Volumetric production payments in property transactions: tax rules and potential benefits

John Bradford

KPMG LLP

Houston

Morgan Holtman

KPMG LLP

Washington, DC

Production payments denominated in either dollars or volumes have long served the oil and gas industry as financing tools.1 Production payments enable oil and gas producers to monetize their proven reserves, thus providing a greater level of liquidity.

Using a volumetric production payment (VPP) in the disposition of an oil and gas producing property may provide parties to the transaction with advantages in certain circumstances.

This article examines the tax rules surrounding production payments and the possible benefits of using a VPP in oil and gas producing property transactions.

Production payments

In a dollar-denominated production payment, the holder provides the producer with an up-front cash payment and in return receives periodic cash payments based on production until the principal and interest specified in the production payment agreement are satisfied. Because principal and interest are payable solely from production obtained from designated fields, reserve risk and production risk are shifted to the holder of the production payment. Price risk on the oil and gas commodity remains with the producer, however, as lower commodity prices mean more production will be needed to satisfy the principal and interest obligations. For accounting purposes, a dollar-denominated production payment is generally considered a borrowing.

In a VPP, the holder provides the producer with an up-front cash payment and in return receives specified amounts of oil and gas delivered from designated fields over specified periods of time. In most producing states, the producer executes an agreement conveying the specified reserves to the holder, and the holder records the conveyance in the real property records of the local jurisdictions in which the fields are located.

As with the dollar-denominated production payment, in a VPP reserve risk and production risk shift to the holder because the holder looks solely to the designated fields for the production to which it is entitled. Commodity price risk also shifts from the producer to the holder because the holder takes as payment the commodity in kind.

Because the interest rate implied in the valuation of a VPP is not fixed, the holder also assumes interest rate risk. Before the growth of the commodities and interest rate derivatives markets, those risks inherent in a VPP were reflected in its financial pricing. This tended to make VPPs more expensive than dollar-denominated production payments.

Today, holders of VPPs can mitigate price risk on the to-be-delivered volumes by selling those volumes forward in the commodity markets as soon as the VPP is executed. Holders can also mitigate interest rate risk with interest rate derivatives. The ability to mitigate those risks has helped to make the financial pricing of VPPs more competitive. Moreover, for accounting purposes, the VPP is generally not considered a borrowing.

Creative solution

A VPP can be a creative solution to economic, accounting, and tax issues associated with oil and gas producing property disposition transactions. Consider the following example:

Production Co. wishes to sell $500 million worth of oil and gas producing properties that it operates. The properties include both proved developed producing (PDP) and proved undeveloped (PUD) reserves.

The potential purchaser, Buyer Co., wishes to operate the properties and develop the PUD reserves but is unwilling to pay Production Co.'s asking price for the PDP reserves (which is based on the estimated forward price curves for crude oil and natural gas for the estimated life of the PDP reserves).

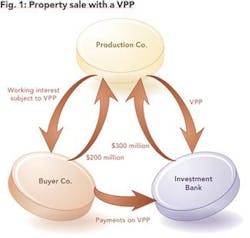

In order to consummate the sale to Buyer Co., Production Co. conveys a 5-year VPP carved out of a substantial portion of the PDP reserves to Investment Bank for $300 million. The carved-out VPP covers approximately 80% of the PDP fair value, with the price per barrel-equivalent based on the forward price curve. Production Co. then sells the oil and gas properties subject to the carved-out VPP to Buyer Co. for $200 million, with the price per barrel of oil-equivalent based on Buyer Co.'s offer price (see figure).

By structuring the transaction in a manner that results in the sale of most of the less risky PDPs to a financial investor, Production Co. received a higher overall average price per barrel of oil-equivalent than it would have received had it sold the properties to Buyer Co. without a VPP. Futhermore, Buyer Co. acquired the properties and rights it valued (the PUD reserves and operating rights) at the price it desired. And Investment Bank profited from the VPP by locking in the commodity price and interest risks with financial derivatives.

Tax definitions

For federal income tax purposes, a production payment is a right to a specified share of the production from oil and gas in place (if, as, and when produced) or the proceeds therefrom.2 The holder of the production payment is entitled to the specified volumes free and clear of the costs of operating the oil and gas property.3

Treasury Regulation Sec. 1.636-3(a)(1) further defines a production payment for federal income tax purposes by requiring the following criteria to be satisfied:

1. The right must be an economic interest in the minerals in place (a taxpayer holds an economic interest if it acquires by investment any interest in mineral in place and secures, by any form of legal relationship, income derived from the extraction of the mineral, to which income the taxpayer looks for a return of capital).4

2. It must be limited to a specific dollar amount, quantity of mineral, or period of time.

3. Its expected economic life, at the time the right is created, must be of shorter duration than the expected economic life of the burdened property.5

If the production payment can be satisfied by other than production, it is not an economic interest.6 A production payment can burden more than one mineral property.7 A right to oil and gas reserves in place has an economic life of shorter duration than the economic life of the oil and gas property burdened by the production payment only if the right is not reasonably expected to extend in substantial amounts over the entire productive life of the burdened property.8 Under the regulations, any right that is, in substance, economically equivalent to a production payment (for example, a limited-term royalty interest) is treated as a production payment under Sec. 636.9

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) should issue a ruling that a right constitutes a production payment if:

1. The right is an economic interest under Regulation Sec. 1.611-1(b).

2. The right is limited to a specified dollar amount, quantity of mineral, or period of time.

3. It is reasonably expected that, at the time the right is created, the right will terminate upon the production of not more than 90% of the minerals then known to exist in the burdened mineral property.

4. The present value of the production expected to remain after the right terminates, determined at the time the right is created, is 5% or more of the present value of the burdened mineral property.10

Tax treatment

As a general rule, under Sec. 636(a), a production payment carved out of mineral property by a producer (a carved-out production payment) is treated as a mortgage loan on the property.11 The producer recognizes no income or gain on receipt of the production payment proceeds but instead recognizes income, subject to depletion, as the oil and gas that satisfy the production payment are produced and sold.

A production payment created and retained on the complete transfer of the mineral property burdened by the production payment (a retained production payment) is treated under Sec. 636(b) as a purchase-money mortgage on the burdened mineral property.14 The seller generally includes the value of the production payment in its amount realized for purposes of computing gain or loss on the sale of the burdened property.15 The buyer of the property will acquire basis in the property for the production payment amount only as the production payments are made.16

A production payment retained by a lessor or sublessor in a leasing transaction is treated by the lessor as ordinary income subject to depletion and by the lessee as lease bonus payable (and added to basis) in installments.17

Possible benefits

VPPs offer a range of potential benefits to both sellers and buyers in transactions involving oil and gas properties.

For sellers

One way a seller of an oil and gas producing property might achieve its target selling price would be to retain a VPP in the sale of the properties and collect future cash payments based on the delivered production. But the sale of oil and gas producing property subject to a retained production payment has certain economic, tax, and accounting consequences.

For example, the seller would receive a reduced amount of initial cash proceeds and would remain exposed to future production risk on the properties. For financial reporting purposes, a seller using the successful efforts method of accounting would recognize gain or loss, if any, on the sale only with respect to the reserves attributable to the property transferred.18 For tax purposes, the seller would include the fair market value of the retained VPP in its amount realized on the sale. It therefore would have a tax liability determined with regard to the full value of the property sold, even though the seller received initial cash proceeds only attributable to the reserves transferred to the buyer.19

However, if the seller carved out and sold a VPP to a third party for cash prior to selling the underlying properties, the seller might achieve different economic, tax, and accounting results. More specifically, the seller in that context may:

- Initially realize the full cash value of the oil and gas properties sold.

- For financial reporting purposes, and assuming the seller uses the successful efforts method of accounting, recognize gain or loss, if any, on the sale with respect to the reserves attributable to the property transferred and those attributable to the VPP.

- For tax purposes, increase cash available to pay the tax attributable to the sale.

For buyers

With the VPP in place prior to the acquisition, the buyer might take the position for financial reporting purposes of recording only the asset it purchased: the reserves attributable to the burdened working interest. The buyer similarly might take the position that the PDP reserves used to fund the VPP payments to the holder and the VPP obligation should not be recorded for financial reporting purposes.

For federal income tax purposes, the buyer should achieve a basis in the properties that includes the cash paid and the financing assumed.20 If the buyer had instead purchased the oil and gas property subject to a VPP retained by the seller, the buyer would have basis in the property attributable to the VPP that accrues over time.21

Other benefits

In addition to the accounting and tax treatment that parties to a conveyance might receive when using a VPP, a seller may be able to increase the number of potential buyers by burdening significantly valued producing properties with a VPP prior to the sale. That is, by lowering the cash purchase price with the VPP, more companies will be in a position to competitively bid for the properties.22 An additional benefit to the buyer in this scenario is the potential to earn operator's fees on a much larger pool of properties than it otherwise could have afforded to purchase.

As detailed in this article, the VPP may provide certain advantages to some companies given the right set of circumstances. Buyers and sellers should carefully analyze all the elements of their disposition transactions when deciding whether or not to use a VPP and should always consult with their tax and accounting professionals before making a decision. ogfj

References

1. As explained in more detail below, a production payment is a right to a specified share of the production (or the proceeds therefrom) from an oil and gas property. The right to the specified share may be limited to a specified dollar amount, quantity of mineral, or period of time. A dollar-denominated production payment is a production payment limited to a specified dollar amount, payable periodically in cash. A volumetric production payment is a production payment limited to a specified quantity of mineral and payable in kind.

2. Treasury Regulation Sec. 1.636-3(a)(1). See also Financial Accounting Standards Board Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 19 (FASB 19), Secs. 43(b), 47(a).

3. See FASB 19, Sec. 47(a).4. .Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.611-1(b)(1).

5. See United States vs. Morgan, 321 F.2d 781 (5th Cir. 1963), on remand at 245 F. Supp. 388 (S.D. Miss. 1964).

6. See Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.636-3(a)(1).

7. Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.636-3(a)(1).

8. Ibid.

9. Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.636-3(a)(2).

10. See Rev. Proc. 97-55, 1997-2 CB 582.

11. See Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.636-1(a)(1)(i). Although Sec. 1.636-3(a)(1) requires that a VPP constitute an economic interest, a production payment to which Sec. 636(a) applies is not treated as an economic interest for purposes of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). See IRC Sec. 636(a); Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.636-1(a)(1)(i). A production payment carved out of mineral property for exploration and development of the mineral property is generally not treated as a mortgage loan. See IRC Sec. 636(a).

12. See Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.636-1(a)(1)(ii).

13. Ibid. As a general matter, production payments are treated as contingent payment debt instruments (CPDIs) under Sec. 1275(d) and Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.1275-4. Reg. Sec. 1.1275-4 provides rules for determining the amount of each production payment that would be treated as payment of interest and principal and, correspondingly, the amount of interest income and expense that would be recognized by the parties and the amount of basis, if any, that would be recovered by the holder of the production payment as return of principal.

14. IRC Sec. 636(b); Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.636-1(a)(1)(i).

15. Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.636-1(c)(1)(i). The seller may be permitted to recognize gain on the sale of the property under the installment sale method provided the transaction otherwise qualifies for the installment sale method. See Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.636-1(c)(4). Sec. 1245 recapture income would not qualify for installment sale treatment, however. See IRC Sec. 453(i).

16. Treas. Reg. Secs. 1.1274-2(g), 1.1275-4(c)(7), Example 1 (iv). A retained production payment should be treated as a wholly contingent CPDI issued for nonpublicly traded property and having an initial issue price of zero. As production payments are made, principal and interest payments are determined, and the principal payments are added to the buyer's basis in the property.

17. IRC Sec. 636(c); Treas. Reg. Secs. 1.636-2(b) (describing the tax treatment of a VPP by the lessor)-2(a) (describing the tax treatment of a VPP by the lessee).

18. See FASB 19, Secs. 47(m), 47(k), 47(i). Sellers on the full cost method generally do not recognize gain or loss on the disposition of oil and gas properties. See Ibid; Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Reg. S-X, 17 CFR Sec. 210.4-10(c)(6)(i).

19. The seller may be able to recognize a portion of the tax gain on the sale under the installment method. See No. 15 above.

20. Under Reg. Sec. 1.1274-5(d), a buyer's basis in property that is purchased subject to indebtedness equals the sum of the cash paid and the adjusted issue price of the debt instrument as of the date of the purchase. The issue price of a debt instrument issued for money, as in the case of a carved-out VPP, is the amount of cash paid for the instrument. See Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.1273-2(a)(1). Under Reg. Sec. 1.1275-1(b)(1), an instrument's "adjusted issue price" is its issue price (1) increased by the amount of original issue discount previously included in the holder's income, and (2) decreased by the amount of payments previously made on the instrument (other than payments of qualified stated interest). Original issue discount on the VPP included in income by the holder of the production payment would be viewed as paid by the buyer of the property as each payment on the production payment is made. In that case, the net adjustment to the issue price of the VPP would be zero. As an alternative, the buyer could achieve the same basis in the property as in the carved out production payment scenario while making a relatively smaller cash outlay by paying the full sales price for the properties initially and then selling a production payment for cash to a financial institution. In that context, however, the buyer would not receive the book treatment associated with purchases of property subject to carved-out production payments.

21. In that case, the issue price of the VPP obligation initially would have been zero since it would be treated as a wholly contingent CPDI issued for nonpublicly traded property. See Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.1274-2(g). Basis would accrue over time as payments were made on the production payment. See Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.1275-4(c)(7), Example 1 (iv).

22. This is sometimes referred to as seller-arranged financing.

The authors

John Bradford is partner, passthroughs, in the Washington National Tax Group of KPMG LLP. He joined KPMG in 2002 after leading JPMorgan's structured capital practice for energy clients. Earlier, he worked for 18 years at Exxon Corp., where he became senior tax counsel. A member of the American Bar Association, Bradford holds degrees in accountancy and law from the University of Illinois and a master of laws in taxation degree from the University of Houston.

Morgan Holtman is a manager in the passthroughs practice of KPMG LLP's Washington National Tax Group, which she joined in 2001. She holds an LLM degree from Georgetown University, a JD from Widener University (Delaware) School of Law, and a BA from the University of Delaware.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of KPMG LLP, the US member firm of KPMG International.