Growing pains

Current trends and likely results of North American LNG export initiatives

Kevin Keenan and Lindsey Blankenau, Baker Botts, Houston

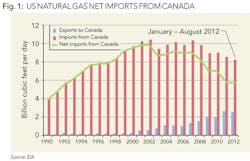

From 1821 to 1957, U.S. domestic natural gas production roughly equalled demand. In that year, the US began a nearly 50-year period of Canadian natural gas imports, with net imports peaking at over 10 bcf/day in 2002. Over that period, Canada found in the US a market hungry for natural gas exports and the US found in Canada a stable source of natural gas imports to augment its own domestic production. That trend began to decline in 2002, with a sharp drop beginning in 2007 as a direct result of US domestic production from shale and other tight gas formations (Fig 1).

The development of economically feasible ways to produce marketable quantities of natural gas from previously inaccessible shale and other tight gas formations has led producers on both sides of the border to explore overseas markets as they retool to monetize the significant surge in production. Begun almost 10 years ago, the shale gas revolution is no longer breaking news, but the effects of this shift have yet to be fully revealed and so it is intriguing, at least, to explore where we are likely headed.

On the surface, one might be tempted to say it's no big deal. The US will soon produce enough natural gas to meet domestic demand and can (arguably should) export the surplus. And Canada, already comfortable with exports from a policy standpoint, can (arguably should) turn its attention to other markets - larger markets in Asia, for example - as an outlet for gas already tagged for export. But it's never quite that simple. Change is difficult, often doggedly slow and always expensive. This article discusses some of the challenges and opportunities faced by US and Canadian natural gas exporters in light of the difficulties, the pace and the expense of this massive retooling effort.

The difficulties

United States

Shale gas production has opened a vigorous public policy debate in the US. While exporting US natural gas could provide many benefits, including tipping the balance of payments slightly back in its favor by decreasing its negative trade deficit, industrial users of natural gas are concerned that the benefits will be outweighed by increased domestic natural gas prices. Because low natural gas prices could herald a manufacturing renaissance in the US, upward price pressure due to exports, and its potential to curtail that renaissance, is the crux of the issue in the US public policy debate.

Canada

The enormous production shift in the United States alongside new Canadian shale gas production can only exacerbate the potential surplus situation in Canada by adding new production to the significant level of existing production that is rapidly losing market share south of the border. Moreover, Canada finds itself in a situation, having a land border with but one country, where switching to new markets means largely retooling much of its transportation infrastructure to access those new markets. Where Canada's gas export infrastructure relied exclusively on cross-border pipelines for more than 50 years, Canadian exporters must now build liquefaction facilities to produce and load LNG onto ships for maritime transport. To feed the majority of those liquefaction facilities, they must build new pipelines across the Canadian Rockies to bring natural gas from producing fields in Alberta and the interior of British Columbia to the Pacific Coast. And those pipelines must cross ancestral First Nations lands en route to the sea.

Generally, First Nations have opposed these projects. While there remains considerable opposition, ground-breaking agreements have recently been signed with affected First Nations that many believe will open the door to the multiple agreements that will ultimately be required to enable project sponsors to reach a final investment decision (FID). These agreements signal a willingness on the part of project sponsors, First Nations and the BC provincial government to seek common ground and, most importantly, to share in the potential upside of these projects - a critical component in their success.

The pace

As of July 18, 2014, fourteen proposed LNG export terminals in the United States and three in Canada await approval from federal regulatory authorities in Washington and Ottawa (Fig 2). Twenty-five additional sites are listed as potential projects (Fig 3). On July 30, 2014, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approved construction of Freeport LNG Development LP's LNG export project, making it the third US project to receive full FERC approval.

United States

The United States is the world's second largest producer and consumer of energy, and has been a net importer of energy for the past 62 years. While the US has exported hydrocarbons for years in quantities dwarfed by its level of imports, and while those exports have largely been refined petroleum products, large-scale exports of raw hydrocarbons poses policy questions with which the US has not grappled for more than two generations. As a result, the US has struggled with the export approval process.

For gas exports, the United States has a multi-step approval process. The DOE issues permits to export LNG to countries with which the United States has free trade agreements (FTA permits) and to all other countries (non-FTA permits) in accordance with Section 3(a) of the Natural Gas Act (NGA). If the order is "consistent with the public interest," FTA permits must to be granted "without delay." The same "without delay" directive is not present for non-FTA permits, and the DOE has taken far longer to approve these permits, including, beginning in mid-2011, imposition of a temporary hold pending the results of the EIA/NERA studies. Having subsequently lifted the temporary moratorium, as of August 1, 2014, the DOE has granted non-FTA permits to seven projects. Additionally, US export projects must secure an environmental impact assessment and an authorization to construct from the FERC. Currently, the DOE and FERC review each application individually in the order it was received. This allows each project to be carefully evaluated, but is also arguably cumbersome and time consuming. Notwithstanding the DOE's early delays, on May 29, 2014, the DOE proposed revisions to the application procedure for non-FTA permits. The principal revision is the elimination of conditional approvals; the DOE now proposes to make final public interest determinations only after completion of the environmental review process, irrespective of the applicant's position in the overall application queue. The goal is to create a more efficient process that will evaluate commercially mature projects in a timely manner.

Prior to the DOE's unilateral revision of non-FTA export review procedures, new legislation was introduced to address perceived procedural inefficiencies. On April 30, 2014, the House Energy and Commerce Committee approved the Domestic Prosperity and Global Freedom Act, which was subsequently amended to (i) require a final DOE approval decision within 30 days after completion of the environmental review process, (ii) provide for expedited judicial review by the US Court of Appeals for the circuit where the export facility will be located, and (iii) require public disclosure of export destination as a condition of export authorization approval. As amended, the Act was passed by the House on June 25, 2014. It is unclear how this legislation - and its prospect for final enactment - will be impacted by the DOE's overhaul of its own procedures. On the one hand, the legislation goes considerably further than the DOE's proposed changes. On the other hand, the DOE's overhaul does indeed improve the process considerably and might be enough to allay the sponsors' concerns and those of the bill's Congressional supporters. Regardless, both offer a clear signal of broader governmental support for US LNG exports.

Canada

Canada is the world's fifth largest producer and the sixth largest consumer of energy. With Canada's energy sector already accustomed to operating squarely on an export footing and with public opinion and public policy already aligned with that export-friendly bias, Canada has implemented a streamlined process for reviewing LNG export licenses.

Canada's National Energy Board (NEB) issues LNG export licenses in a process that involves a fixed beginning-to-end time limit of 18 months for most NEB applications, strict guidelines as to what must be considered during the process and the ability to review multiple licenses simultaneously. As of August 1, 2014, the NEB had approved eleven export permits and was reviewing nine additional applications. Once a project receives its NEB export permit, it enters the environmental assessment (EA) process, a process overseen by the NEB in cooperation with the relevant provincial government. Additionally, on a provincial level, West Coast projects must be granted a facility permit from the BC Oil and Gas Commission before construction begins, while East Coast projects in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick must be granted a Permit to Construct from the Nova Scotia Utility and Review Board or an Approval to Construct and Operate from the New Brunswick Department of Environment and Local Government, respectively.

The expense

United States

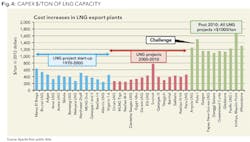

Once a project has secured the necessary approvals, there are still significant commercial hurdles before FID can be taken. In the US, Sabine Pass LNG is currently under construction and Cameron LNG is likely to begin within the year. In Canada, as of August 1, 2014, not a single project has reached FID. Although US/Canadian natural gas feedstock is relatively inexpensive, the cost of LNG export projects worldwide has increased dramatically in recent years (Fig 4).

On a tonnes per annum (tpa) basis, greenfield US LNG export terminals are projected to cost between $700 and $1,000/tpa, with brownfield terminals expected to cost approximately $462-660/tpa. Add to that the cost of supplying gas, and a US project could reach +$2,000/tpa for a 20-year project life.

Canada

Costs in Canada are projected to be higher still, with some estimates around $1,200/tpa for facility costs alone, due to the largely greenfield nature of the projects, higher labor costs in Canada, and the environmentally sensitive nature of the region. Additionally, uncertainty about long-term pricing and other costs have stalled FIDs for Canadian projects.

Both countries

As US and Canadian export projects move toward FID, costs will ultimately be prohibitive to some, and those projects will not go forward. Other projects might suffer the effects of uncertainty surrounding pricing, long-term stability of markets and other factors.

Of the seventeen US and Canadian projects listed as "proposed" above, one thing is certain: not all will be built. Capital markets, as but one factor in determining which projects will succeed, will support the completion of only a fraction of the proposed terminals. When determining which proposed projects will see completion, it is generally accepted that brownfield terminals have a cost advantage over greenfield sites, although the likely result will be a mixture of the two. From a free market perspective, we can only hope that it is costs, prices, markets and access to capital (rather than stifling regulation and crippling delay) that determines which projects are viable and which ones are not.

The result

So what are the likely results of this massive infrastructure overhaul? One answer is that these terminals may be exporting their capacity to overseas markets at a cost advantage to international competitors. But even that is uncertain. While many of these projects have already entered into long-term LNG offtake agreements with a number of overseas buyers in Europe, the Middle East and Asia, these agreements are contingent on final regulatory approval and FID. Meanwhile, Russia's Gazprom signed in late May a long-term agreement to supply China with $400 billion of pipeline gas at $10-11 per million cubic feet (mcf), a transaction that could impact Asian demand and, as a result, exert downward pressure on prices for US and Canadian LNG in Asian markets. The China sale is clearly, in part, a hedge against the possibility of decreased future exports to Europe, which consumed nearly 18.7 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas in 2013, with Russia supplying 30% (5.7 tcf) of the total volume.

While there is an opportunity for North American LNG to displace some of Europe's dependence on Russian gas, there is no "quick fix" to Europe's energy issue. North American terminals will not begin to come online until late 2015, and much of the capacity has been contracted for shipment to Asia. Nonetheless, Europe will likely become a valuable market for US and Canadian LNG exporters as Europe seeks to decrease its dependence on Russian supply.

Change is never easy and the road to success for many of the projects in North America is fraught with difficulty as rising construction costs, access to capital, policy concerns, environmental opposition, rising labor costs, burdensome regulation, aboriginal opposition and even geopolitical events can, in the aggregate and in some cases individually, sink an otherwise healthy and viable project. Many of these issues have kept the pace of development sluggish. As export projects compete for markets and capital, the energy world - and in particular the LNG industry - watches intently to see if a new market paradigm emerges or if, as some have suggested, many of North America's exporters are already too late to the party.