Growing need, size mismatches create dual capital challenge

Scott W. Johnson

Weisser, Johnson & Co.

Houston

The oil and gas industry is currently blessed with the greatest capital availability that we have seen in many years. Both public and private capital markets for debt and equity are relatively receptive to exploration and production companies. Yet as an industry we face a dual capital challenge. We will need even more capital in the years ahead to meet growing energy demands, especially for natural gas. In addition, there is a mismatch between the capital that is available and some of the projects and companies that require outside funding.

In most mature industries, the natural progression is toward consolidation, often resulting in a few dominant companies. In oil and gas, large company consolidation has occurred, but because the trend is toward smaller fields, small producers are constantly springing up to capitalize on their niche expertise and greater operating efficiency.

In times of high commodity prices such as we are now experiencing, larger companies are well funded with internal cash flow and have little need for outside capital. Small companies, on the other hand, are always looking for equity and debt financing for their projects. The current environment is one in which much of the need for outside capital exists within small to mid-size companies.

While the current needs for outside capital are largely with smaller companies, the size of investing institutions has increased substantially. Through the 1990s, pension funds, endowments, foundations, and various funds grew dramatically, and so did the size of the investments they prefer to make. This is one reason why companies need to be larger today to consider an initial public offering than was the case 10-15 years ago.

Most decisions about private equity, mezzanine, and project investments in oil and gas are made by knowledgeable teams managing pools of investment capital—or "funds"—for pensions, endowments, foundations, and other institutions. Many of these funds focus entirely on energy investments or more narrowly on only oil and gas, only oil service and supply, or only midstream investments.

Typically, each new fund created by one of these teams of specialists is larger than its predecessors. As the size of each successive fund grows, so does the minimum size of individual investments that it will consider. Small deals thus have become more and more difficult to finance. In terms of size, the financial world is moving in the opposite direction from much of the universe of private investment opportunities in oil and gas.

Growing needs

Current trends in US natural gas demand and production point to an extended need for accelerated resource development. Last fall's National Petroleum Council study concluded that the US will need all gas available from all sources—including LNG and an Alaskan pipeline—to meet growing demand and keep prices at $3-7/Mcf. Already, gas prices are near the upper end of that price band, and doubts are growing that LNG regasification facilities can be sited, approved, and built at the anticipated rate, given terrorist and other concerns.

Last year's drop in production indicates that the current level of about 1,200 active drilling rigs in the US will not be sufficient to overcome steep production decline rates. We need more drilling, and commodity prices appear sufficient to support more drilling. This means we need more prospects and the capital to drill them. The two must come together.

Many of the larger oil and gas companies have more cash flow than they have acceptable projects to consume it. Many are paying down debt. Some are repurchasing stock. These choices reflect more financial discipline than companies practiced in the past. There is now greater willingness to forgo aggregate volume growth in favor of higher rates of return on capital employed. If any of the large companies develop a need to raise outside capital, their options are numerous, and the cost of financing is relatively low.

By contrast, start-up companies, small producers, and private companies in general face an uncertain path to meeting their capital needs. Even in this group, some companies have access to substantial funding. Private companies managed by teams with records of profitably building and selling companies have little difficulty in reloading their balance sheets with new equity from private equity funds to pursue strategies focused on acquisition and exploitation.

Companies not fitting that mold are usually not so lucky. If their needs are less than $10 million or include significant exploration risk, they face a particularly difficult challenge.

Funding possibilities

So what funding is available to smaller companies, other than industry joint ventures? Here are some possibilities:

Banks and VPPs. Despite numerous mergers, banks remain active oil and gas lenders, and some new entrants have fortified the ranks of those making loans of less than $20 million, some even less than $10 million. Because strong industry cash flows have shrunk their aggregate outstanding loans, most banks are eager to consider new credits. But, as always, lending limits are geared primarily to existing production, typically at 50-65% of the producing reserve value plus a bit extra for nonproducing proved reserves. Therefore, for most companies the unused borrowing base will provide very limited funding for development operations. A company without substantial existing production, or with an existing bank loan that is fully utilized, will usually be held to very slow development if the only source of funding is the bank.

Volumetric production payments are likewise based predominantly on producing reserve value, though the advance rates, and the cost, are higher. These usually work best on reserves with medium to long remaining life and in a situation where there is unlikely to be any near-term need to refinance or sell the underlying assets.

Although production payment structures have been adapted to fund some development drilling, they generally do not supply adequate development capital and are not sufficiently flexible to adapt to changing circumstances. Also, most providers prefer a size of at least $20 million, and some prefer deals over $50 million.

- Mezzanine and project finance. Although the formats vary, most mezzanine loans are nonrecourse to the parent company or its management but have a first lien on specific properties, a set interest rate, and an overriding royalty that is put in place upon repayment of the loan. The focus is on financing of development drilling projects and acquisitions, generally with some amount of existing production at the outset. The total return target is in the 15-25% range, depending on the risk assessment, but often hovers around 20%.

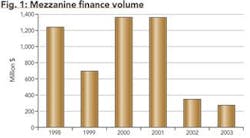

The mezzanine financing market is coming back after decimation of most providers in the financial crisis following the Enron bankruptcy, which affected integrated gas and electric companies that had marketed natural gas for producers and provided mezzanine financing together with a price hedge. These companies had been the core providers in a market that surpassed $1.3 billion/year in 2000 and 2001. By contrast, in each of the last 2 years mezzanine volume has reached only $300-400 million (Fig. 1). New participants are becoming established, and volumes are likely to rise.

The other primary form of project-based finance is project equity, which is structured as a limited partnership or limited liability company. Project equity provides high advance rates on production or development activities.

While limitations on drilling risk, well diversification, and other requirements mean that these tools will not fit some projects, mezzanine debt and project equity play an important role in funding small companies. More providers and more dollars are needed in this arena.

- Private equity. Much has been said about the abundance of private equity capital available for oil and gas today. Depending on how one defines the group, between 10 and 20 private equity funds are active investors in oil and gas. Most of these have raised new pools of capital within the last 2 years. In a number of cases, these new funds are two or three times the size of the previous fund. Because the number of investments targeted within each fund stays nearly constant, the minimum size of individual investments has risen substantially. In aggregate, there are several billion dollars of private equity capital available to be invested.

What is remarkable is how similar the investment parameters are from one fund group to the next, with few exceptions. Strong management is at the top of the checklist, particularly as evidenced by a track record of having built a company up in the past and having sold it at a large profit. Return expectations are usually at least 30%. Nearly all of these groups greatly prefer to support acquisition-and-development strategies.

After about 3 years in which it has been more difficult to purchase properties at reasonable values and to earn targeted returns with that strategy, several of these investors are now considering backing strategies that involve some meaningful amount of drilling risk. A few equity investments involving some exploration have been closed, but these remain unusual. Weisser, Johnson & Co. was recently successful in helping one such new company, Centurion Exploration, attract funding, but more success stories such as this are needed.

A few years ago, $10 million was the minimum investment size for most of the equity funds. Today it is more difficult to complete private equity investment transactions of less than $25-50 million. Needless to say, that size requirement alone is enough to exclude many companies that need funding.

Filling the gaps

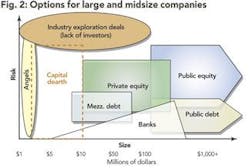

As Fig. 2 shows, there are multiple financing options for large companies and for midsized companies that can find a way to earn acceptable returns employing low risk acquisition-and-development drilling strategies.

The gaps in outside capital availability are for small companies and projects and for exploration of any sort. So we face two areas of need and opportunity.

The first is for small pools of capital, funded either by institutions or by individuals, that will invest in small companies and projects. Most of these investments can and should be oriented to lower risk drilling so that the risks of establishing a small company are not compounded by the risks of exploration. Even so, good returns can be achieved with a properly skilled investment management group since so little capital is available to this sector and the opportunities are numerous.

The second need is to find a way to fund a greater number of exploration-driven companies. Although great selectivity will be required in choosing teams and projects to back, a combination of geoscientific and financial skills should make this possible. Financial institutions are not ready to back outright wildcat drilling, but a portfolio of unproved reserve targets with probabilities of success on individual wells ranging from 30% to 70% and strong management deserves to get funded. Moves in the direction of providing small-company financing and exploration funding will be welcome steps toward addressing the capital challenge of meeting our future energy needs.

The author

Scott Johnson, a cofounder of Weisser, Johnson & Co. in 1991, has 26 years of investment banking experience including public and private financings; debt, equity, hybrid, and structured securities; corporate restructurings; and acquisitions, divestitures, and stock mergers. Following 5 years with Goldman Sachs working with companies in a variety of industries, he spent 8 years there Sachs covering oil and gas companies, oil service companies, gas distribution and electric utilities, and pipelines. Johnson holds an MBA from Stanford University and an AB from Harvard College.