Managing reserves and resources

Efficiently overseeing a company's petroleum reserves and assets requires technical as well and economic and financial expertise

J. C. Rovillain, Enhanced Value Recovery (EVR), Houston

Imre Szilágyi,Exploration geologist and petroleum economist, Budapest, Hungary

Exploration economics, this "strange mixture of engineering economics, mathematics and statistics, probability theory and the more normal sciences of exploration – geology and geophysics" has made a lot of progress since defined by Robert E. Megill in his Introduction to Petroleum Economics. The newest Petroleum Resources Management System (PRMS) reveals some of the latest improvements. However, oddly enough, some mathematics, statistics, probability theory, and finance seem to have been all but left out of the economics equation of such a management system.

The challenges faced by E&P companies in their never-ending quest for renewed reserves, not to mention their production projects, have continued to grow exponentially. All make it only natural that the US Securities and Exchange Commission would welcome the introduction of modern financial forecasting methods. Some sophisticated stakeholders and stockholders are already welcoming advocated additional disclosure.

Uncertain reserves and resources

Ultimately, the fate of oil and gas companies rests on two pillars: their ability to assess, recover, and renew their reserves as well as their ability to produce said reserves in an economically sustainable fashion.

As a super-major learned the hard way roughly 10 years ago, genuinely doing your best and accurately reporting reserves goes a long way toward managing expectations surrounding risky investments as well as mitigating investment risk and fostering investor relations. Unrelenting efforts since that time by, among others, the SPE and SPEE should be commended in terms of better reporting and assessing reserves.

Applauding its latest enforcement program, the authors believe the SEC could go even further in terms of reserves disclosures "to protect investors, maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets, and facilitate capital formation." Consider this:

- The PRMS itself does more in terms of "economic risks" than the SEC guidelines when defining probabilistic estimates: whereas the PRMS includes critical economic data, the SEC Modernization of Oil and Gas Reporting "revised the definition so that it does not include the application of a range of values with respect to economic conditions because those conditions, such as prices and costs, are based on historical data, and therefore are an established value, rather than a range of estimated values." The SEC should adopt such a PRMS approach.

- The prevailing guidelines leave the door open for misunderstandings for those unfamiliar with the background mathematics, geology and/or reservoir engineering. Oil and gas reserves are generally approximated thanks to a random variable with a lognormal distribution. Combining the latter with a practice which seems to consider probabilistic P90, P50, and P10 with the respectively Low, Best, and High Estimates in a deterministic context equally good sets the stage for "methodology dependent" 1P, 2P, and 3P disclosures. It might well be the interest of resource evaluators and auditors, analysts, regulators, and investors to find an unequivocal resource volume figure; and quite another one which describes the measure of uncertainty of the estimations, ideally both properly quantified in terms of dollars as well. Additional significant mathematical and semantic oddities may need to be addressed as well.

- With "proven reserves" subject, among other parameters, to "existing operating conditions" that include "operational break-even price," any given proven reserve within a reservoir should vary (sometimes widely) based upon economic factors alone, i.e. even when estimated quantities would remain unchanged in between. Additional granularity regarding different types of economically recoverable reserves should be considered for more accurate disclosures and valuations.

- The reported oil and gas reserves are experts' estimates and any estimate carries uncertainty. Both "a priori" (i.e. prior to field development) and "a posteriori" (i.e. after the completion of field development) resources remain estimates. Although uncertainty decreases with maturity, the volumes pertaining to the different probability categories, including P50, may – sometimes relevantly – differ. The natural consequence is that proved and probable reserves (2P) of the very same accumulation will be different in the undeveloped and in the developed status, even if conditions regarding commerciality remain unchanged. Regulators, in their attempt to protect investors from disappointments caused by reserves write-off, pursue oil companies to apply certain "conservativism" in their resource assessment and reserve disclosure. The attempt seems to fail to reach the desired goal and can result in estimation biases.

The implications of the elements aforementioned are not only theoretical or academic. The SEC and PRMS seem to limit the disclosures and methods, with a notably skewed bias towards "insiders" and some highly sophisticated investors with advanced knowledge of reporting intricacies. Moreover, since reserves and resources are the lifeblood of this sector, in addition to the reserve-based finance (RBL, VPP, etc.) methodologies relying on…reserves estimates, all oil and gas financial matters are at least in some way indirectly connected to them.

It might be worth recalling that typical American and foreign stockholders do exist and that institutional investors have been investing for quite some time now into significant stockholdings of oil and gas companies, big and small. "Big Oil" could as well find it in their interest to work towards some more modern forecasting and reporting methods with a goal of reaping some additional returns opposite to their increased "commercial risks."

Risky investments

Technically speaking, the first modern commercial well in Titusville, Ohio eventually succeeded. Now, it had certainly more to do with implausibility and Knightian uncertainties than probabilities and Drake ended his life a pauper.

The use of probabilities has made improvements possible and helped sustain this industry. The fact that they are still used some 150 years later is a testament to the difficulties associated with the characterization of reservoirs, the uncertainties still pertaining to reserves, and to the risky investments and hard decisions that oil and gas companies have had to make. Two examples illustrate this quite well:

- On the exploration front, the US shale reserves are not yet deemed "reasonably certain" by leading experts, and

- the lag between upfront investments in big projects and their actual dollar outputs is but one illustration of the risky nature and the "optimism bias" plaguing the production end of the business.

Regarding the technical side of the business, much time, effort, and money have been devoted to geophysics, geology, engineering, and varied technologies to mitigate the risks of dry wells, boost production, etc. In short, as pointed out in a recent Wall Street Journal article, if you combine what Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Shell spent in 2013, the costs equal roughly the same "in today's dollars as putting a man on the moon." Moreover, the article suggests that "the three oil giants have little to show for all their big spending." Without further explanation, the article adds that "one of the biggest problems" is that "costs are soaring."

Even at historically high oil prices, new developments (CAPEX for 2014 projected north of a whopping $700 billion) could be cancelled or delayed due to actual project executions. Expenditures are nonetheless expected to more than double compared to the preceding five-year period. Notwithstanding, this and other news suggest that costs/investments are viewed favorably within the industry. Meanwhile, other reports tend to focus more on latest lackluster results as well as on the current project portfolio mix.

There is indeed more to the exploration and production business than what some petroleum engineers would prefer to believe. Less or inadequate attention and resources have been given in their management systems to cover the economics and the underlying financial mathematics. The so-called "commercial risks" deserve a closer look. They go beyond the discrete P10/P50/P90, NPVs, hurdle rates, and Swanson formula.

Two well-written chapters inside the 2011 PRMS Guidelines are certainly a step in the right direction. Now, since the authors are not privy to how advanced the use of commercial and financial mathematics actually is within each and every oil and gas company, the authors manage to remain confident (and certainly hope) that none of these companies stops their commercial and financial analysis there.

Investment risks

Investment risk can take many forms and affect companies of many different sizes. Apart from direct or disguised expropriation (certainly a part of the investment risk relative to petroleum resources), tax optimization has been an integral part of the management system of petroleum resources at least since the interesting negotiations with King Ibn Saud in the 1930s. The increased sophistication of fiscal terms has helped facilitate a better understanding between countries with their hard currency providing guests, a.k.a. IOCs.

Another form of investment risk can be illustrated by way of a recent development as described in the WSJ article previously mentioned: "The spending surge has drawn attention from US securities regulators, who have demanded more disclosure from Chevron as to whether the jump will get even bigger and affect the company's liquidity." Chevron told regulators it "will provide more details." One has to hope that Chevron's shareholders and stakeholders will now get some of the answers they rightfully deserve.

Portfolio asset allocation comes to mind when mentioning investment risks in addition to the obvious investment risks stemming from the sheer size of some of the biggest projects. In other words, the higher costs associated with finding and developing oil fields is not the only culprit. The solution need not necessarily exclusively come through lowering CAPEX budgets, morphing CAPEX into OPEX or from further (costly) advances in energy technology. Strategies already followed by a few suggest that quantitative tactical asset allocation can provide risk mitigation and/or better risk-adjusted returns.

Unfortunately, when all sorts of mathematics are used on the technical side, some reluctance towards quantitative techniques seems to remain on the commercial end, not to mention a virtually non-existent PRMS financial risk side.

Considering that the set of reserves and resources oil and gas companies possess is increasingly varied, that the PRMS mentions aggregation (with some computations), and the SEC and the PRMS guidelines refer to each other, ignoring the "portfolio effect," this just makes less and less sense. The authors' understanding is that the testing of some senior managers holding such knowledge would have prevented them from sharing any of the formulas intended for audiences who usually are not able to understand them.

Some recent statistical/ stochastic methods and uncertainty concepts such as why no "exact" number can "just" be given, active portfolio management and/or nonlinear option pricing could certainly be worth a (renewed) look. All in all, more elaborate mathematical finance techniques and solutions should now take more room inside the Big Oil tool box and be applied when big-bet strategies drain cash piles and mandate buying back fewer shares.

Investor relations

As part of their duty of pleasing their owners, oil and gas companies might consider justifying more thoroughly at least some of their investments, risks, and decisions pertaining to their business via different forums, investor relations departments surely included. More widely sharing information, even reluctantly, could prove helpful to those companies for several reasons:

- Remembering that Graham and Dodd's Security analysis, "a roadmap for investing that I have now been following for 57 years" (Warren Buffett), states, "It is a notorious fact, however, that the typical American stockholder is the most docile and apathetic animal in captivity" won't provide help under the present circumstances.

- Employees are stakeholders and sometimes shareholders as well via their 401k plans.

- Institutional investors have already shown they have choices in terms of the stocks and the sectors they want to overweight and underweight.

- The financial sector at large could look at the industry with kinder eyes (and consequentially lower fees) if they perceive it as less risky, i.e. more predictable. Now, the data provided might need to be more directly actionable, readily accessible and at times forthcoming to make better-informed decisions.

It has been well documented that private investors and financial market participants (bankers included) hate outliers, a.k.a. "surprises," and it is not unheard of that "risk premiums" are attached to the latter. Moving forward, this could be not only the right thing to do, but the smart thing to do, potential/actual big project roadblocks included.

The latest profit warnings have been an additional unwelcome surprise to investors and may be a symptom of a wider trend. Some room for improvement could exist at Big Oil (investor relations included) at a time when WTI and Brent have more than doubled within the last five years and the SPDR S&P Oil & Gas Exploration & Production ETF has "jumped" less than 20%. Even taking into account other underlying factors in terms of individual stock performance, it is notable that relative newcomer Google's market capitalization has been neck and neck with ExxonMobil's, and no oil and gas company is likely to approach that of Apple anytime soon.

Some additional non-technical risks, e.g. environmental risks and/or actual incidents, may be less directly quantifiable, legal fees included. They nonetheless rarely fail to "transpire" in the arena of public opinion and on the stock market, including in terms of the overall E&P risk reward ratio as perceived by investors, particularly when compared with other industries. A broader view suggests that another kind of activist other than environmental may speak louder in the future, namely activist investors.

Summary and conclusions

As far as reserves and resources are concerned, significant progress has been made on the technical side. Less has occurred regarding the commercial, financial, and financial markets sides of the business even if the past PRMS has been a timid first step in this right direction.

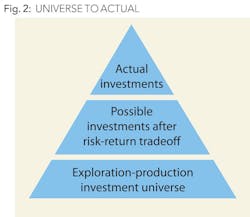

Reserves and resources production are the cornerstone of the entire oil and gas industry. Now, only two ways exist for companies encompassing actual E&P departments to add/renew reserves and be viable in the long run: 1) an appropriate, i.e. competitive, portfolio management of their existing and potential future assets, e.g. quantitative asset allocation, and 2) significant purchase of competitors' reserves through Wall Street. Some volatility as well as changes/transitions in strategy may be expected, and as before, only the fittest survive.

Let's face it. It is not the nature of the business that gives oil and gas companies an image problem and an investor issue. In addition to relying on their technical expertise, oil and gas companies will gain and/or sustain a competitive advantage within their industry by providing additional actionable information to stakeholders and shareholders (e.g,. accuracy, granularity, and economics regarding reserves, resources and projects); and by better managing and mitigating the commercial and investment risks pertaining to their exploration and production, thanks to advanced quantitative portfolio and finance techniques.

About the authors

Jean-Christophe "J.C." Rovillain is a managing consultant at Enhanced Value Recovery (EVR), a private consultancy. Previously, he spent more than 10 years with various companies related to the financial markets, including Dow Jones and BARRA. He holds an MS degree in financial markets and investments from the KEDGE Business School. Rovillain also serves as an executive vice president at LEXIPRO and is a member of SPE, USAEE, and NOMADS. He can be reached at [email protected].

Imre Szilágyi is an independent exploration geologist and petroleum economist based in Budapest, Hungary, and is a frequent contributor to Oil & Gas Financial Journal. Having gained industry experiences as a senior and line manager with a mid-size operator, he current runs a private exploration business consultancy. Szilágyi holds an MS degree in geology from Eötvös Loránd University and an MBA from Budapest University of Technology and Economics. He can be reached at [email protected].