Shareholder Activism

Activist successes will likely spawn more challenges to management

James Constas, EnerCom Inc., Denver

For many oil and gas companies, 2013 was the Year of The Activist. The petroleum industry, especially the upstream segment, has provided fertile ground for activist investors for decades. Last year, multiple forces combined to create a new surge in shareholder activism.

In the 1980s, activists like T. Boone Pickens found E&P companies attractive targets, anticipating that they could buy oil in the ground in the form of proved reserves cheaper than actually drilling for it. Additionally, oil and gas companies made easy targets of themselves with ill-conceived diversification into alternative energy, real estate, and technology.

You may recall that Mobil owned Montgomery Ward. It did not help matters that oil companies had a penchant for hoarding cash. In this first wave of activism, so-called "corporate raiders" sought to oust management teams to clear the way for breaking up companies or forcing management to buy back their shares at a profit.

Fast forward to 2013 and, unlike in the past, efforts in this second wave of activism were more likely to gain approval from large institutional shareholders. As the result of several contributing factors, the fingerprints of activists on the oil and gas industry over the past 12 to 18 months are numerous.

The first, and maybe most visible, activist casualty in 2013 was former chairman and CEO of Chesapeake Energy, Aubrey McClendon. Long-time investor activist Carl Icahn was instrumental in pressuring the Chesapeake board for a change in leadership and stronger board oversight. Icahn's efforts eventually culminated in McClendon's resignation in April 2013 and installation of an almost completely new board. Since then, activists have swarmed into the oil and gas sector.

Also in 2013, Elliott Management Corp. was successful in forcing John Hess, then chairman and CEO of Hess Corp., to relinquish his chairman position to an outsider in May of that year. Hess remains CEO, and despite the changes at the top, Elliott indicated they were not done pushing for change. Hess and Elliott reached an agreement to add five new board members. The company then began to shed non-core assets and initiated a stock buyback program, putting more cash into shareholder hands.

At March 31, 2014 had purchased a cumulative 31.9 million shares of common stock at a total cost of approximately $2.54 billion for an average cost of $79.53 per share. The total shares purchased through the first quarter of 2014 represent about 9% of fully diluted shares when the repurchase program began.

Hess more recently announced on May 22, 2014 that it had agreed to sell its retail business to Marathon Petroleum Corporation for $2.6 billion in cash. The company earmarked proceeds from the sale for additional share repurchases, and that it had increased its share repurchase authorization to $6.5 billion from the original $4.0 billion. The sale of the retail business culminates a string of asset sales, making Hess a pure-play E&P company. Since March 2013 when the company announced it was divesting assets to become a US pure play E&P company, Hess reported asset sales of more than $12.0 billion.

Icahn later targeted deepwater driller Transocean and rallied enough proxy votes to change leadership of that company. In November 2013, the company announced it had come to an agreement with Icahn, then its third-largest shareholder, to pay a $1.1 billion cash dividend and institute an $800 million cost-cutting program.

First Pacific Advisors LLC (FPA) led the effort to force Occidental Petroleum Corp.'s CEO Ray Irani into retirement in May 2013.

Activists forced Murphy Oil Corp. to spin-off its retail gasoline business in August 2013 and pay a special dividend.

Seven years after Tom Ward paid $500 million to buy Riata Energy, which eventually became SandRidge Energy, activists asked him to leave in June 2013. Don't cry for Ward, since the SandRidge termination was without cause, Ward was eligible to receive a $53.3 million lump-sum separation payment, vesting of 6.3 million shares of previously issued restricted stock, and his base salary for the next 36 months. He started a new company in October, 2013, called Tapstone Energy.

JANA Partners LLC disclosed a 15.5% stake in QEP Resources Inc. in October 2013. In its public letter to the QEP board of directors, JANA identified the value of the company's midstream assets as not being realized and that management "spurned our numerous attempts to help them do so." On Dec. 2, 2013, QEP announced it was pursuing a divestiture of its midstream business.

In January, QEP implemented a $500 million share repurchase program, named two new board members, and announced the retirement of long-term QEP board member Keith Rattie (former chairman and CEO of Questar, the company from which QEP spun-out in 2010). The changes kept coming with the February announcement that William Thacker, a JANA-approved appointee, had been added to the QEP board, ostensibly to assist with the midstream business spin-out.

We doubt this string of activism is over, and stories of past activist successes are likely to encourage more challenges to management. One thing we are confident about is that whether management teams like it or not, activists are currently scouring filings, investor presentations, websites, and analyst reports in the search to uncover their next target of opportunity.

What activists want

Rarely do activists want corporate control, seeking to replace the executive in the corner office for its own sake; rather they are seeking to effect change that in their view will increase the value of their holdings. What activists want is simple, and it is the same thing that savvy management wants – to make money.

How activists go about turning a profit from their involvement differs and depends on a company's specific circumstances. Increasing corporate control with more board seats is a way to push for strategic change, such as the divestment of assets. Some corporate raiders may indeed be interested in acquiring a company in a hostile takeover, ostensibly to break it up and sell off the parts at an aggregate price higher than the value inside of the existing corporate structure. Pushing for a share buyback program or special dividend is one way to extract value from a balance sheet flush with cash.

Returning cash to shareholders is not necessarily a bad thing. When a company's business model is scalable, repeatable, and profitable, investors are willing to bid up the share price. The ability to use the least amount of cash to grow production or cash flow is good economics.

Core Lab's annual capital program approximates the company's annual depreciation expense. The company spends about 10 cents to generate $1 of cash flow. On May 16, 2014, CLB shares traded at 23.5 times forward estimated cash flow and had a 1.3% dividend yield. The company's "shareholder capital return program" has returned more than $1.66 billion to its shareholders via diluted share count reductions, and special and quarterly dividends over the past 11 years. For lack of a better term, Core Lab's management team is behaving like internal activists by making good capital allocation decisions, avoiding inadvisable diversification moves, and returning excess cash to shareholders.

Not every management team is so shareholder-friendly. When management is perceived as obstructionist, increasing corporate control with more board seats is a way for the investor to push for strategic change, such as the divestment of assets. Some corporate raiders may indeed be interested in acquiring a company in a hostile takeover, ostensibly to break it up and sell off the parts at an aggregate price higher than the value inside of the existing corporate structure.

T. Boone Pickens made a business model out of pressing his agenda to close value disconnects with the practice of taking a position in a public company and then threatening a hostile takeover. To make Pickens go away and end the threat, the target company would repurchase his shares at a profit. Nearly all of Pickens' threatened buyouts were never completed. During the 1980s, his attempts to takeover Cities Services, Gulf Oil, Phillips Petroleum, and Unocal did not succeed. However, Pickens did pick-up other assets in the process. We're not suggesting that Pickens was against the business. He is a capitalist, he was rational, and knows that it is about shareholder returns.

Growing support for activism

Today's investor activists rarely threaten a hostile takeover outright, and they almost always, for lack of a better term, "win," because they tend to be rational. What management often mistakes as a battle for their jobs is usually a well-thought-out plan to turn a profit, which appeals to shareholders, especially money managers seeking above-market returns to meet the high expectations they created in the minds of clients.

The proxy-advisory firm Institutional Shareholder Services Inc. reported that activists won 70% of all proxy contests in the first half of 2013, up from 43% in the prior year. The success rate at small companies (market capitalization of less than $100 million) was 64%, and better for larger companies at 75%. That improvement suggests that institutional shareholders increasingly view activists as acting in their interests. Whether that is due to activists choosing better targets or the targeted companies having greater institutional ownership sympathetic to activist concerns is unclear.

In 2013, Icahn Enterprises LP had successfully negotiated board seats with seven companies, avoiding a shareholder vote each time, as well as avoiding an embarrassing public war of words and accusations. Avoiding unwanted publicity that negatively impacts a brand and the very real costs of money and management distraction associated with fighting activists may help explain why chairmen are opening the doors to the boardroom more readily.

Activism, it seems, has become something of its own asset class. On the Icahn Enterprises website, the firm boasts in an archived presentation dated Nov. 26, 2013 that "a person that invested in each company on the date that the Icahn designee joined the Board, and that sold on the date the Icahn designee left the board (or continued to hold until Nov. 15, 2013 if the designee did not leave the board) would have obtained an annualized return of 28%." Clearly, activism can be a profitable investment strategy.

And, at age 78, Icahn is not slowing down. Based on the company's May 2014 roadshow presentation, Icahn Enterprises reported it had $5.9 billion invested in energy holdings as of March 31, 2014, its second-largest sector holding behind automotive. Impressively, Icahn Capital advertised a 31% gross return for 2013.

On Wall Street, market-beating returns for investors are like honey for hungry bees. The thirst for profits has helped activist funds maintain a steady stream of capital inflows while many hedge funds have seen investors pulling their capital out. We note that the holdings of noted activist JANA Partners LLC had a market value of $5.7 billion on Dec. 31, 2013, up from $3.4 billion from the previous year. As activist funds grow assets under management, there becomes greater pressure on them to find new targets.

Avoid activists by thinking like one

Given that the vast majority of activists do not take control of the companies they pursue, it would appear that those companies that proactively shed non-core assets, provide transparency about growth plans, exhibit good corporate governance and employ management teams who are not entrenched but instead recognize that they are running a public company, should be seen as good long-term investment opportunities. Here are some suggestions for creating long-term value and avoiding a visit by an activist shareholder.

Define your brand, and stick to it

Proactively manage the five elements of your brand: Brand Promise, Brand Position, Brand Story, Brand Associations and Brand Personality. At its highest level of execution, a brand is the aggregation of everything your company does to build value. Managing the five brand elements proactively improves the effectiveness of communication and even potentially your fundamental performance. Once you have defined your company's Brand Promise and the core competencies needed to deliver it, never stray from it and execute it with enthusiasm. Ill-conceived diversification plans, acquisitions and a risky capital structure can lead to confusion in the market and complicate the valuation process (most likely leading to a case of undervaluation, which tends to attract activists).

Never forget that oil and gas is a cyclical business

In the shale era, it is easy to forget that energy remains a cyclical business. Demand for energy in general, and oil and natural gas in particular, is derived from a variety of factors with the most important being the global economy (at least for crude oil). Investors haven't forgotten this, and neither should management teams. Spoiler alert: Commodity prices are subject to change at any moment and without warning.

Bomb-proof your balance sheet

Keeping all of the above in mind, financial flexibility (i.e., high liquidity and low debt) is not something one values until it is needed. The problem is that we never know when that time will come, so it makes sense to keep the balance sheet free from excessive leverage.

We counsel management teams to look at financial risk not only from the banker's viewpoint, but also from the seat of the equity holder. For example, commercial lenders and bondholders look at debt from the perspectives of collateral risk, based on collateral or proved reserves, the ability for the outstanding debt to be repaid (usually measured by the ratio of debt-to-EBITDA) and the ability to service the interest. That is all well and good for bankers, but activists have a different view of leverage.

As equity investors, activists consider debt a reduction in intrinsic value, or net asset value. The most readily available fundamental bases for measuring intrinsic value in the oil and gas industry are proved reserves and flowing production volumes. These measures of asset volume provide the basis for calculating valuation metrics like dollars per barrel of oil equivalent of proved reserves or dollars per flowing barrel per day, with "dollars" in both cases being measured as Enterprise Value (EV). Since EV includes the combined value of equity, debt and cash, it is a good measure for comparing the fair market value of companies having different capital structures.

To a stockholder, a balance sheet strained by a heavy debt load necessarily impacts residual equity value, because they are at the bottom of the food chain. In a liquidation scenario, shareholders only get paid once all the lenders have been repaid, in many cases leaving little or nothing for equity holders. When financial risk, and debt, gets too high in the eyes of equity investors, they start to get nervous because the abstraction of the liquidation pecking order becomes more real. To maintain some semblance of fair market value using EV-based valuation measures for intrinsic value, equity multiples necessarily have to fall as debt increases.

If true, then we have to ask how much is too much debt? Our research suggests that when debt exceeds approximately 45% of market capitalization, we find less variability in equity multiples, marking the point at which financial risk is perceived to materially impact equity value. We do not suggest that a company with leverage above the 45% mark isn't capable of generating returns for its investors, as company catalysts like a new discovery can renew the market's interest in a name in hopes of seeing an uptick in net asset value. See Fig 1. A catalyst, in fact, could be the accelerator to reducing the debt-to-market cap ratio.

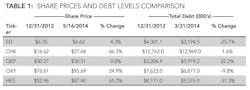

Three of the companies recently targeted by activists, including CHK, SD and QEP had debt that exceeded the 45% threshold. The other three, including HES, OXY and MUR did not have as high a debt load, but did have relatively large sums of cash (especially OXY with $3.8 billion at Sept. 30, 2013).

Activists have taken their pursuit of profits beyond the oil and gas industry, as cash is as good as money and it looms large in the eyes of potential activists. With nearly $150 billion on the balance sheet at Sept. 30, 2013, Apple (ticker APPL) looked like low hanging fruit. In October 2013, Icahn published a letter to Apple CEO, Tim Cook, disclosing the activist had purchased 4.7 million shares of the company, or approximately 0.5% of shares outstanding. In his letter, Icahn demanded Apple increase its approved plan to repurchase $100 billion of stock by 2015 to $150 billion.

On Sunday, Feb. 9, 2014, Institutional Shareholder Services recommended that shareholders vote "no" on Icahn's plan. Interestingly, the previous week Cook told the Wall Street Journal that Apple had accelerated its planned purchases, and had repurchased $14 billion ahead of its annual filing, much of it (approximately $8 billion) from institutional investors.

Cook effectively did what Icahn was demanding, and put enough cash into the hands of investors to cool their enthusiasm for the Icahn plan. Consequently, on the next Monday Icahn withdrew his demand. Cook may have ostensibly won this round, but Icahn is hard to get rid of. Oil and gas executives can learn from this example of proactively managing an activist initiative from the technology industry.

For the companies that did not have a debt-to-market cap that exceeded the threshold, they came under scrutiny for lackadaisical share price performance and/or having a large cash cache. Liquidity is needed in a cyclical and capital intensive business, but how much is too much? The answer to that question depends on a company's growth plan, but Occidental's $3.8 billion cash treasure chest was more than enough to attract the unwanted attention of activist First Pacific Advisors.

Keeping activists at bay is not the only reason for maintaining financial flexibility and a conservative balance sheet. Keeping debt low and cash reasonable are prudent things to do in a cyclical industry that can also exhibit volatility.

Compensate on performance

Lucrative compensation plans are sure to attract attention, especially if shareholders have not profited along with management. First Pacific Advisors noted in their public letter of April 11, 2013, that the top two executives at Occidental were paid a collective $640 million in estimated total compensation since 2000.

FPA's letter also mentioned that the average board member compensation was approximately $640,000 annually, the fifth-highest board compensation in the S&P 500 at the time. Is this compensation "excessive?" Shakespeare was right, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and someone at FPA got enough shareholders to see "ugly" in OXY's management and board compensation plans, which led to the departure of then CEO Raymond Irani.

Fig. 2 illustrates the indexed stock price performance of the E&P companies that have drawn the attention of activists in 2013. All of the stocks targeted by activists in this analysis underperformed the S&P 500 and all but two, have underperformed oil prices (near-term futures for WTI). More than one factor drove market reactions to the stocks, but regardless of the reason(s), equity prices that lag common benchmarks invite scrutiny. Activists viewed these stocks as undervalued relative to their intrinsic value.

If we consider the criticisms levied by FPA against OXY and if a picture is worth a thousand words, then the chart says it all. In the 15 quarters ended Sept. 30, 2013, OXY underperformed both the S&P 500 and generic oil prices. It is difficult to justify generous compensation for management and the board when shareholders are not winning. Since FPA's activism, the price of OXY equity has risen.

Buy some stock

When insiders buy stock, they are signaling that they are in it for the long run and believe in the company's long-term prospects. First Pacific Advisors noted that neither management nor board members had purchased any Occidental stock and as a result their interests were poorly aligned with shareholders. We have yet to determine if there is an ideal level of insider ownership that is perceived to align management's interests with those of equity owners, but there is something to be said about company holdings making up a large proportion of an executive's net worth being a strong form of motivation.

Activist redux

The first quarter earnings season has come and gone, and now is a good time to evaluate the results of activism highlighted in this article. In Table 1, share prices and debt levels are compared before activists made their presence known and at the end of the first quarter of 2014, after the market had had time to digest the results of activist influence. In three out of five cases, shareholders realized double-digit share price increases.

Some concluding thoughts

Investors have learned that although activists may be impolite, crude, and about as welcome in the boardroom as a skunk at a garden party, they serve a purpose and can make money for everyone. As more funds flow into activist funds, we are fully aware that if anything, activists will become, well, more active. That has some important, and even beneficial, implications for E&P management teams and boards.

We have yet to meet an executive who believes his or her company is fairly valued, and the day someone begins to feel that way is the moment when a company becomes vulnerable. The best way to avoid complacency is for executives to act like internal activists and do what is natural for good managers. Constant striving to overcome limitations, expand horizons, create value, and grow is the natural state of effective people, leaders, and board members. We expect activists to continue making headlines, so before one shows up on your doorstep, give us a call.

About the author

James Constas, managing director at EnerCom Inc., has more than 23 years of professional experience, primarily in oil and gas, in consulting, management, marketing, finance, economics and investor relations. He received his BS in International Management from Arizona State University and an MBA in Finance from the University of Denver. He is a member of the National Association of Petroleum Investment Analysts.