Reserve based finance

A tale of two markets - Part 3

Jason Fox

Bracewell & Giuliani

London

Dewey Gonsoulin

Bracewell & Giuliani

Houston

Kevin Price

Société Générale

London

This is the third part of a four part article examining the evolution, practices and future of the reserve based finance markets in the US and internationally. January's Part 1 examined facility structures and sources of debt for the upstream sector in the international market. In February's Part 2, the authors examined the structures and sources of debt for the sector in the North American market, amortization and reserve tails, reserve analysis and bankable reserves, as well as the Banking Case and assumption determination. In this, Part 3, the authors examine debt sizing and cover ratios, loan facility covenant packages and hedging.

Debt sizing and cover ratios

The US RBL approach to determining the Borrowing Base Amount is very 'black box'. The Borrowing Base Amount is determined by a process whereby the lender serving as the administrative agent recommends to the syndicate lenders its own suggested Borrowing Base Amount based on (a) the reserve reports (b) other field data provided by the borrower and (c) other relevant variables, including the presence or absence of hedging. The recommended amount is then subject to lender approval. In the case of a typical US senior bank borrowing base revolving line of credit, the loan documentation sets out no methodology for the calculation (in some mezzanine loans, however, rigid formulas may be used to determine loan amounts). The lenders have absolute discretion over how they calculate the Borrowing Base Amount, although to give the borrower some protection there is usually some wording that each lender will determine the Borrowing Base Amount in a manner consistent with its "customary oil and gas lending criteria". The borrower, however, is also protected from the arbitrary nature of the process by the fact that competitive pressures will often force lenders to be reasonable (and in some instances, to stretch to arrive at the desired borrowing base amount). As noted in Part 2 of this Article, the Borrowing Base Amount is primarily sized by "risk weighting" the reserves and the approach is relatively common across banks. In addition, as noted above, other factors may affect the Borrowing Base Amount. Some of these factors include (but are not limited to) the existence of other debt (e.g. second lien obligations, high yield bonds, etc.), the existence or absence of hedging, the existence of title defects or potential material environmental liabilities and operational issues.

An example of how this approach is taken is shown on the next Table which is a theoretical extract from a borrowing base model. In the "RISKED" section of the table the percentages indicate the risking or adjustment factor applied to the various sub categories of Proved Reserves. In this example 100% of the value of the PDP (Proved Developed Producing) Reserves are included in the NPV analysis, but only 70% of the PDNP (Proved Developed Non-Producing) reserves are taken into account and finally only 40% of the PUD (Proved Undeveloped Reserves) are taken into account. In all cases not only are the reserves are adjusted by the relevant factor, but also the associated costs. So only 40% of the PUD capex will be included in the model run in this case.

The bottom line of this block of the table shows how these reserve categories, having been risk-adjusted, then contribute to the makeup of the aggregate NPV value – in this example 67% of the Borrowing Base NPV value is coming from PDP, 5% from PDNP and 23% from PUD (with the remaining 5.7% coming from the incremental value of hedges above the bank price deck). In cases where the PUD contribution to the NPV was considered excessive, perhaps above 30% or so, then an iteration to the PUD "risk factor" (which in this case is 40%) might be made adjusting it (taking less PUD's, so maybe reducing it to 35%) until the contribution to the NPV of the borrowing base was reduced to a level deemed acceptable. The amount of PUD's included will vary depending, amongst other things, on the cover ratio of the amount of debt available to the NPV. If the cover ratio is high then more PUDs may be acceptable, but if the cover ratio is low (say 1.5 or less) then a borrowing base made up more of more PDP might be desirable. The whole process is somewhat iterative and subject to banks' internal guidelines. However the pressures of the market mean that there tends to be a trend to a "market" norm. In the below example the cover ratio is 1.78 meaning that the $1 billion dollar borrowing base is underpinned by an estimated NPV for collateral valuation purposes of $1.781 Billion. The table also shows the contribution to NPV made by different commodities – (oil, gas and NGLs).

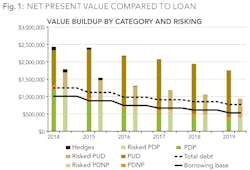

Figure 1 shows the result of the Borrowing Base analysis exercise in comparing the forecasted reserves and production from the company's most recent reserve report to the amount of reserves and production included in the banking case expressed as NPV value at a given price assumption. It can be seen that the amount of PUD reserves (the red solid bar) included in the bank calculation are significantly reduced from the reserve report whereas full value is given to the PDP (green bars). In this example the Borrowing Base available is shown in a solid black line (reducing over time with reserves unless they are replaced or increased). The company in question also has some subordinated debt (shown in dashed line).

International RBLs provide for a much more transparent and formulaic approach to the calculation of the Borrowing Base Amount. The Borrowing Base Amount will be determined by the Banking Case. It is driven by the assumptions plugged into the model (which are determined following an iterative process between the borrower and the Technical Bank) and applying cover ratios (which are set out on the facility agreement) to the discounted future net cash flows from the borrowing base assets. The Borrowing Base Amount for a given period will be the lower of an amount which provides for an agreed Project Life Cover Ratio (typically 1.5:1) and an agreed Loan Life Cover ratio (typically 1.3:1). Sometimes there is also a Debt Service Cover Ratio, although this tends more to be more a way of monitoring that future net cash in each semi-annual period will be adequate than a driver of debt capacity. As an undiscounted number the Debt Service Cover Ratio is essentially a liquidity test rather than a value test.

If at inception the borrowing base portfolio is predominantly based on OECD assets then sometimes there are limits on the portion of the NPV of cash flows which can be derived from assets in non-OECD countries. Obviously for facilities where, at inception, the assets are exclusively or predominantly in non-OECD countries the loans will be priced to reflect that and to attract banks active in (and with country limits for) the relevant region or country.

Similarly, if a facility benefits from a low margin because there is a high proportion of producing fields (as opposed to development assets) there may be a limit on the portion of the NPV of cash flows that may come from assets under development.

The covenant package

It is fair to say that there are more similarities than differences in the typical covenant packages seen in US and International RBLs, but there are some differences worth noting. In general the differences can largely be attributed to the fact that US RBLs are heavily sized against proved developed producing reservoirs and not development projects. So the loan covenants in US senior bank borrowing base facilities tend to be somewhat lighter on a comparative basis. Mezzanine facilities may have much tighter restrictions because of the higher development risk and fewer producing assets that are typically associated with such transactions. As noted in Part 1 of this article, because the International RBL market developed out of project finance, the covenant package in International RBLs has more of the features you would see in a project financing (although the degree of control lenders apply does vary considerably depending on the number of fields in the borrowing base and the proportion which are not yet producing). A few particular points are worth noting:

- there is typically more focus in International RBLs on the field related documentation to which the asset owning group members are party ( licenses, joint operating agreements, offtake agreements etc.) and controls / triggers linked to these

- in International RBLs there will usually be a suite of project accounts, a requirement that revenues pass through these accounts and some sort of cash flow waterfall, although there is a huge variation in the degree of control depending on number and nature of the fields in the borrowing base. It is unusual to see a project account regime in US RBLs (although the pledging of bank accounts as collateral is fairly common as part of a US RBL collateral package)

- as noted above, the Banking Case is a central feature of International RBLs and is a prominent feature in International RBL documentation (whereas it does not feature at all in US RBL documentation). In International RBLs, the Banking Case is not only used to drive the calculation of the Borrowing Base Amount and the testing of cover ratios but, in development financings, it is also typically used in connection with the monitoring and control of expenditures by the borrower

- following the failure of a prominent North Sea exploration and production company in 2008 (Oilexco North Sea Limited) due to a variety of factors but, in particular, huge cash leakages on commitments on non-borrowing base assets, it is now standard for International RBLs to include a forward looking group liquidity test to give lenders visibility on the future consolidated liquidity position of the borrower and its affiliates

- because independents in the US typically raise funds through a range of debt products and in, particular, raise significant debt through the bond markets, US RBLs tend to be less restrictive on third party debt (except in instances involving early stage companies with fewer producing assets). This feature looks set to change as the high yield market outside North America develops and an increasing number of non-North American independents look to the bond markets to diversify their funding sources.

Hedging

Commodity price volatility has always been with us and is the single biggest variable in forecasting EBIT for non-integrated exploration and production companies. Nowhere has this volatility been more pronounced than in the context of the recent collapse in US gas prices. Commodity hedging often has a role in reserve based lending both in the US and elsewhere. Many of the features of how hedging is handled where a company has an RBL facility are common to both the US and international markets, but there are some differences. Perhaps the biggest difference is the geological background. Often the fields that serve as the collateral basis for RBLs in the US are now "resource plays". These plays are unusual in that while the initial decline rates can be rapid and type curves take some time to establish on newer plays, the risk of a proved undeveloped drilling location being "dry" is far lower than in conventional reservoirs. Also, these resources are based onshore with the companies developing them often having constant drilling programmes converting PUDs to PDP.

That means that for companies that have active drilling campaigns and rig resources more aggressive hedging that takes account of this rapid conversion of very low risk PUD to PDP as a result of near constant drilling can be undertaken and this is a general trend in the US market. Further analysis of the credit risk issues regarding hedging and production predictability in both the US and the international markets can be found in Kevin Price's article "Hedging is an effective risk management tool for upstream companies" in the November 2012 edition of OGFJ. The following paragraphs examine how RBL facility documentation typically addresses hedging.

Enhancement of the Borrowing Base

The Borrowing Base Amount in an RBL facility will be determined by the lenders based on a wide variety of factors but at, its core, is the assessment of the projected cash flows associated with the volumes of hydrocarbons forecast to be produced from the borrowing base fields. Extensive technical analysis is performed by the Technical Bank (in International RBLs) or Administrative Agent (in US RBLs) to determine the quantity of reserves expected to be produced in a given period as well as the cost to produce such reserves. The commodity price utilized for the purposes of the borrowing base calculation (the "price deck") will be a conservative one, determined by the lenders, and will be materially lower than the prevailing market spot price. If, however, the producer has locked in a fixed price for its production through a hedge or swap, then the lenders will generally be amenable to giving the borrower credit for the cash flows associated with the hedge (rather than what the price deck would yield). These enhanced cash flows will result in an increase to the Borrowing Base Amount (compared to what it would have been without hedging). Because borrowers typically want as high a Borrowing Base Amount as is possible, most lenders will then quote them the higher number but also require the minimum hedging needed to achieve that number. These hedges must be maintained and if they are unwound or restructured, resulting in a material decrease in pricing support, the lenders may require a redetermination of the Borrowing Base Amount.

Limitations on Hedging Activities

Mandatory hedging is rare in International RBLs and unusual in US RBLs unless (a) it is done in the context of protecting against downside where the borrower has high leverage (such as post an acquisition or with second lien debt in the capital structure) or (b) it is required to achieve the required Borrowing Base Amount as noted above.

The bigger issue for lenders is making sure that there are protections in place to avoid the producer overhedging. Both US RBL and International RBL facilities will usually restrict the volumes that a producer may hedge over a given period of time. Lenders are concerned if a borrower enters into swap contracts covering notional volumes that are at or near the borrower's expected production levels because, if production declines, the company may become "overhedged." In a typical swap the producer pays the variable price for its production to the swap counterparty in exchange for a fixed price. As the company sells its production in the market, it receives the variable market price for such production and (notionally) pays this to the swap counterparty in exchange for the fixed price. In practice the two parties net the payments and the party that is "out of the money" pays the net amount to the party that is "in the money." If, however, there is no production to sell and hence no revenues to net against, the company will be forced to pay such swap obligations out of its own cash reserves. To mitigate this risk lenders invariably impose limitations on the notional volumes that may be hedged.

In the US limits historically have ranged from 80% to 90% of anticipated production from existing PDP reserves. Some lenders have, however, allowed producers to sometimes (and this is increasingly the trend in the case of non-conventional reserves) hedge a percentage of all proved reserves anticipated to be converted to PDP reserves during the life of the hedge. In International RBL the limits on hedging are usually much stricter than in the US. This difference is for a number of reasons. Firstly this reflects the usually greater uncertainty of PUD reserves on conventional reservoirs and so the associated risk of reservoir performance. Secondly it reflects the fact that lenders are dealing with predominantly offshore fields with less well count and much more time and cost taken in remedial drilling and well intervention. Finally another important factor is the fiscal regime. In many places in the world the hydrocarbons recovered are taxed at well-head prices so hedge losses and gains are not offset at the corporate tax level and hedging too much on such fields can lead to a situation where a company has to pay tax on wellhead prices and cannot offset hedge losses against those tax liabilities. Typically International RBLs limit hedging to something in the range of 50- 75% of Banking Case projected production. A few other standard limitations (common to both US and International RBLs) include: (i) strength of counterparty (usually tied to a minimum long-term unsecured debt rating) (ii) tenor (usually not more than three to five years) and (iii) types of collateral or credit support. Finally, there is always a general prohibition on speculative hedging.

Collateral and Ranking

Most independent exploration and production companies will have to offer security to obtain competitive pricing when entering into a derivative instrument involving a contingent liability for it (e.g. a swap). In other arenas, security for hedging often takes the form of cash margin or letters of credit. In the upstream finance markets, however, this is not normally the case for two reasons. First the "negative pledge" covenant in the Facility Agreement will usually prohibit the giving of such security, secondly, an independent exploration and production company would typically not want to tie up its cash or letter of credit capacity. So the more usual route is to use the company's own oil and gas reserves to serve as collateral for the hedges. If the swap counterparty is a lender or an affiliate of a lender, the facility documentation will generally provide that those hedges are secured with the loans on a pari passu basis. There can be issues, however, if a lender enters into a hedge and then subsequently leaves the bank group. In those circumstances the normal position under US RBLs is for then existing hedges to remain secured but no new hedges by that lender (or its affiliates) will be secured.

In International RBLs a variety of different approaches are seen to address this issue but there seems to be a developing trend towards the US position. In the US market in recent years it has become more common to allow third party hedge providers (i.e. counterparties that are not part of the borrower's senior bank group) to share in the collateral. In such instances there will be an intercreditor agreement which governs certain aspects of the collateral sharing arrangement. In International RBLs sharing of collateral with non-lenders/non-lender affiliates does not occur. Indeed it is not uncommon for facilities to entirely prohibit hedging with non-lenders (even for products like "puts" which involve no contingent liability on the borrower).

Voting Rights

Both in US and International RBLs, lenders do not get voting rights for hedging exposure (voting typically being done only by reference to Commitments under the loan facility) though occasionally in International RBLs one sees voting rights for lenders (in their capacity as hedging counterparties) where a hedge has been closed out and the hedging termination payment has not been paid. Lender affiliates providing hedges do not typically need or require any such voting rights because such affiliates can be protected by the voting rights afforded to the lenders themselves. Facility agreements do, however, often contain limitations on amending certain provisions without the consent of the lender affiliates undertaking hedging (e.g. no amendment to the guarantee/security package in a way that would be prejudicial to the hedge counterparties). As noted above, in the past decade or so in the US market there has been an increased willingness by senior lenders to allow third party (non-lender) hedge counterparties to share in the senior lender collateral package so long as a detailed intercreditor agreement is in place to manage the arrangement. Third party hedge providers obviously don't have voting rights under the facility agreement and will therefore insist upon having voting rights granted to them in the intercreditor agreement. The voting usually involves a majority or supermajority percentage of the combined loan and hedge mark to market exposure.