secrets Act. The UTSA was drafted in an effort to provide improved and uniform trade secret protection throughout the 50 states.

While some jurisdictions have already applied their version of the UTSA to the oil and gas industry, the sheer magnitude of the Texas oil and gas industry means that Texas's adoption of the UTSA could have a significant impact on trade secret protections for the oil and gas industry beyond Texas. As a result, companies in the oil and gas industry should take this occasion to identify information that is protectable as a trade secret under the UTSA, and re-evaluate their protocols for protecting that information, regardless of whether they operate in Texas.

Nature and scope of trade secret protection

A trade secret arises as a matter of law. Broadly speaking, a trade secret is any information which confers an advantage over one's competitors because it is not generally known or readily ascertainable by proper means. When a party acquires a trade secret by improper means, it commits an act of misappropriation, which entitles the owner of the trade secret to sue for damages and/or for an injunction preventing the disclosure or use of the trade secret. Improper means of acquiring a trade secret include theft, bribery, misrepresentation, breach of a duty to maintain secrecy, and espionage.

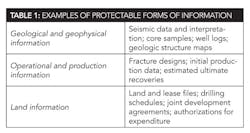

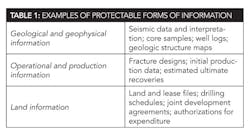

Virtually every company in the oil and gas industry has trade secrets, and these trade secrets are often some of a company's most valuable assets. Under the UTSA's broad definition, a broad spectrum of information may be protected as a trade secret. To be protected as a trade secret, information only need (i) have actual or potential independent economic value, (ii) not be generally known or readily ascertainable by proper means, and (iii) be the subject of reasonable efforts to maintain secrecy. Table 1 provides a few examples of the multitude of geological and geophysical, operational and production, and land information that may qualify for trade secret protection.

Under common law, some courts required information to be in "continuous use" in the operation of a business to obtain trade secret protection. Thus, information that had not yet been put to use and information that had value from a negative viewpoint––for example, information proving that a certain approach would not work––were potentially not protected. Both types of information are arguably encompassed by the UTSA's definition, however. Thus, things like geological and geophysical information that would show that a prospect does not exist may qualify for trade secret protection under the UTSA.

Protocols for protecting trade secrets

Companies must take precautions to safeguard any information they intend to be treated as a trade secret. A trade secret, after all, requires a substantial element of secrecy. Protocols for maintaining information's confidentiality are, therefore, an essential element in establishing and maintaining trade secret protection. Potential protocols companies in the oil and gas industry may employ to maintain confidentiality include:

- Conducting confidentiality training at hiring;

- Enacting a confidentiality policy that is acknowledged by employees at the time of hire;

- Limiting access to confidential information to those with a "need to know";

- Conducting exit interviews to advise employees about their duty to keep information confidential; and

- Executing confidentiality and non-disclosure agreements, particularly with outsiders.

Issues confronting the industry

While the UTSA had enhanced the uniformity of trade secret protections for companies in the oil and gas industry, the UTSA is not a panacea. A number of trade secret issues continue to confront companies in the industry. One issue involves the voluntary disclosure of information by companies to outsiders, typically as an inducement to a proposed oil and gas transaction. While companies frequently use confidentiality and non-disclosure agreements in these situations, many forms are currently in use. The provisions in these forms need to be carefully reviewed and modified for the particular transaction contemplated.

One area that is commonly overlooked when using form confidentiality and non-disclosure agreements is the definition or description of the area to which the agreement applies. Difficulty arises when a court is asked to enforce such an agreement, particularly under the statute of frauds. The statute of frauds provides that a contract subject to it must furnish the definition or description of the area to which it applies with reasonable certainty. When a description fails to meet this standard, the agreement may be unenforceable, and the disclosing party may not be able to enforce it by specific enforcement or recover damages for its breach.

Because of the transitory nature of employment relationships in the oil and gas industry, trade secret issues also frequently arise in connection with former employees who move to a competitor. Under the UTSA, an employer is generally only liable for misappropriation when it knows or has reason to know that a trade secret was acquired by improper means, rather than accident or mistake.

Thus, if an employee obtains a new job and misappropriates a former employer's trade secrets, the new employer will generally not be liable for misappropriation of trade secrets, absent actual or constructive knowledge by the employer that the information was obtained by improper means. Because of this, the burden may rest on an employer to notify a former employee's new employer of actual or threatened misappropriation in order to trigger the new employer's liability.

Since employers are not necessarily liable for misappropriation by new employees, it is imperative that employers take steps to protect trade secrets when their employees depart. As indicated above, protocols for protecting trade secrets in this circumstance may include a company confidentiality policy that is acknowledged by the employee at the time of hire, as well as exit interviews to advise employees about their duty to keep information confidential. With regard to key employees, a non-competition agreement may also be used.

While the UTSA has enhanced the uniformity of trade secret protections among the 50 states, state laws regarding the enforceability of non-competition agreements still vary widely. The Texas Business & Commerce Code, for example, defines a number of specific requirements for an enforceable non-competition agreement that is entered into or performed in Texas. As a result, oil and gas companies operating in multiple states should determine whether the non-competition agreements they use are enforceable in the states where the employees perform their duties, in addition to the state where the agreement is executed.

In some circumstances, the UTSA may permit an employer to obtain an injunction against a former employee who joins a competitor or starts a competing business, even before any trade secret has actually been used. Under the UTSA, a court may enjoin or prevent "actual or threatened" misappropriation. Based on the UTSA's "threatened" language, a court may permit an injunction when a former employee's disclosure of a trade secret is imminent. However, courts are generally reluctant to enjoin such threats of misappropriation.

Another trade secret issue confronting the oil and gas industry involves the submission of information to governmental agencies, principally in connection with state hydraulic fracturing disclosure requirements. Since the commercialization of hydraulic fracturing more than 60 years ago, companies in the oil and gas industry have invested millions of dollars in researching and developing hydraulic fracturing to stimulate production. Evidence suggests that a substantial number of chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing fluid may qualify for trade secret protection. A 2012 analysis, for example, found that companies claimed trade secret protection for 29% of the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing fluid in Texas.

Recently, perceived environmental and health concerns have prompted some oil and gas producing states to adopt mandatory disclosure requirements for hydraulic fracturing chemicals and chemical concentrations. In order to protect the substantial investment oil and gas companies have made in hydraulic fracturing, most states carve out some protections from disclosure for trade secrets. Texas, for example, provides that a company may withhold from disclosure information for which it claims trade secret protection, but provides affected property owners and their neighbors may challenge that claim.

Interestingly, Texas's mandatory disclosure regulations have not been amended to adopt the UTSA's trade secret definition. Instead, Texas's regulations continue to analyze trade secret claims for chemicals and chemical concentrations under the previous six-factor test for a trade secret.

Because the UTSA was enacted to enhance the uniformity and certainty of trade secret protections, the six-factor test in the Texas regulations was conceivably superseded by the adoption of UTSA. However, until the regulations are amended, the issue of what chemicals and chemical concentrations qualify for trade secret protection will remain.

Remedies and judicial protections offered by the UTSA

Because misappropriation cases often involve substantial attorneys' fees, as well risk further disclosing the very secrets sought to be protected, some companies have elected not to pursue otherwise meritorious misappropriation claims. The UTSA attempts to address both of these issues.

First, under the UTSA, a prevailing party may be entitled to recover its attorneys' fees under certain circumstances. At common law, there was typically no basis for an award of attorneys' fees for misappropriation of trade secrets, absent some other related cause of action providing for the award of such fees. Second, the UTSA requires courts to preserve the secrecy of an alleged trade secret during litigation.

Under the form adopted by Texas, there is "a presumption in favor of granting protective orders to preserve the secrecy of trade secrets." In the protective order, the court is authorized to, among other things, include "provisions limiting access to confidential information to only the attorneys and their experts" and order parties not to disclose alleged trade secrets.

Conclusion

Because the UTSA was drafted in an effort to provide improved and uniform trade secret protection throughout the 50 states, Texas's adoption of a form of the UTSA should have a significant impact on trade secret protections in the oil and gas industry beyond Texas.

Under the UTSA, a wide range of information compiled by companies in the oil and gas industry may qualify for trade secret protection, so long as adequate secrecy is maintained. The UTSA does not, however, resolve all trade secret issues, and companies within the industry should be vigilant in recognizing these issues.

About the author

Brian Cathey is an attorney at Pierce & O'Neill, LLP in Houston, where his practice focuses on complex civil litigation. He routinely advises major and independent oil companies in oil and gas, land, and commercial cases. Cathey earned his BBA from Texas A&M University in 2007 and his JD from the University of Michigan Law School in 2010.