Midstream goes mainstream

Opportunities abound for investors in MLPs, but caution is also in order

Stephen Morgan, Capital One, New Orleans

In 1986, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was on the rise, and analysts were confidently predicting that in the near future-as it turned out, in January 1987-it would break 2000 for the first time. In the meantime, the US Congress was busy forging a landmark bargain on taxes, lowering rates on ordinary income in exchange for higher capital gains taxes. The numbers would not add up, however, unless it also tightened up the corporate tax code.

This exercise led it almost inevitably to take a fresh look at master limited partnerships (MLPs). These partnerships avoided corporate taxation even though they traded publically like corporations-and the decade so far had seen them proliferate since Apache Corporation created the first MLP in 1981. Hotels and motels, restaurants, cable TV companies, amusement parks, and, most famously, the Boston Celtics, were all organized as MLPs.

With section 7704 of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, Congress closed this loophole by declaring that publicly traded partnerships should be taxed as corporations. It made two notable exceptions. First, existing MLPs like the Celtics were grandfathered in. Second, it exempted partnerships that earned at least 90% of their income from "qualifying sources," including interest, dividends, capital gains, and "from the exploration, development, mining or production, processing, refining, transportation ... or the marketing of any mineral or natural resource."

The goal of this legislation was to spur the development of domestic energy resources and stem the rising tide of imported oil sourced from politically unstable regions of the world. This exception was enacted with a sense of urgency as the US energy industry was suffering from a 50% collapse in the prices of oil and natural gas and an unprecedented number of bankruptcies.

It soon became clear that firms best suited for the MLP structure were midstream energy companies, entities that owned the infrastructure needed to store or transport oil, natural gas, and other forms of fuel. These companies are generally insulated from the volatility that affects revenue generated by upstream production or downstream production of finished products. As a result, these midstream companies produce the kind of steady, predictable cash flows that are ideal for MLPs, as cash distributions are based on an MLP's distributable cash flow, not its net income.

The Energy Renaissance: MLPs come into their own

For most of the 1990s and into the mid-2000s, MLPs occupied a quiet corner of the market. Then the Energy Renaissance began remaking the energy landscape. Domestic crude oil production is now back to levels last seen 25 years ago.

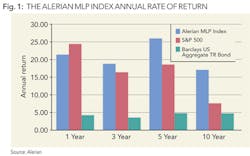

As more and more oil and gas moves around the country, the returns on midstream energy MLPs are quite naturally shooting up-and investors are taking note. The Alerian MLP Index shows a 17.3% compounded annual return over the 10 years ending with the second quarter of 2014. (See Fig 1)

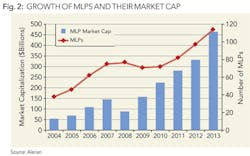

Just as exceptional has been the growth of the asset class itself. In 2004, there were 38 MLPs being traded with a market capitalization under $100 billion. By mid-2014, there were 116 with nearly $500 billion in market cap (See Fig 2). Indeed, 2013 was a banner year for new MLPs with a record 21 initial public offerings coming to market raising an also-record $8 billion.

With the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) projecting strong domestic oil and gas production for decades to come, this level of performance and growth is likely to continue. As new sources of production come on line and new markets come into view, there will be increased need for the infrastructure to transport both raw and refined products. Liquefied natural gas is a prime example. Just a few years ago, the United States was building infrastructure to accommodate imported natural gas. Now, new pipelines and storage facilities are being constructed to support natural gas exports. These new assets are ideal subjects for MLP ownership.

In a report earlier this year, the INGAA Foundation (formed by the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America) estimated that over the 22-year period from 2014 to 2035, $641 billion (or nearly $30 billion per year) in constant dollars would be required for investment in midstream infrastructure for crude oil, natural gas and natural gas liquids. Despite the remarkable growth of the asset class over the last 10 years, this forecast suggests that the demand for MLP funding will remain strong for some time to come.

As an additional potential source of growth, Congress is currently considering legislation that would expand the ability to use the MLP structure to a number of renewable energy industries, thus allowing a whole new set of companies to establish MLPs. Rather than limiting the kinds of "qualifying income," it appears that lawmakers may be inclined to expand them.

Growth prospects for MLPs are leading investors to refocus on their other advantages. First and foremost is the stability and transparency of cash flow from traditional, midstream MLPs. They have long-term contracts in which rates, rate increases, and even minimum volume commitments are carefully specified. These MLPs may also provide a hedge against inflation. They represent hard assets that should appreciate with inflation, and the use of a toll road model with tariffs often tied to inflation provides an explicit inflation hedge.

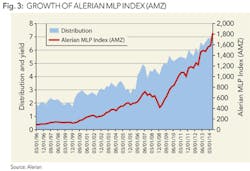

In this low-interest rate environment, investors also like their attractive yield. Unlike real estate investment trusts, MLPs are not subject to regulatory mandates to distribute a particular percentage of available cash flow, but the partnership agreements and investor demand, coupled with the absence of corporate-level taxation, encourage a healthy cash distribution. While overall yields for MLPs have dropped recently as prices for the MLP units have risen, they generally remain attractive compared to other income-generating assets. The fact that MLPs have the ability to grow their income, and with it their distributions, adds substantially to their appeal. Indeed, the growth in distributions has been a major driver of return. (See Fig 3)

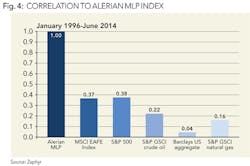

Finally, because MLPs have traditionally shown low correlation to both domestic and international stocks and bonds, they can provide investors with an important source of diversification. Perhaps even more importantly, they have shown low correlation to the underlying commodities, providing offsetting diversification for institutions and individuals with high commodity exposure. (See Fig 4)

New investors, new vehicles

The track record of MLPs over the last few years, their many advantages, and the estimates of future performance, have brought new classes of investors into the market. The traditional MLP investor was an individual, often an oil and gas industry veteran, who invested directly in the MLP units. Now, the higher yields and potential for diversification are also attracting small investors less familiar with the energy sector. For these investors, however, dealing with the tax treatment of MLPs-they receive K-1s not 1099s-can be a disincentive.

On the other end of the spectrum, institutional investors who may have avoided the asset class in the past because of liquidity issues are taking a closer look. For many taxable investors in this category, the special treatment of income is a major drawing point, allowing for tax deferral and other sophisticated planning techniques. Increased institutional participation, in turn, is particularly noteworthy because the prospect of access to the pools of capital these investors represent is fueling the creation of new MLPs and pushing market capitalization ever higher.

This diverse investor demand has inspired the investment industry to develop new platforms for investment. The index provider Alerian traced some of this history at a recent conference for the National Association of Publicly Traded Partnerships. The first closed-end MLP fund launched in 2004, followed by a series of innovations: the first MLP Exchange Traded Note in 2007, the first MLP mutual fund in 2010 and the first MLP Exchange Traded Fund in 2011. These pooled products provide diversification, ease, and simplified tax treatment.

At the end of 2013, there were a total of 48 such innovative products, representing $48 billion in assets under management. This is still well under 15% of the total market value of MLPs, but is clearly an area of rapid growth and represents an important constituency and source of liquidity for midstream companies. In addition, both hedge funds and professional managers overseeing portfolios of directly held MLPs have also become important participants in this market. Each of these vehicles offers different features and tax treatment, providing investors with greater flexibility.

MLPs as investments

While there are many reasons to invest in MLPs, there are several issues investors should consider before dedicating capital to the asset class. In recent years, midstream MLPs have been joined by MLPs based on upstream assets and refineries, exposing investors to volatility in commodity prices and in spreads between raw and refined products that will be reflected in distributions. If investors have a bad experience with these more speculative MLPs, the values of high-quality MLPs may also be affected.

There is also regulatory risk to consider, relative both to the tax treatment of MLPs and to the energy industry as a whole. There is always the possibility that Congress or the IRS might decide to eliminate special tax treatment, either directly or by putting new conditions on its definition of qualifying income. The IRS periodically calls a halt in its rulings to review this definition. It is also possible that efforts to reduce reliance on fossil fuels through such measures as a carbon tax will dampen the underlying growth of the oil and gas sector upon which so many MLPs depend.

Liquidity risk can be particularly acute for MLPs. Because they distribute much of their cash flow, many MLPs need to borrow to fund growth. If interest rates rise, this could become more difficult to do.

And finally, there are the usual caveats associated with partnerships. Unitholders in MLPs are typically limited partners and, as such, generally lack the voting rights afforded shareholders of traditional corporations. In addition, the general partners may have a special claim on the growth of distributions that leads their interests to vary in some ways from those of the limited partners.

All things being equal, however, the advantages of MLPs, the tremendous growth they have shown over the last decade, and their prospects for the future make them worth the consideration of any investor seeking yields, diversification, and differentiating tax treatment. At the same time, they are not risk free, nor are they as straightforward as they have been in the past. For investors new to this category, a good solution would be to seek professional management or turn to one of the new MLP funds and leave evaluation of specific MLPs to experts who understand their nuances.