Emergence of the new oil price paradigm

Adi Karev Deloitte Consulting LLP Washington, DC

Manas Pattanaik Deloitte Consulting LLP Houston

Ashutosh Ashish Deloitte Consulting LLP Houston

null

Has the world seen the last of sub $30/bbl oil? What is guiding the new crude price? Do we really know how to forecast or do we rationalize after the fact?

In today’s world of $70+ crude and the recent oil bust still relatively fresh, questions like these abound in the minds of the average consumers, companies that depend on oil for their business, nations across the world and the global intelligentsia. It would not be an egregious mistake if we rate energy and consequently oil price as one of the top topics in the world today at par with world peace and global warming.

While much has been said and continues being contemplated about the future direction of the oil price, this article focuses on the underlying factors that drive oil price. More precisely, we explore the changing global business dynamics of oil or what we call here the oil price “stakeholders” and their impact on the underlying price factors. We investigate how the underlying price factors have behaved traditionally and the departure from their traditional behavior responding to the changing global business dynamics of oil. We present the composite effect of this changed behavior of the underlying price factors and how that has prompted the movement towards a new Oil Price Paradigm.

The new Oil Price Paradigm discussed in the article does not predict a certain future price of oil but demonstrates the new ecosystem and equilibrium range in which the oil price is projected to reside. The article also presents the transitional behavior of the oil price as it shifts from its past equilibrium range to the new paradigm.

Historical and current trends

Before discussing the behavioral changes of the underlying oil price factors, let us explore the changing global oil business dynamics or oil price stakeholders that have spurred these changes. Growing demand from non-OECD countries, their increasingly active role in securing energy security to which their economic growth is tied, growing supply from non-OPEC producers, the greater role of national oil companies (NOCs) in the geopolitical arena and new E&P technology frontiers are the prominent changes in the global oil business today, to name a few. These changes can be reviewed primarily through three categories described below.

1) Market

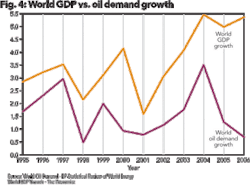

Demand in the western economies continues to chug along, while China shows no indications of slowing, or of faltering. Non-OECD Asia is expected to continue its annual oil demand growth at an average 2.7 % per year through 2030. Oil demand in other non-OECD nations is expected to range from 1.0% to 2.3% per year.

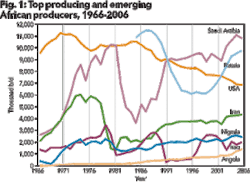

On the supply side, non-OPEC supply has risen every year since 1993, adding 8.3 million barrels per day between 1993 and 2006. Also, OPEC countries that the western world might be reluctant to deal with such as Iran are increasingly finding dedicated and committed trade allies in Asia. Sixty-five percent of the increase in world oil supplies between 2004 and 2030, i.e., 35 Mbpd, will come from OPEC countries while non-OPEC accounts for 35 % of this increase. As we can see, Russia, Iran, and Angola, and later perhaps Iraq, play an increasingly important role in supplying the worlds’ and particularly the Asian demand for oil.

null

null

2) Industry Structure

In the past 10 years the NOCs have learned that asset ownership alone is not enough to make substantial impact on the future of oil. The NOCs, once governmental corporations established to support the governments’ asset ownership are evolving into oil companies firmly based on the same economic principles as the International Oil Companies (IOCs) while keeping strong ties with their governments. In doing so, they are strengthening the ties between their governments and their business missions.

It is therefore getting less and less clear what is a political decision and what is an economic one. Few examples of this change in the recent years are events that have taken place in countries like Russia (e.g., Belarus, Yukos Oil, and Gazprom), Venezuela (re-contracting), Nigeria, Columbia, Chad (tax), and more.

3) E&P technology

The quest for higher efficiency, remote finds, unconventional energy and integration with downstream are some of the major emerging E&P technology trends today. Examples of these are evident in areas such as investment in deep water drilling, new seismographic endeavors, advanced reservoir modeling and remote collaboration centers. In addition, Middle East NOCs, which have traditionally focused on producing oil, are expanding their presence into the downstream by building new-age refineries that can handle heavy and sour crude they incidentally produce.

Emergence of these new technologies not only unleashes new frontiers for oil production but impacts the balance of power in energy ownership and consumption by bringing more countries from different corners of the world to have a stake in the oil business and/or an expanded value chain that includes refining and petrochemical complexes.

Historical oil price and new oil price paradigm?

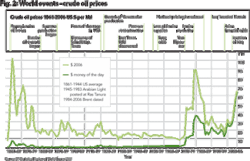

World events obviously tend to impact oil price. The question is, how do the changing global dynamics associated with these events affect the underlying factors that influence the oil price? To understand this more let us take a moment to review the historical oil price trend and some of the accompanying geo-political events depicted in Figure 2 below.

Historically we have seen several price spikes triggered by World events. It is noteworthy that the frequency of shifts in the oil price seemed to have increase after the year1970. The oil price range of $10-$20 per barrel (in 2005 USD) in pre-1970 era jumped to a range of $20-$30 per barrel (in 2005 USD) in late 1980s that continued until 1990s and into the first few years of 2000, after which there is again a shift in oil price in the recent years. What is also clear from the oil price chart above is that between the oil price equilibrium ranges such as the pre-1970 $10-$20 per barrel and the subsequent $20-$30 per barrel in the mid-eighties to the late nineties period, there are spikes and dips in oil prices. The steep price fluctuations during the 1970 – 1985 period and the one that we are recently witnessing (post 2003) are evidence to this.

There are two inferences that can be possibly drawn from the oil price movement in the trend chart. First, in the recent times, we are dealing with a higher degree of interactivity and coupling between global business dynamics and oil price compared to the earlier years. This may be due to an increased occurrence of geo-political events and willingness to make energy an embedded part of a country’s foreign and internal affairs. Second and perhaps more important to our discussion in this article, the underlying factors that influence the oil price adjust and reconfigure when the global dynamics change leading to larger than usual oil price fluctuations during the transition period.

The key question therefore is, with the recent oil price surge that we are witnessing post 2003, are we facing a “New Order” for oil price? The authors of this article profess that this is not a “New Order”. However, changes are occurring in the global oil business dynamics that impact the factors underlying the oil price. We are currently in a transition period (post 2003) where oil price will remain volatile as these underlying factors adjust, before settling into a new Oil Price Paradigm and an associated equilibrium oil price range.

To justify our hypothesis, let us examine in the next section what these underlying oil price factors are and how they are changing their behavior as they depart from their normal course, during the transition period.

Dynamics of the factors in the changing pardigm

Factors contributing to the oil price movement

We present the following five factors that we consider have an influence on the oil price. There are potentially other factors that may have an impact on oil price but for our discussion in this article we consider these five factors as materially significant.

- Global Demand (Population, GDP, Industrialization, Lifestyle)

- Supply – OECD Stocks (Oil Inventory)

- Spare Production Capacity

- Global Refining Capacity

- Intangibles – Geo-political and Economic Uncertainty

- Let us now discuss how each of these factors has behaved traditionally and departure from their past behavior during the post 2003 transition period.

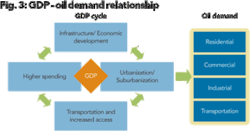

Continued global GDP growth will lead to higher energy/oil demand which subsequently will have an upward influence on oil price. Oil demand will be spurred by higher level of activities as well as lifestyle changes such as plasticization and glass packaging that require oil as an ingredient. In addition to the GDP growth and lifestyle changes, oil demand in the coming years will be greatly impacted by the nature of demand i.e., where the demand for oil is generated, OECD or non-OECD countries.

First, the rate of oil demand will be much higher in non-OECD countries in the next decade or more, as their economic growth are led by increasing commercial, industrial activities and expanding transportation networks, all of which require higher level of energy use. The need for energy will also be fueled as more and more people from these countries will want what people from richer countries have. The higher growth in oil demand is especially conspicuous with non-OECD Asian countries, particularly China and India. In 2005, non-OECD countries accounted for 1.1 Mbpd of the 1.2 Mbpd increase in oil consumption, while OECD as a whole accounted for only 0.1 Mbpd. This trend will continue over next 25 to 30 years.

null

null

Secondly, a higher need for energy to fuel their economic growth will also push non-OECD countries to protect their energy security. As a result, they will exert increasing influence in the oil supply-demand network.

Higher levels of global oil demand as well as the changing composition of countries that constitute this demand, especially the increased presence of the non-OECD countries are important characteristics of the oil supply-demand dynamics in the new Oil Price Paradigm. The oil price will trend higher due to this robust demand growth driven in great measure by rapid industrialization of non-OECD countries as well as desire to protect their energy security.

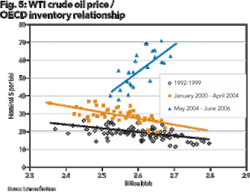

2. Supply - OECD stocks

Historically oil price has been negatively impacted by OECD stocks as increasing stock levels in OECD countries tended to place pressure on the price of crude. However reviewing the trends in Figure 5, a startling picture emerges post April 2004, as we see a departure of oil price from its historical behavior. In a complete reversal to the historical trend, price increased from $38 PBO to $70 as stocks levels simultaneously rose. This shows a willingness to not only hold but accumulate higher stocks in spite of an increasing price. Could this be the new global psychology of accepting a higher oil price? Could this be that oil companies now want to hold more inventories to react to disruptions or maximize the opportunity of futures expectation of further price rise?

In summary, price to stock correlation is showing a markedly different behavior during the transition period (post 2003) where higher oil price is being maintained even at increased oil stock levels, pointing to a new Oil Price Paradigm.

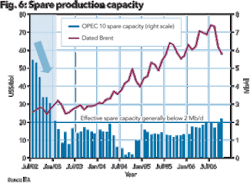

3. Spare production capacity

Spare production capacity acts as a cushion in the oil supply chain. A lower spare capacity diminishes the ability to absorb supply-demand shocks, leading to higher price.

The spare production capacity remains tight in the current years in spite of an increasing global demand for oil and higher oil prices. Investment in building additional spare capacity remains constrained due to the following reasons -

- Investment in spare capacity may result in holding idle assets that does not conform to the principles of shareholder value maximization when they will not be leveraged appropriately

- Fear that capital investment required to increase spare capacity may erode cash flow and have serious detrimental effects when price drops

- Changing geo-political dynamics leading to new political constraints hindering investment in spare capacity, e.g., tightening access to acreage by governments may limit new production capacity of IOCs

- Setting aside or building SPRs by countries (China’s intent to rapidly increase and US’s intent to double) will discourage building additional production capacities

Traditionally, most of the spare capacity that has resided in Saudi Arabia has consistently been under pressure due to filling the gap between increasing global demand and increase in non-OPEC supply as well as investment constraint as stated above. Thus while the question, “Who is going to bear the cost of additional spare production capacity” remains open, it will continue to remain very constrained in the new Oil Price Paradigm, exerting an upward influence on oil price.

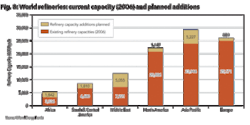

4. Global refining capacity

Refining capacity is the other big factor that coupled with spare capacity exerts a great influence on oil price.

The new geopolitical reality includes tight if not very tight collaboration between the Middle East (Mainly Saudi Arabia), China, India, and Russia. With increasing political presence, economic power and O&G technology know-how, these countries through their NOCs are collaborating to have a global impact on the worlds refining capacity. China and India are luring producing countries in West Africa and Russia into collaboration where they can provide refining capacity in exchange for stake in offshore blocks.

Countries in Middle East OPEC are also investing in new specialized refineries that can handle Heavy and Sour Crude. This will allow them to refine their own production of crude, which is mostly of the heavy and sour kind. This will expand their presence n the O&G value chain and as a result they will have greater influence on oil price. It will make them less inclined to lower price considerations while supplying their crude, as opposed to past consideration that they might have made to compete with Light and Sweet crude produced from other regions such as North Sea and parts of Africa.

In the new Oil Price Paradigm, overall global refining capacity will remain constrained as increase in investment for new refineries will be under pressure, as shown in Figure 7. In addition, as Figure 8 shows, the geographic distribution of refining capacity will change with countries in the Middle East, Asia Pacific and Africa planning to add most of the incremental refining capacity that can also handle a wide array of crude types, thus giving them a greater say in the oil price.

5. Intangibles – unforeseen events, geopolitical situation

Historically oil producing countries have shown a remarkable propensity for stable governance and economy. So much so that geo political and financial risk profile was not a strong determining factor in negotiating long term oil contracts. With the oil producing club opening its membership to more countries, this however is changing, and will become one of the more critical areas of risk in the new Oil Price Paradigm.

In a recent risk rating of about 120 countries, nearly 60% were rated lower than BBB, indicating moderate to high risk. Countries that are the most risky (CCC and D) represent a small amount of consumption but about 10% of the world’s reserves and 5% of production (~4.5Mbpd) as shown n Figure 9. Putting this in the context with the previously mentioned spare capacity constraint, one can see that these countries hold the key to the “swing” capacity. Although their share is small, a disruption in supply of 1-2 Mbpd could have sharp impact on price.

With oil production in new regions and countries around the world, we are moving into a new oil supply country network where a significant proportion of the oil supply is exposed to uncertainty/geo-economic risk. As a consequence, in the new Oil Price Paradigm we will need to reconcile with a higher “Aggregate Supply Risk and Uncertainty,” which indicates and upward influence on oil price.

The new oil price behavior outlook

A confluence of the changing behaviors of the underlying oil price factors discussed in the earlier section points to the new Oil Price Paradigm. The behavioral departure of these factors from their traditional trends and resulting volatility in the oil price defines a transition period which seems to have started late 2003/ early 2004 (Figure 2), and one that we are currently in.

Consensus and realized price variances

Further evidence to this transition period can be seen from the chart above where much larger than normal differences between realized prices (end of the year) and consensus prices (set before the beginning of the year) has occurred for two of the three years post 2003. These swings can be explained by adjustment to the new global oil business dynamics.

Emergance of a new paradigm: aggregated effect of contributing factors

The transition period marked by the green colored box in the Figure 10 below, shows the beginning of the new paradigm where the oil price equilibrium shifts from $20 - $30 range in pre-2003 era to higher oil price trend that is projected beyond 2009/10. As you might expect during the transition period we can see substantial price volatility. The earlier part of this transition shows a high upward swing in oil price reacting to initial adjustment of the underlying price factors as discussed before and a fear premium built from uncertainty and speculation associated with changing business dynamics. In the latter part, the oil world should better comprehend and settle with the new global business dynamics, thus converging to the new Oil Price Paradigm and the resulting equilibrium price range. It is important for the global community to acknowledge and reconcile with the changes as we move towards the new Oil Price Paradigm.

Conclusion

With the changes in global oil business dynamics, we are witnessing the emergence of a new Oil Price Paradigm. The underlying factors influencing the oil price which we have discussed in this article are in a transition period where they adjust to the characteristics of the new global oil business dynamics. While these adjustments occur, the transition period will be marked with larger than normal swings in the oil price. This is what we are currently witnessing since mid-year 2003. Once these underlying factors synchronize with the new global oil business dynamics, the price will settle into a new equilibrium range, as it has done in earlier time periods, such as the pre-1970 years and the period between mid-1980s to 2003 (Figure 2).

Other considerations that will influence the price of oil in the long term include, rate of global industrialization, lifestyle changes or demand containment, commercial success and rate of adoption of alternative energies, access to hydrocarbon acreage globally and, invention and successful application of new E&P technologies. OGFJ

About the authors

Adi Karev [[email protected]] is a senior partner in the Energy & Resources practice of Deloitte Consulting LLP. His clients include major global oil and gas companies. Karev’s expertise lies in facilitating solutions and troubleshooting for large strategic and transformation initiatives facing an organization’s management team. His management advisory activities have included interactions with businesses and governmental organizations across Asia, Australia, Europe, Africa, and the United States.

Manas Pattanaik [[email protected]] is a senior manager with Deloitte Consulting’s global oil and gas practice. He has 16 years’ experience in management consulting, information technology, and previously worked for Andersen Consulting, Oracle Corp., and Schlumberger. Pattanaik helps his clients design and execute business-technology strategies to improve their performance through business process transformation, technology alignment, enterprise integration, and organizational readiness.

Ashutosh Ashish [[email protected]] is a manager with Deloitte Consulting’s global oil and gas practice with more than 11 years of experience working on strategy and operations consulting and project management in the upstream sector. Currently, Ashish helps oil and gas clients improve their E&P performance by establishing business processes and standards, developing business technology strategies, and project management facilitation.