Organizing for success

Designing and enabling a successful land organization

Reid Morrison, Steve Wright, and Richard Rose, PwC, Houston

Nowhere has the impact of US onshore resource play development been felt more strongly than among land organizations. The volume and pace of development within resource plays requires faster, more "nimble," and more capable land organizations than in the past. The strategic importance of land has been elevated, but E&Ps are only now beginning to assess their land organizations holistically to understand what success looks like and how they can enable that success.

Drawing upon PwC's Land Benchmarking Study and interviews with more than 70 oil and gas professionals from different functions across 20 E&Ps, we outline in this article a framework for understanding what success looks like within land – we detail what the renewed strategic importance of land means for operators in terms of organization, people, and process. Together with exploration and development, land is one of the critical planks for a successful upstream operator.

The strategic importance of land

Land is one of the few functions involved across the entire asset lifecycle (see Figure 1).1 The strategic importance and complexity of land, with all of its underlying legal, regulatory, and financial elements, has often gone unnoticed by E&Ps, which are predominantly run by professionals with geoscience or engineering backgrounds.

Without a well-functioning land organization drilling activities can come to an abrupt halt and operators can also face significant legal and financial risks from title defects, lease or royalty compliance or other issues. Conversely, an effective land organization enables acquisition and divestiture "nimbleness," efficient rig deployments and movements, and risk (lawsuit) mitigation.

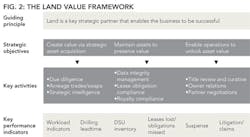

Although overall success depends upon each operator's size, geography, and strategy, land plays a key role in delivering value to the organization. The land value proposition is composed of three value pillars (see Figure 2):

- Creating value through the strategic acquisition of assets,

- Preserving value through the maintenance of those assets, and

- Unlocking value by enabling the exploitation of those assets.

How should land be organized to deliver on its value proposition? Should land operations and land administration be embedded within an asset/business unit or should they function as a central unit? To whom in the organization should Land report? How should resources within land be organized?

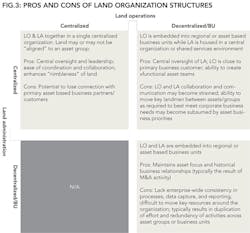

Organizing your land department

There are a variety of ways to organize a land department, and each company does this slightly differently – most varying in the degree to which they are asset-based versus activity-based. Historically, it has been common for land administration to be organized functionally (often reporting to legal or finance), while the land operations group is embedded in the asset. An important finding from our research is that land organizations are most effective when they are centralized (reporting to a single entity) but still connected to the assets, with strong links between land operations and land administration (see Figure 3). This structure encourages the advancement of both asset-specific knowledge and functional excellence.

Whatever structure is chosen, it should be designed with workflows that not only address difficult linkages and handoffs, but enhance coordination and communication among land operations, land administration, finance, legal, and other interfacing business functions. Despite the strategic, connected role of land operations and land administration, many organizations have split the two into wholly separate functions, thereby failing to engender the coordination, cooperation, and trust between those functions that is vital for land success.

For all but the smallest E&Ps, one important step to achieve all of the outcomes cited above is alignment of land operations and land administration under an identified land leader, typically an executive or vice president of land.

The benefits of functional alignment under a VP of land

The single greatest indicator of a successful land organization in our study was a strong executive leader. In the absence of a single organizational leader, problems can arise in a host of areas: strategic direction, coordination and communication between land operations and land administration, resource management, and even career development. The benefits of common discipline in processes and management far outweigh any potential challenges.

Specific benefits of aligning Land Operations and Land Administration under a single leader include:

- Strengthening communication lines across the organization: Separate leaders for land operations and land administration can create significant communication gaps between the groups. A single leader can close that gap and provide a unified strategic vision for land—one that fosters collaboration, and mutual respect. In the event of issues that arise between land operations and land administration, a strong VP can act as an arbiter or referee. Results from PwC's 2014 Land Management Benchmarking Study also indicate that a single land organization leader strengthens communication and data flows across the Land value chain (see Table 1).

- Enhancing visibility and recognition of land: An executive leader commands a greater seat at the table for land. A VP is positioned to provide the rest of the organization with insight on the importance and complexity of land, and the strategic land implications of their actions. Greater visibility of land promotes a greater understanding, respect, and willingness to collaborate with and across the entire organization.

- Promoting consistency in processes across geographies: Consistency enables organizations to leverage the full power of land systems. Inconsistent processes and policies not only result in re-work and high error rates but present business risks. Consistency results in greater efficiency and accuracy in processing work (e.g., leases, rights of way). Standard processes also enhance trust between land operations and land administration – roles and responsibilities are clearly defined, expectations clearly set, and there is a single source of the truth for land information and data.

- Ensuring staffing meets the needs of the entire business: In the absence of a single leader, inefficient utilization of land resources often occurs. Each asset group leader has an incentive to hoard valued resources even if they may be needed more elsewhere in the organization. A single executive leader can ensure that workloads are balanced, key projects are prioritized, and the right resources are assigned to the right roles.

- Hiring, retaining, and developing top land talent: Without a land organization leader, the career path for a junior lease analyst or land technician can appear stale. New recruits are looking for more opportunities and experiences than previous generations – the 30-year career lease analyst is a thing of the past. A strong VP promotes the development of varied career paths and ladders and the necessary performance management practices to both ensure high performance and provide feedback to employees.

Measuring the value of land

Although some E&Ps are beginning to recognize the importance of a unified land organization, in most cases they have yet to measure the value that land can bring to the company. More than a third of the companies we interviewed did not utilize any key performance indicators (KPIs) to manage the land organization; more than half had no metrics at all specific to land operations performance.

Companies that attempt to capture performance typically rely on workload metrics (e.g., leases or owners set up per month) or activity measures (e.g., leases mapped or obligations met) at the individual, not departmental, level. In Figure 2, we suggest some performance measures that can provide visibility into land performance and allow for timely corrective action if needed. These measures are not currently applied widely in the industry. Specific recommended measures (and the intended value they capture) include:

- Drilling lead time: How far in front of scheduled "ready-to-spud" date is land? Increasing lead time increases drilling flexibility and decreases incidence and days or rig downtime, ensuring that production targets are met and costs are minimized.

- DSU inventory: How prepared is land for changes in the drilling schedule? As with drilling lead time, increased inventory means increased flexibility and decreased delays.

- Trade/swap value: Capture the activities conducted and estimates of the value captured. Not a traditional ongoing metric or KPI, but important to track and promote the importance of these value-enhancing activities. The increased lateral lengths and working interest percentages brought about through better trades and swaps are particularly important for horizontal drilling.

- Leases lost or obligations missed: Identify both the acreage and value lost and the cause of the error. Tracking these over time will allow you to perform root cause analysis and identify necessary improvements.

- Litigation/claims: Track issues, causes, and outcomes over time. The key is to leverage information on claims to identify root causes and implement improvements, with the goal of reducing the occurrence and extent of future claims.

- Suspense: Track and manage suspense levels to identify causes for changes and determine necessary improvement steps.

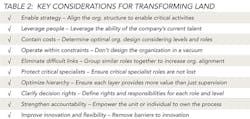

Transforming and building a single land organization

Changing operating models is never an easy task, but transforming to a single land function—with unified policies and procedures, a single source for data and reporting, and a cohesive strategy for identifying, acquiring, retaining, and developing land talent—can yield tremendous value (see Table 2 for key steps).

To transition toward a single land organization, companies may also want to consider creating a land center of excellence (COE). The land COE accelerates the application of uniform processes, standards, and forms, and helps institutionalize data quality standards, controls, and updates. The COE should also coordinate land functional training, technical skills development and career path mapping (e.g., asset rotation programs). Finally, a COE should oversee and prioritize land special projects and initiatives, which can collectively present a great resource strain if not managed properly. Finally, to ensure that changes are successful now and in the future, companies should not only train current staff but also attract and retain top talent. Strengthening talent management practices should position land organizations to differentiate their "brand" among new recruits and reduce the costs and business risks associated with turnover of land personnel. Thinking strategically about talent acquisition, development, and retention can not only help your organization to be successful today, but it will lay the foundation for success into the future.

About the authors

Reid Morrison leads PwC's US advisory energy practice. He has 22 years of consulting experience, primarily focused on the energy industry, centered on developing and "operationalizing" strategies to increase revenue and decrease costs.

Steve Wright is the oil and gas benchmarking lead at PwC. He has more than 25 years of experience in benchmarking and applied research. He has developed and led industry studies on cost management, operations, supply chain, finance, and human resources.

Richard Rose is a member of PwC's energy advisory practice in Houston. He focuses on assisting upstream oil and gas clients build efficient and effective land departments. He has assisted clients with organizational design and strategy, business process improvement, land and lease management system implementation, M&A integration, and departmental strategy/decision making.

1References to "land" throughout the article include both the land operations and land administration functions, unless otherwise noted. Land operations activities are primarily focused on acquiring land and mineral rights (via landmen), conducting title review and curative, and managing field brokers, and land administration activities are primarily focused on documenting and maintaining records associated with leases, contracts, ownership, joint operating agreements, etc.